The relationship between poetry forms and language cannot be overstated: with different forms of poetry, poets encounter new ways to grapple with complex poetic topics. Indeed, poets have played with form since the dawn of poetry, resulting in the countless forms of poetry that us poets have at our disposal. Understanding most forms is easy, but if you plan on mastering poetry forms and poem structures, you need to know your poetic history.

This article covers everything a poet should know about rhyme schemes, different types of poetry forms, and identifying poetic meter. After exploring these components, we explore 15 forms of poetry, with tips and examples for poetry writers.

Let’s learn what the masters know about poetry forms. Then we’ll look at 15 poetry forms to experiment with in your own poetry writing.

Contents

What Are Poetic Forms?

A poem’s form is its structure: elements like its line lengths and meters, stanza lengths, rhyme schemes (if any) and systems of repetition.

A poem’s form refers to its structure: elements like its line lengths and meters, stanza lengths, rhyme schemes (if any) and systems of repetition. Every poem has a form—its own way of approaching these elements—whether that form is unique just to that poem, or part of a more widely used poetic form.

Poetry forms are defined poetic structures used across multiple poems, generally by multiple authors. Two well-known examples are the haiku and the limerick.

That brings us to poetry forms: defined poetic structures used across multiple poems and generally by multiple authors. Two well-known poetry forms are the haiku and the limerick. Both forms of poetry are defined by their structure in exactly the elements described above: line length, meter, rhyme scheme. And these forms influence how the poetry written in them tends to turn out, from terse and profound (haiku) to singsongy and silly (limerick).

All defined forms of poetry share three elements:

- Intentional line breaks and stanza breaks

- Consistent rhyme scheme

- Adherence to the rules of meter in poetry

Let’s investigate each component of poem structures individually, before turning our gaze towards 15 example forms of poetry.

Article continues below…

Formal Poetry Writing Courses We Think You'll Love

We've hand-picked these courses to help you flourish as a writer.

Crafting Poems in Form: Rhyme, Meter, Fixed Forms, and More

Working within the guidelines of a fixed poetic structure can make your poetry more creative, not less. Find freedom in...

Find Out More

Sound, Form, and Image: An Intermediate Poetry Workshop

Write more powerful poetry though sound, form, and image. Explore poetic craft and creativity to write your most imaginative and...

Find Out MoreOr click below to view all courses.

See CoursesArticle continues…

Poetic Forms: Lineation in Poetry

Lineation refers to the line breaks and stanzas that architect a poem.

Lineation refers to the line breaks and stanzas that architect a poem. The length of these lines and stanzas greatly impacts how the reader interprets the poem, so a poem’s lineation requires painstaking care.

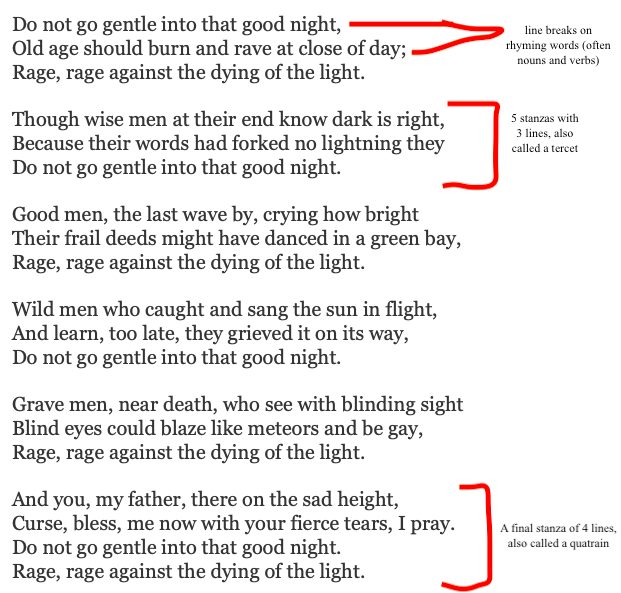

Some poetry forms and structures allow the poet to choose their own line and stanza lengths; others, like the ghazal or the sestina, have stricter requirements. Another poetry form with strict requirements is the villanelle, such as the poem “Do not go gentle into that good night” by Dylan Thomas:

You’ll notice that stanzas of different length have different names. The chart below includes the common names for stanzas of varying length.

| Number of Lines | Stanza Term | Suggested uses |

| 1 | Line | Emphasizes standalone lines. |

| 2 | Couplet | Builds tension through juxtaposition and contrast |

| 3 | Tercet | Storytelling, embedding meaning, juxtaposition |

| 4 | Quatrain | Popular in many poetry forms |

| 5 | Quintain | Juxtaposing many different images, like in a cinquain |

| 6 | Sestet | Exploring complex problems, as in many sonnets |

| 7 (rare) | Septet | Free verse/isometric poems |

| 8 | Octet | Exploring complex problems, as in many sonnets |

| 9 (rare) | Nonet | Free verse/isometric poems |

| 10 (rare) | Dizain | Free verse/isometric poems |

Note: A single-line stanza is sometimes called a “monostich,” though this typically refers to a one-line poem. Since a stanza consists of multiple lines, it’s best to call a single-lined stanza a line itself.

You’ll notice that several of the stanza lengths are rare. Why is that? Few, if any, forms of poetry require the use of septets, nonets, and dizains. You may see stanzas of this length in free form poetry, but you will rarely see those terms outside of this article, given how infrequently they’re used.

Why use stanzas at all? Think of the stanzas as the paragraph of the poem. A stanza can hold singular ideas that contrast with other stanzas, or a stanza can hold multiple conflicting ideas that build tension within the poem. Stanzas help the poet with juxtaposition, repetition, and other poetic devices. For more on this, review our article on reading poetry like a poet.

As a parting note on stanza length, a poem without stanzas is called an isometric poem. Isometric poetry is just as valid as poems with stanzas, and the isometric form helps poets unify individual lines into an overarching theme. Contemporary sonnets are often isometric, as are some free verse poems.

Poetic Forms: Rhyme in Poetry

For most of poetry’s existence, rhyme schemes have been a critical component of the poem’s construction. Formally, rhyme is when two words agree in terminal sound, like “light” and “night.” Most of us can feel when two words rhyme, so it’s best not to overthink.

Rhyme is when two words agree in terminal sound, like “light” and “night.”

Yet, contemporary poetry seems to snub the rhyme scheme. You’ll rarely see rhyming in some modern poetry journals, except maybe internal rhyming—a topic we’ll cover later in this article.

Why did society suddenly switch to non-rhyming poetry? Are rhyme schemes even important these days? Rhyme and meter developed out of necessity—not for “literary” purposes, but mnemonic purposes. Poetry predates writing; we’ve been telling stories in poetry long before we had prose as a medium. Rhyme schemes allowed early poets to retell their poetry orally, which is why rhyme schemes endure into the modern era.

Rhyme schemes allowed early poets to retell their poetry orally.

In fact, rhyme continued to define poetry until the turn of the 20th century. By then, literacy rates among Western nations had dramatically improved, and poets didn’t need oral performance to spread their poetry—books were the new poetic medium. The new challenge for poetry was to find poetic meaning in the space of the page, rather than the space of the stage; thus, rhyme schemes fell out of favor throughout the 20th century and into the 21st.

So, what is form in poetry for today’s poets as it pertains to rhyme? Should contemporary poetry refrain from rhyme? Well, not all the time. Many contemporary poetry forms still require a rhyme scheme, such as the villanelle, the limerick, and some sonnets.

Many contemporary poetry forms require a rhyme scheme, such as the villanelle, the limerick, and some sonnets.

Poets talk about rhyme the same way musicians do. Let’s say we have four lines, and each line ends with the same rhyme; we would describe that rhyme scheme as AAAA. If we had four lines with two alternating rhymes, we would describe it as ABAB. If the middle lines and the outer lines rhymed with each other, we would have ABBA. Pretty simple, right?

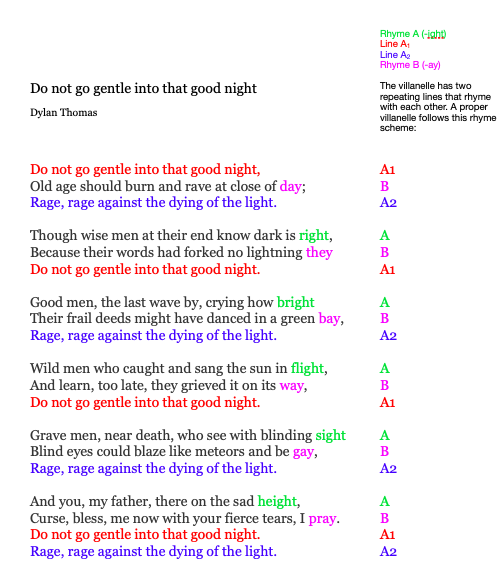

Let’s see rhyme in action before we move towards poetic meter. The villanelle poetry form, which we will later explore in-depth, has a fairly tricky rhyme scheme. For the sake of consistency, we’ll return to Dylan Thomas’ “Do not go gentle into that good night,” with the villanelle form explained in the margins.

Poetic Forms: Meter in Poetry

Meter refers to the way certain sounds are emphasized in a poem. In short, every syllable we speak is either stressed or unstressed. Take the word “poem”: the first syllable, “po”, escapes the mouth with emphasis, whereas the second syllable, “em”, escapes the mouth rather quickly. In other words, “poem” is “stressed-unstressed” (a trochee).

Like rhyme, meter evolved as a mnemonic device. If the speaker can remember how the words are spoken, they can remember the words themselves simply by falling into the poem’s rhythm.

While meter is less emphasized in contemporary poetry forms, many of the best-known poetry forms, like the sonnet, have well-defined meters.

Also like rhyme, meter is less emphasized in contemporary poetry. Even contemporary forms of poetry rarely have specific metrical requirements. However, many of the best-known poetry forms, like the sonnet, have well-defined meters.

Part of the reason for this change is because language, especially the English language, has become much more global—and, as a result, much more varied in its pronunciations.

For example, I write to you with a Midwestern American accent. There, “poem” is pronounced with two syllables. However, an English speaker in Northern Ireland might pronounce “poem” as one stressed syllable—sounding more like “pome.” Both pronunciations are valid, yet both make it harder for a metrically correct poem to succeed on the other side of the Atlantic.

Simply put, meter isn’t always a huge concern for contemporary poets. Nowadays, poetry searches for euphony by combining different sound elements like alliteration, repetition, internal rhyme, and onomatopoeia.

If you’re reading classics, then it helps to know about the types of meter in poetry and how meter can influence the poet’s word choice. We’ll cover it briefly. Note that the following information applies best to European poetry; metrical rules vary by culture, a notable example being Vedic poetry, but that’s a topic for a different article.

Poetry meter considers two things: the pattern of syllable stresses and the length of the line.

Syllabic Stress

We mentioned earlier how words can have stressed and unstressed syllables. When these syllables are arranged into certain repeating patterns, different forms of poetry emerge.

One of the most common meters is the iambic meter. In other words, the poet writes the poem in a series of iambs—groupings of unstressed–stressed syllables. Take the following words for example:

- Above

- Arise

- Diverge

- Embrace

- Exist

- Predict

The italicized portions are the stressed syllables. Of course, you don’t need to use only iambic words in an iambic poem, you just need to fit the pattern. Take Emily Dickenson’s poem “The Only News I Know”:

Is bulletins all day

From Immortality.The Only Shows I see—

Tomorrow and Today—

Perchance Eternity—

Many forms of poetry use iambic meter, in part because it replicates the beat of one’s heart (ba-dum, ba-dum, ba-dum). But, while iambs are a common poetic meter, you should know a few others that classical poets used.

| Meter | Pattern | Example |

| Iamb | Unstressed–stressed | Exist |

| Trochee | Stressed–unstressed | Sample |

| Pyrrh | Equally unstressed | Pyrrhic |

| Spondee | Equally stressed | Cupcake |

| Dactyl | Stressed–unstressed–unstressed | Freshener |

| Anapest | Unstressed–unstressed–stressed | Comprehend |

| Amphibrach (rare) | Unstressed–stressed–unstressed | Flamingo |

Line Length

In classical poetry, every line has the same number of feet. A foot, in this case, refers to the patterns of syllabic stress. So, an iamb counts as one foot, as well as an anapest or a dactyl. Whichever type of foot the poet chooses, they must write the entire poem in that meter, and each line must have the same amount of feet.

So, if you’re like Shakespeare, you write your sonnets in “iambic pentameter.” In other words, each line has 5 (penta) iambs. Or, if you’re like the poet Philip Larkin, you may have written in trochaic tetrameter—lines with 4 (tetra) trochees each.

The chart below offers the formal name for a line with X amount of feet.

| Number of feet | Metrical name |

| 1 | monometer |

| 2 | dimeter |

| 3 | trimeter |

| 4 | tetrameter |

| 5 | pentameter |

| 6 | hexameter |

| 7 | septameter |

| 8 | octameter |

| 9 | nonameter |

| 10 | decameter |

Learn more about meter here:

15 Forms of Poetry

Now that we’ve covered the basics of poetry forms and poem structure, it’s time to dive into the forms themselves. Each of these poetry forms have interesting histories, tricky requirements, and many examples in both classical and contemporary poetry.

Keeping these forms of poetry in your toolkit can help you approach the poetic craft in new and exciting ways, so try your hand at as many of these poetry forms as you can.

Types of Poetry: The Ghazal

Length: Minimum of 10 lines

Stanzas: Couplets

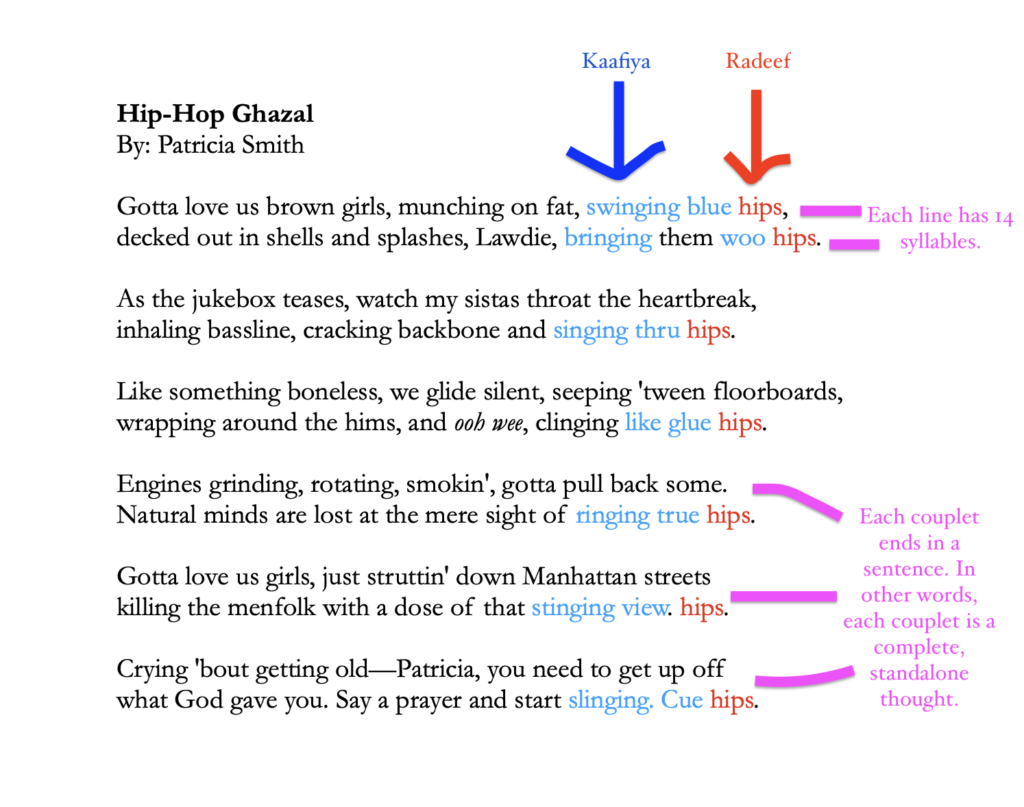

Metrical requirements: All lines must have the same number of syllables.

Rhyme Scheme: Both lines of the first couplet end with the same word. This word also ends line 4, 6, 8, etc. The word preceding the repeating word follows a different rhyme scheme.

The ghazal (pronounced like “guzzle”) has a long and complex history, migrating throughout Africa, Asia, and the Middle East in its 1400 year history. The earliest ghazals date back to 7th century Arabia, shortly after the Islamic Caliphate was formed. Ghazals are romantic and tragic in nature, a tradition which many contemporary poets uphold.

The ghazal’s form and function varies somewhat between cultures, but the general rules for writing a ghazal are the following:

- Every line must have the same number of syllables. Your choice!

- Each stanza must be a couplet.

- There must be a minimum of 5 couplets.

- The first and second line of the poem end with the same word, called the radeef.

- Even numbered lines (Lines 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, etc.) also end with the radeef.

- The word before the radeef must also rhyme. It cannot rhyme with the radeef, and the same word cannot be used twice. This word is called the kaafiya.

- Each couplet must operate independently and as a whole. The couplet can stand alone as a poem, and it can form a larger poem, much like pearls on a string forming a necklace.

Psh, is that all? Ghazals are tricky and require each word to be carefully chosen, so a good ghazal may take a very long time to complete. Here’s a ghazal example, with notes demonstrating the above requirements.

Other contemporary ghazals:

With Prayer by Zeina Hashem Beck

“Ghazal of the Better-Unbegun” by Heather McHugh

Learn more about writing the ghazal here:

Types of Poetry: The Sestina

Length: 39 Lines

Stanzas: 6 sestets and 1 tercet

Metrical requirements: None

Rhyme scheme: None. Rather, emphasis is placed on the last words of each line, which are repeated throughout the poem and then reused to form the final tercet. Yes, it’s tricky.

The sestina form hails from Italy, and the earliest known sestina was written at the turn of the 13th century. As most things do, the sestina changed slightly when it was reintroduced to American poets; nonetheless, this relatively unchanged poetry form remains a headache to write for poets everywhere.

The sestina is composed of 6 sestets, as well as a final 3 line envoi (concluding stanza). (Note: this envoi is optional, and some sestinas eschew it.) In a sestina, special attention is placed on the last word in each line. These words are repeated throughout the poem in a special pattern, essentially forming the poem’s backbone.

The last word of each line follows this order:

Stanza 1: ABCDEF

Stanza 2: FAEBDC

Stanza 3: CFDABE

Stanza 4: ECBFAD

Stanza 5: DEACFB

Stanza 6: BDFECA

Stanza 7: (B)E(D)C(A)F

Alternate Stanza 7: (A)B(C)D(E)F

This is much easier to understand when you see it color-coded. See below, using the sestina “Homes” by early Feminist Charlotte Anna Perkins Gillman.

Other contemporary sestinas:

Farm Implements and Rutabagas in a Landscape by John Ashbery

A sestina for a black girl who does not know how to braid hair by Raych Jackson

Paysage Moralisé by W. H. Auden

Learn more about the sestina here:

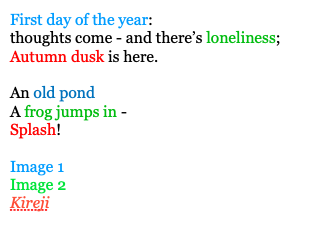

Types of Poetry: The Haiku

Length: 17 syllables divided into 3 lines, following the pattern 5-7-5.

Stanzas: One tercet

Metrical requirements: None

Rhyme scheme: None

The haiku hails from Japan, though a lot has been lost-in-translation between Japanese haikus and English-language haikus. Originally, the haiku was the opening stanza to a renga—a collaborative work of poetry common in the Japanese tradition. By the 17th century, poets published haikus as standalone pieces, and a new poetic tradition developed.

Despite its brevity, the traditional haiku form has a bit of complexity. These simple 17-syllable poems often juxtapose opposing ideas or images, centered around a kireji, or “cutting word.”

Below are some rough translations of haiku by Basho.

You’ll notice that there’s a lot of flexibility in where the images and the kireji are placed. What matters for the haikuist is to place two images against each other, then place those images in relation to the kireji. Complex ideas can be introduced from the simple nudge of a haiku.

English language haikus often lack the aforementioned complexity. Some haiku writers still subscribe to the 5-7-5 rule, but just as many have eschewed syllable rules entirely. The American Academy of Poets defines the modern haiku as a short poem that “focuses on one brief moment in time, employs provocative, colorful imagery, and provides a sudden moment of illumination.”

Below are some examples of contemporary haikus that accomplish complexity, while still adhering to the 5-7-5 rule.

Small Poems for Big by Chinaka Hodge

Haiku [for you] by Sonia Sanchez

Types of Poetry: The Tanka

Length: 31 syllables divided into 5 lines, following the pattern 5-7-5-7-7

Stanzas: 1 quintain

Metrical requirements: None

Rhyme scheme: None

Many Western writers erroneously compare the tanka to the haiku. Yes, their syllable requirements are similar: the haiku’s 17 syllables are written 5-7-5, and the tanka’s 31 syllables are written 5-7-5-7-7.

Despite this, the two poems have different histories and terminologies. The earliest tanka were written in the 7th century, and the form evolved as a short, romantic poem often shared between lovers. In both content and construction, the tanka shares many similarities to the sonnet: both often dwell on love, and both rely on a sudden or unexpected turn in language.

A tanka has three parts: the top image (kami-no-ku), the bridge (engo), and the bottom image (shimo-no-ku). This bridge varies from the kireji in haiku: where kireji should be a single cutting word, the bridge in a tanka can use multiple words, but it must connect the tanka’s images in a surprising way.

Few poets today write tanka, so it’s harder to find good contemporary pieces. However, Tanka by Sadakichi Hartmann provides great examples of brevity and wit, and you can also find copious pieces at the archive of American Tanka.

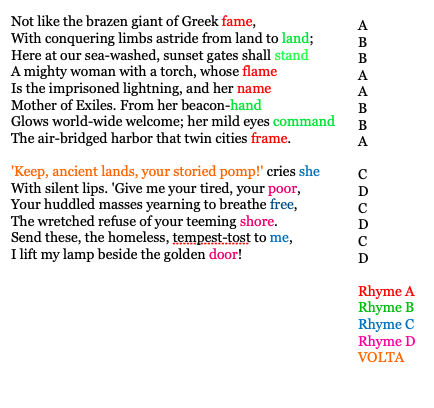

Types of Poetry: The Italian Sonnet

Length: 14 lines

Stanzas: 2 stanzas, an octet and a sestet

Metrical requirements: Iambic Pentameter

Rhyme scheme: ABBA ABBA CDE CDE. Some variation exists for the rhyme scheme of the last six lines, but the first eight lines are always ABBA.

There are three major types of sonnets: Italian, Elizabethan, and Contemporary. Moving chronologically, we’ll start with the Italian Sonnet.

Italian Sonnets originate in the 13th century, but poets weren’t captivated by the sonnet until Petrarch. Francisco Petrarca, contemporarily known as Petrarch, was a 14th century sonneteer whose dedication to form promulgated the first sonnet tradition.

This tradition requires the following:

- An opening octet which introduces the poem’s core problem. The poet must express a question, argument, moral quandary, or other such issue.

- A closing sestet which responds to the octet and offers a resolution.

- A volta at the beginning of the sestet (line 9). The volta should be a sudden change in the poem’s tone, images, and/or style.

- Strict adherence to iambic pentameter.

To see these traditions in action, look no further than the poem “The New Colossus” by Emma Lazarus. This poem, found at the base of the Statue of Liberty, is highlighted for your convenience below.

Contemporary poets don’t write this poetry form too often, as the Elizabethan Sonnet proved much more popular throughout history. More Italian Sonnets can be read here:

London, 1802 by William Wordsworth

Sonnet 43 by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

The Grave of Keats by Oscar Wilde

Types of Poetry: The Elizabethan Sonnet

Length: 14 lines

Stanzas: Either isometric OR 3 quatrains and a couplet

Metrical requirements: iambic pentameter

Rhyme scheme: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG

The Italian Sonnet hasn’t changed much in Italy, but when Englishmen started writing sonnets, the form evolved into something new and exciting. Also known as the Shakespearean Sonnet, Elizabethan Sonnets entered poetic history in the 16th century, then grew in popularity under the reign of Elizabeth I. Shakespeare commandeered the sonnet for most of his plays, owing to the form’s continued appreciation.

Like the Italian Sonnet, Elizabethan Sonnets have 14 lines in iambic pentameter. These lines include a core issue, a 9th line volta, and a poetic resolution. Additionally, the final two lines of the sonnet often comment on the first 12 lines.

Elizabethan Sonnets are just as tricky to write as Italian Sonnets, but poets often prefer the Elizabethan because of its Shakespearean history. Many poets of antiquity would compose strings of Shakespearean Sonnets that built off of one another, creating entire stories out of iambic pentameter.

For contemporary poets, the only difference between these two sonnets is the rhyme scheme. You can see this rhyme scheme in action here:

Sonnet 18 by William Shakespeare

Fancy in Nubibus by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Types of Poetry: The Contemporary Sonnet

Length: 14 lines

Stanzas: variable

Metrical requirements: variable

Rhyme scheme: variable

Sonnets created a lot of history between Shakespeare’s time and ours. For the purposes of brevity, let’s move towards modern sonnets, as there are countless classical sonnet forms that aren’t worth getting sucked into.

You might remember that rhyme schemes fell out of favor with poets in the 20th century; the sonnet was no different. Contemporary sonnets have less rules and more flexibility, and today’s poets have certainly risen to that challenge.

Today, a sonnet doesn’t have the same strict requirements. There are no metrical requirements, so the sonnet’s tradition of iambic pentameter is optional. Rhyme schemes and stanza breaks also vary, and the volta now rests between the 7th and 9th line.

Rather than force certain rules of rhyme and meter, the contemporary sonnet asks the poet to use form as a vehicle for meaning. Terrance Hayes takes this task rather literally: his American Sonnets tread our modern political landscape, using language to create form rather than using form to create language.

Other great contemporary sonnets include:

Types of Poetry: The Limerick

Length: 5 lines

Stanzas: 1 quintain

Metrical requirements: A form of anapestic trimeter

Rhyme scheme: AABBA

acting like a poetic wingman.

It was stolid and stout

and raucous throughout

though deep meaning was rarely to be had.

How is that for a short poem? The limerick was invented in England during the 19th century. What began as a silly form of poetry quickly turned into a quippy poetic ode, as the limerick became a fun and humorous way to write about other people.

The limerick has some strict requirements, but they’re a pleasure to write nonetheless. It has five lines following the rhyme scheme AABBA. A lines are usually longer and B lines are usually shorter—you’ll notice this in the example I wrote. You might also notice a certain rhythm to the words. Generally, the A lines are 8-10 syllables and the B lines are 5-7, though this is mostly a recommendation to fit the poem’s lightheartedness. Limericks also follow a modified form of anapestic trimeter. It’s easy to hear that meter in play at these readings (start at 2:00).

Limericks usually talk about people, though of course, poets have hijacked it to talk about other things. Nonetheless, you can find wondrous and pithy poetry in the following limericks.

Limericks by Edward Lear (the creator of the Limerick)

A Young Lady of Lynn (anonymous)

There Was a Small Boy of Quebec by Rudyard Kipling

Types of Poetry: The Villanelle

Length: 19 lines

Stanzas: 5 tercets and a quatrain

Metrical requirements: none

Rhyme scheme: Too complicated to summarize

So, which one of you is the poet who hates sestinas, and which one of you is the poet who hates villanelles?

Oddly enough, the villanelle didn’t begin as a complicated form. Throughout the Renaissance, villanelles were simple rustic poems designed to appreciate the idyllic country life. It wasn’t until the villanelle rose in popularity among English poets that the form gained complexity, resulting in the rather complicated rhyme scheme we see today.

A villanelle is composed of two rhyming refrains (repeating lines). These refrains interweave throughout the rest of the poem, forming the skeleton of the poem’s rhyme and subject matter. As a general rule, it’s best to start a villanelle by figuring out the refrains, as most villanelles get remembered for these through-lines.

The 4 components of a villanelle are best summarized below:

- A1: Refrain 1

- A2: Refrain 2

- A: Non-refrain rhyme beginning most stanzas

- B: Alternate rhyme in the middle of each stanza

These components are arranged into the following:

A1BA2 / ABA1 / ABA2 / ABA1 / ABA2 / ABA1A2

To make it easier, see this rhyme scheme in action with Dylan Thomas’ “Do not go gentle into that good night.”

Contemporary villanelles remain just as tricky. Some contemporary poets have tried to make it even trickier, adding additional refrains or changing the rhyme scheme. For more inspiration, these contemporary villanelles offer great rhyme and insight.

Mad Girl’s Love Song by Sylvia Plath

Villainhelle by David Mills (an experimental form with 3 refrains, written by our wonderful instructor)

Learn more about the villanelle here:

Types of Poetry: The American Cinquain

Length: 5 lines of varying length

Stanzas: One cinquain

Metrical requirements: None

Rhyme scheme: None

While a cinquain is a five-lined stanza, it is also in itself a poem structure.

The American Cinquain was developed by Adelaide Crapsey, a 20th century poet who wrote hundreds of poems in this form. It goes as follows:

Line 1: 2 syllables

Line 2: 4 syllables

Line 3: 6 syllables

Line 4: 8 syllables

Line 5: 2 syllables.

Here’s an example from Adelaide Crapsey herself, retrieved here:

Triad

These be

three silent things:

The falling snow . . . the hour

Before the dawn . . . the mouth of one

Just dead.

This short poetry form forces the poet to write with concision. Images and their juxtapositions matter far more than metaphor. Notice how surprising that last line is, how it comes so unexpectedly, how much we can learn in its ironic similarities with snow and the dawn. Crapsey’s poetics have often been compared to that of the tanka or haiku.

Here are some other examples of the American Cinquain:

Cinquains written during a tropical storm by Urayoán Noel

November Night by Adelaide Crapsey

Amaze by Adelaide Crapsey

There are plenty of innovations on the American Cinquain form, including the double cinquain, butterfly cinquain, lanterne, and others. You can learn more about these types of poetry here:

https://writers.com/cinquain-poetry

Types of Poetry: The Pantoum

Length: Any length, though often these are 4 stanzas long.

Stanzas: Quatrains.

Metrical requirements: None.

Rhyme scheme: None, but two lines of one stanza are repeated in the next.

The pantoum poetry form hails from Malaysia. In fact, its Malaysian form likely predates the written word, and it is much more complicated than the form that contemporary English-language poets write.

To write a pantoum in English, the poet must repeat the second and fourth lines of one stanza as the first and third lines, respectively, in the next.

Some poets repeat lines from the first stanza in the last stanza, too. If you were writing a 4 quatrain pantoum, here’s what it might be structured as:

Stanza 1

Line A

Line B

Line C

Line D

Stanza 2

Line B

Line E

Line D

Line F

Stanza 3

Line E

Line G

Line F

Line H

Stanza 4

Line G

Line I (or A)

Line H

Line J (or A, or C)

Here’s an example of this type of poetry, retrieved here.

“Descent of the Composer” by Airea D. Matthews

When I mention the ravages of now, I mean to say, then.

I mean to say the rough-hewn edges of time and space,

a continuum that folds back on itself in furtive attempts

to witness what was, what is, and what will be. But what

I actually mean is that time and space have rough-hewn edges.

Do I know this for sure? No, I’m no astrophysicist. I have yet

to witness what was, what is, and what will be. But what

I do know, I know well: bodies defying spatial constraint.

Do I know this for sure? No, I’m no scientist. I have yet

to prove that defiant bodies even exist as a theory; I offer

what I know. I know damn well my body craves the past tense,

a planet in chronic retrograde, searching for sun’s shadow.

As proof that defiant bodies exist in theory, I even offer

what key evidence I have: my life and Mercury’s swift orbits, or

two planets in chronic retrograde, searching for sun’s shadow.

Which is to say, two objects willfully disappearing from present view.

Perhaps life is nothing more than swift solar orbits, or dual

folds along a continuum that collapse the end and the beginning,

which implies people can move in reverse, will their own vanishing;

or at least relive the ravages of then—right here, right now.

This slow, melodic poem circumnavigates the pain of addiction recovery. By lamenting both the desire to return to the past and the uncertainty of the future, Matthews uses the pantoum to show how the certain past is constantly echoed in the uncertain present. These types of poetry forms, in which repetition links each stanza together, are often useful for ruminating on the past’s continuation in the present.

Here are some more examples of the pantoum poem structure:

“Eclipse Season” by Tracy Fuad

“Pantoum for Love and Fire” by Anointing Obuh

“Pantoum from the Window of the Room Where I Write” by Alison Townsend

Learn more about the pantoum poetry form here:

https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-pantoum-poem

Types of Poetry: The Free Verse Poem

Length: Variable

Stanzas: Variable

Metrical requirements: Variable

Rhyme scheme: Variable

Ah, free verse. That open space of nonconforming anythingness. That great beacon of poetic possibility. Nothing and everything can fit into the space of free verse, the poet’s version of a blank page. No rhymes to jail us. No meters to constrict us. That perilous python of poetry will not wrap its scaled and coiled tail around contemporary poets any longer, or my name isn’t T. S. Eliot!

And it isn’t. Free verse poetry doesn’t have metrical requirements, but that doesn’t mean it’s a free-for-all. Rather than relying on meter or rhyme to achieve the poem’s euphony, free verse poetry uses images, internal rhymes, and other poetic devices to search for deeper meaning.

That doesn’t mean free verse poems are constructed willy-nilly (though they can be!). Just like Terrance Hayes’ American Sonnets, form follows language. You might write a sequence of non-rhyming couplets, like instructor Jonathan McClure does in “A Prayer”; or, you might explore the staccato of 1s and 0s like Franny Choi does in “Turing Test”.

Some forms of poetry tend to be free verse. This isn’t to say they are free verse forms, but they are forms of poetry typically written in free verse. These include:

- Ode poetry

- Ekphrastic poetry

- Dirges

- Elegies

- Aubades

To learn more about writing free verse poems, check out our article on the topic.

https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-free-verse-poem

If you don’t see a rhyme scheme or meter, it’s probably free verse. So, rather than recommend great free verse poems, I’ll recommend some websites with great poetry archives. Modern poets certainly use poetry forms and structure, but they just as frequently invent their own forms, so try exploring the relationship between form and language in everything you read and write.

Poetry Foundation

Poets.org

Lit Hub

Types of Poetry: The Narrative Poem

Length: It varies greatly, but it’s longer than just a page.

Stanzas: It varies greatly. Many examples are isometric.

Metrical requirements: Older poetry, yes; contemporary, not so much.

Rhyme scheme: Older poetry, yes; contemporary, not so much.

The narrative poem is likely the oldest form of literature. Before the written word, people told stories in verse. In fact, many of the sonic devices in poetry, such as rhyme, meter, and alliteration, were mnemonic devices for storytellers to remember their verses.

Ancient narrative poetry certainly required rhyme and meter. Any student of works like The Aeneid, The Iliad and the Odyssey, or Beowulf will be acquainted with iambic pentameter or dactylic hexameter. However, contemporary examples of narrative poetry don’t rely on meter or rhyme; they are more interested in using poetic form as a vehicle for storytelling.

The narrative poem is distinct from the lyric poem, in that a narrative poem tells a story, with plot and characters and settings. Lyric poetry can best be described as a moment of emotion crystalized in language: what happens in the poem happens in merely an instant of thought or feeling.

“Trevor” by Ocean Vuong is a good example of a (relatively) short narrative poem. Longer examples includes novels-in-verse, such as Omeros by Derek Walcott or Autobiography of Red by Anne Carson.

For reference, all the other types of poetry in this article are lyric poetry forms. You can better understand the dichotomy between lyric and narrative poetry here:

https://writers.com/narrative-poem-definition

Types of Poetry: The Prose Poem

Length: It varies, but typically no longer than 3 pages.

Stanzas: None—it’s written in paragraphs.

Metrical requirements: None.

Rhyme scheme: None.

Prose poetry refers to a poem written in prose, rather than in verse. By that, we mean the poem is constructed in sentences and paragraphs, as opposed to lines and stanzas.

There’s no clear definition of what makes a prose poem. However, a few traits unite most prose poetry:

- Experimentations in syntax and sentence structure.

- A charting of the unconscious mind.

- The use of poetic and sonic devices, from metaphors and symbols to assonance and consonance.

Prose poems were written as early as Baudelaire in the mid-19th century, and then re-popularized in the 20th century. Several poetic movements, from the modernists to the objectivists, projectivists, and language poets, dabbled in the form to uncover new modes of language play.

You can see these elements of the prose poem at play in these three pieces by our phenomenal instructor Barbara Henning.

Learn more about the prose poem here:

https://writers.com/prose-poetry-definition

Types of Poetry: The Blackout Poem / Erasure Poem

Length: It varies.

Stanzas: None.

Metrical requirements: None.

Rhyme scheme: None.

Blackout poetry (and its cousin, found poetry) are distinct from other types of poetry in this article, because they rely on amending and stitching texts into poetry.

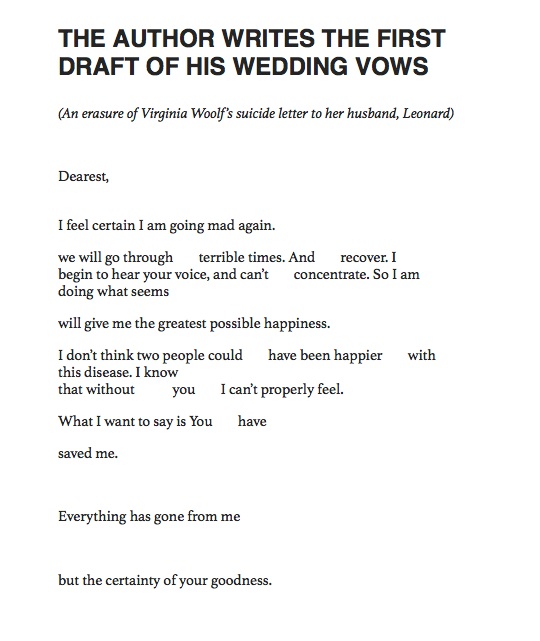

A blackout poem is a poem in which a piece of text has been blacked out, so that only the remaining words form a poem. If the text has been erased instead of blacked out, it’s typically called an erasure poem. See the below erasure poem, crafted by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib:

The source text is Virginia Woolf’s suicide letter to her husband, Leonard. Hanif’s erasures have created a new text, wherein the speaker is saved by the madness of love, yet the poem is still haunted by the heaviness of grief. It’s a beautiful, mesmerizing piece.

Great blackout poetry creates intertextuality, reacting to the source text while still crafting a wholly new poem.

Found poetry refers to poetry that’s either been discovered in real life, or poetry that’s been stitched and collaged from various media. If this interests you, check out the Frankenpo form invented by Kenji C. Liu.

Learn more about blackout poetry here:

https://writers.com/what-is-blackout-poetry-examples-and-inspiration

Explore More Forms of Poetry at Writers.com

Truthfully, there are hundreds of types of poetry forms that we haven’t included in this article. The history of poetry supersedes geography and language, so we have yet to touch on poetry from South Asia, East Asia, Latin America, Africa, as well as the many forms that emerged from just the 20th and 21st centuries.

Here’s the good news: your exploration of form has only just begun! A poetry course at Writers.com will help you further explore poetry forms and poem structure. Take a look at our upcoming poetry classes, and in the meantime, try your hand at the sestina or the limerick. Better yet, invent your own poetry form!

Excellent information, simply expressed. Thanks very much.

We’re happy you learned something!

Your site has explained the features of poetry in such a simple, lucid and relatable manner!

Truly grateful to be able to refer this site for all poetry study related queries . Keep up the great work.

Excellent.

[…] a very simple definition (not mine, but one from writer’s.com) is that “Poetry forms are defined as poetic structures used across multiple poems, generally by […]

Astute,yet complete…..Food for thought.

This article was pretty crazy tbh. I’m definitely learning from this!

Thanks much. The content is very comprehensive and easy to understand. Kudos to the team!

This is so educative, informative and easy to understand. Thank you

Sean, this is a very helpful piece! Thank you for posting this. And on a personal note, now I see how to revise my pantoum. So thanks for that, too. 🙏🏻

You’re very welcome, Lynne!

Very details and informative article and very helpful English literature students

Brilliant! You are an excellent teacher, Sean. If only other teachers/authors got straight to the essence of things as you do, instead of losing us on the byways. What classes do you teach?

i got everything i needed, am giving me email address for more updates concerning poetry

Awesome its really very useful for English literature students

Wow… I’ve written my own poetry for 30 years as basically free verse with a rhyming scheme… anywhere from 4 stanzas to 18 with the last word of the second and fourth lines of each stanza rhyming and sometimes the first and third lines rhyming… But I never learned anything about poetry until now. I just loved finessing words to make my rhyming points… Thanks for the lessons…I learned quite a bit.

I’m glad this was helpful, Scottie!

Thank you for this! Gonna use this to my World Literature class with my college students. Big help!

Very helpful content. I appreciate the effort.

[…] narrative poem is a form of poetry that is used to tell a story. The poet combines elements of storytelling—like plot, setting, and […]