A villanelle poem is a 19-lined formal poem that, although developed in the 17th century, was particularly prominent in the 20th. In fact, you have probably read or studied some villanelle examples in high school or beyond, such as Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” or Dylan Thomas’ “Do not go gentle into that good night.”

The villanelle form often lets poets dwell on obsession, and you’ll find in some of the famous villanelle poems we share how the structure of a villanelle contributes to lyrical, obsessive writing. Poets tend to feel things deeply, and this form gives poets license to put those feelings on the page.

This article examines how to write a villanelle poem, with particular attention to both form and content. But first, we need to define this popular and intricate poetry form. What is a villanelle poem?

Villanelle Definition: What is a Villanelle Poem?

A villanelle poem is a 19-lined poem broken up into 5 tercets and 1 quatrain. The poem has two different end rhymes running through it, and two different “refrains”—lines that are repeated throughout the poem.

Villanelle Definition: A 19-lined poem composed of 5 tercets and 1 quatrain, with two repeating end rhymes and two refrains.

Villanelle poetry has historically focused on topics of obsession for the poet, though more contemporary examples use the form to put unalike ideas in conversation with one another.

The most evocative part of a villanelle poem is, typically, the repeating refrains. As each refrain is re-employed in the poem, the lines adjacent to each refrain give the words new meaning, making the poem multifaceted and gleaming—a gemstone in the light.

You can see this for yourself in “One Art” by Elizabeth Bishop, one of the more well known villanelle examples in 20th century literature. Lines 1 and 3 are the refrains; take note of how each line is repeated in the poem.

One Art

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

Retrieved from Poetry Foundation.

Notice how each iteration of each refrain communicates something new to the poem, despite using the same or similar words. Notice, also, how you hardly notice the rhyme scheme while reading this poem. We’ll dissect how to do this in our section on how to write a villanelle poem!

The Structure of a Villanelle

Let’s dissect the structure of a villanelle. Once this structure is laid out visually, it isn’t too hard to understand it—though of course, writing it is still tricky.

If you aren’t familiar with rhyme schemes, meter, or the other elements of formal poetry, brush up on those topics in our article What is Form in Poetry?

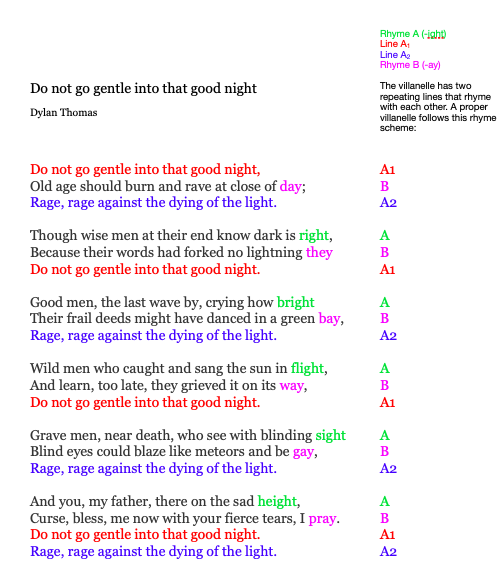

The villanelle rhyme scheme is mapped out in the above image—a copy of the poem “Do not go gentle into that good night” by Dylan Thomas. There is an A rhyme and a B rhyme. The two refrains, A1 and A2, always rhyme with the A rhyme; never the B rhyme. The B rhyme is always the second line of each stanza.

To reiterate, the villanelle rhyme scheme is as follows:

A1

B

A2

A

B

A1

A

B

A2

A

B

A1

A

B

A2

A

B

A1

A2

Typically, the structure of a villanelle does not have a particular meter. That is, you do not need to write your poem specifically in iambic pentameter. But, you will notice that a villanelle often is metrically uniform. Dylan Thomas does employ iambic pentameter. Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” has tercets of 11, 10, and 11 syllables, respectively.

Contemporary poets have tended to modify or break this structure if it better suits the language of their poem. We’ll point this out in the villanelle examples shared in this article.

Let’s see the structure of a villanelle in action now through some examples of the form.

Villanelle Poem Examples

The following villanelle poem examples come from living, contemporary poets. Pay attention to the musicality of each piece, and how the meaning of each refrain evolves throughout the poem. Read these poems like a poet!

“Instructions for the Hostage” by Erin Belieu

Originally published in The Kenyon Review, retrieved from Project Muse.

You must accept the door is never shut.

You’re always free to leave at any time,

though the hostage will remain, no matter what.

The damage could be managed, so you thought,

essential to the theory of your crime:

you must accept the door is never shut.

Soon, you’ll need to choose which parts to cut

for proof of life, then settle on your spine—

though the hostage will remain, no matter what.

Buried with a straw, it’s the weak that start

considering their price. You’re no great sum.

You must accept the door is never shut,

and make a half-life there, aware, apart,

afraid your captor has misplaced you, so far down,

though the hostage you’ll remain, no matter what.

Blink once for yes, and twice for yes—the heart

has a signal for the willing, its purity sublime.

You must accept the door was never shut,

though the hostage will remain, no matter what.

The language of this poem is simply haunting. Without any context for the hostage situation—is it real or a metaphor? How does it apply to our own lives?—the poem unsettles the reader, with paradoxical refrains weaving throughout the piece. How can you be a hostage, yet the door is always open? The poem doesn’t try to answer its own questions, but those questions lodge in the reader’s mind long after the poem ends.

You might notice that this poem breaks from the prescribed villanelle rhyme scheme. Stanzas 4 and 5 don’t have a B rhyme. Perhaps this break from form adds to the sense of “misplacement” in stanza 5, or suggests that a hostage situation is never as clean and formulaic as the captor wants it to be. There are many ways to interpret this, so read the poem several times, and try to engage with the language, its twists and turns, its oddities.

“Personal History” by Adrienne Su

Originally published in Poets.org’s “Poem-a-Day”

The world’s largest Confederate monument

was too big to perceive on my earliest trips to the park.

Unlike my parents, I was not an immigrant

but learned, in speech and writing, to represent.

Picnicking at the foot and sometimes peak

of the world’s largest Confederate monument,

we raised our Cokes to the first Georgian president.

His daughter was nine like me, but Jimmy Carter,

unlike my father, was not an immigrant.

Teachers and tour guides stressed the achievement

of turning three vertical granite acres into art.

Since no one called it a Confederate monument,

it remained invisible, like outdated wallpaper meant

long ago to be stripped. Nothing at Stone Mountain Park

echoed my ancestry, but it’s normal for immigrants

not to see themselves in landmarks. On summer nights,

fireworks and laser shows obscured, with sparks,

the world’s largest Confederate monument.

Our story began when my parents arrived as immigrants.

The two refrain lines cleverly juxtapose the speaker’s immigrant narrative against the dominating Confederate monument. More clever, still, is the fact that these two refrains don’t rhyme—it’s a slant rhyme, which conveys some level of discord between the two interweaving narratives.

Notice, also, how the poem elucidates on the immigrant narrative, but the wording of “the world’s largest Confederate monument” doesn’t vary much. This helps portray the monument as an immovable monolith, while the immigrant experience is varied, multifaceted, and often neglected. Such skillful employment of each refrain makes this a subtle and highly effective villanelle poem.

“Villanelle” by Campbell McGrath

Retrieved from Poetry Foundation’s July/August 2006 “Humor Issue.”

Bouncing along like a punch-drunk bell,

its Provençal shoes too tight for English feet,

the villanelle is a form from hell.

Balletic as a tapir, strong as a gazelle,

strict rhyme and formal meter keep a beat

as tiresome as a punch-drunk bell-

hop talking hip hop at the IHOP—no substitutions

on menu items, no fries with the chimichanga,

no extra syrup—what the hell

was that? Where did my rhyme go—uh, compel—

almost missed it again, damn, can you feel the heat

coming off this sucker? Red hot! Ding! (Sound of a bell.)

Hey, do I look like a bellhop to you, like an el-

evator operator, like a trained monkey or a parakeet

singing in my cage? Get the hell

out of the Poetry Hotel!

defeat mesquite tis mete repeat

Bouncing along like a punch-drunk bell,

the villanelle is a form from—Write it!—hell.

This ironic twist on an ars poetica might not be the best written. Arguably, some of the lines are lazy or sloppy (defeat mesquite tis mete repeat? Please!). But the poem is also trying to resist the strictness inherent to the structure of a villanelle, even as it acknowledges its own poetic history (such as the “Write it!” from “One Art” by Elizabeth Bishop).

If anything, this is actually a really fun challenge to do with formal poetry. How do you use the form of a poem against itself? How do you write a poem that’s both formal and funny? Take note of how McGrath both uses and refuses convention, playing with words mischievously while still conveying a clear argument.

“Villanelle with a Refrain from the Wall Street Journal” by Andrew Hudgins

Your twenties, thirties, forties, you’re a bull—

if you think of life as something like the Dow.

Though death of course is unavoidable,

you’re rising so fast rising’s almost dull,

your daily highs untested by a low.

Your twenties, thirties, forties, you’re a bull,

and life, for now, is fast and overfull—

for now, you might say, chuckling, for now—

though death, of course, is unavoidable.

You’re savvy enough, I’m sure, and fully able

to plan for when the market starts to slow.

Your twenties, thirties, forties, you’re a bull,

and all your hours, all, are billable,

as you tell others what, but mostly how,

though death, of course, is unavoidable.

Like contracts, life is fully voidable,

allow deferring soon to disallow.

Your twenties, thirties, forties, you’re a bull,

though death, of course, is unavoidable.

This villanelle poem doesn’t resist satire, or the urge to point out the folly of the rich. The refrain lines stand in stark contrast against each other, reminding the reader that money has no value after death, and also reminding the reader that the perils of the stock market, like death, prove unavoidable.

Hudgins’ poem was written and published shortly after the ‘08 market crash, and this poem captures the anger, resentment, and fear coursing through the zeitgeist of the aughts. Is life really worth living when it’s at the whims of money and the stock market? How can we live better lives outside of this financial paradigm?

More Villanelle Poem Examples

For more poems to inspire, provoke, and challenge your reading and writing, read the following villanelle examples.

- “Mad Girl’s Love Song” by Sylvia Plath

- “The Waking” by Theodore Roethke

- “Missing Dates” by William Empson

- “I am Not a Myth” by Matthew Hittinger

- “Miranda” by W. H. Auden

- “The House on the Hill” by Edwin Arlington Robinson

- “Improvisation on Lines by Isaac the Blind” by Peter Cole

- “The World and the Child” by James Merrill

- “Broad Arrow Cafe” by Joe Dolce

- “My Darling Turns to Poetry at Night” by Anthony Lawrence

- “Poem” by James Schuyler

Experimental Villanelle Poem Examples

Poets can’t leave form alone. While the classic structure of a villanelle continues to serve poets well, contemporary poets have also tinkered quite liberally with the length, form, and requirements of the poem. What happens when you add extra stanzas? A third refrain? Why not play around with every word in the second refrain, and see what happens?

Experimentations in form should be done with intent. They should draw your eye towards something unique in the language, or else work within the context of the poem as a whole to deepen the poem’s meaning. Read and enjoy the following villanelle poems closely, with attention to how the form has been broken or expanded.

- “Are you not weary of ardent ways” by James Joyce

- “Villainhelle” by David Mills (our talented instructor!)

- “Twerk” by Porsha Olayiwola

- “Testimony: 1968” by Rita Dove

See also the terzanelle, a form that combines the villanelle and the terza rima.

How to Write a Villanelle Poem

For poets seeking to conquer the form, here’s some advice on how to write a villanelle poem.

1. Sharpen Your Refrains

The refrains of a villanelle are usually the most memorable lines of the poem. They are also the lines that form the poem’s backbone. 8 of the poem’s 19 lines are refrain lines, so when you hone these, you’ve already written about 40% of the poem!

Here are some considerations for crafting strong villanelle refrains:

- How do the two lines interact with each other? Do they complement each other, or do they clash? Side by side, each refrain should deepen and/or complicate the other one’s meaning.

- Do the lines rhyme? Do they slant rhyme? Does one line remain stable, while the other one is modified throughout the poem? (Some modification is acceptable within the standard structure of a villanelle.)

- Does each refrain have the same number of syllables? The same meter? If not, do they still have a certain rhythm with each other?

2. Be Intentional With Form

The villanelle is a highly formal poem. As such, the poet should be highly intentional with form.

Pay attention to how poets play with the form in any of the villanelle poem examples we’ve shared. Get granular: count the number of syllables in each line, pay attention to how refrains are preserved or modified in each stanza, listen to how the rhyme scheme adds to or inhibits this flow, etc.

Then, make decisions within the context of your own poem. Do you want your refrain lines to get along, or to clash with each other? Do you want the rhyme scheme to flow from one line to the next, or do you want to play with poetic devices like cacophony?

3. Write Patiently and Slowly

Reading some of the villanelles we’ve shared in this article, poets make the form look easy. In reality, the villanelle form requires slow, patient work.

Don’t expect the poem to be perfect in a first draft, and don’t expect the words to come quickly. When you’re working within the confines of rhyming words and syllable constraints, finding the right words requires a lot of close, careful attention to language.

Rather, let yourself be challenged by the form. Expect difficulty, rather than immediate reward. You will find that the villanelle produces some incredibly powerful lines, but only if you lean into the work. It may take weeks, even months of tinkering with words, but the poetic payout can prove immense.

4. Read Out Loud, and Count Your Syllables

When you have a first draft, read it out loud. How does each line sound? Does it flow the way you want it to? Does the rhythm help spotlight the language? Do you find each stanza complicating the meaning of the refrains?

Count your syllables, too. Even if you aren’t trying to be metrically uniform, you might notice that certain lines read awkwardly, and that they have one syllable too many or too few.

Lastly, take note of the villanelle rhyme scheme. Do you notice the rhymes as you read the poem? If they stand out or feel awkward in the poem, it’s probably because some of the rhyming words aren’t essential; rather, they were shoehorned in to meet the structural requirements. This is the most dangerous part of rhymes—that they can support form without supporting the poem as a whole. Take note when this happens, and plan to revise.

Read your poem out loud a couple of times, and perhaps circle the words that are doing the least work or are inhibiting the flow of the poem.

5. Revise Ruthlessly, Relentlessly

You might need to break down entire stanzas to get the language right. You might even realize your refrains aren’t working the way you want them too. Again, the villanelle is a challenging form. It demands a lot from the poet, it’s slippery as an eel, and there aren’t any cheap tricks or easy craft fixes to produce a powerful poem.

Be open to experimentation and change in the revision process. Save every draft you write, and be willing to tear everything apart, to move stanzas around, to spend hours tinkering on a single word.

You might also find opportunities to break with the standard villanelle form. If you do this, do it with intention. Breaks in form shouldn’t be incidental or convenient, but they should be put in conversation with the content of the poem itself.

Put Form to Poetry at Writers.com

Want to try your hand at formal poetry in a writing class? Take a look at the upcoming poetry courses at Writers.com, where you’ll receive expert feedback on every poem you write, whether it’s free verse, prosaic, or formal like a villanelle.

very helpful thanks

Sean, this is the most informed, considered and creative article on writing the villanelle I’ve come across. I referred to it as I composed a villanelle for a submission call a few months ago, and it was accepted. I was patient, ruthless and It went through several iterations before I felt it had “arrived”, Thank you so much for all your process tips & the stunning array of example villanelles. It makes an indispensable resource.

Hi Melissa,

Congratulations on your poetry acceptance! I would love to read your poem, if you’re comfortable sharing it with me? I’d even like to share it in our newsletter if you’re comfortable with that. I’m so glad this resource could help you write your villanelle. Happy writing!

Hi Sean,

I’m sorry about the delay in reply. This website doesn’t appear to notify one of new comments, so luckily I came back to peruse the list of villanelles and saw your reply today! Yes, I’m happy to share the link for you to read. It isn’t directly on Quill & Crow’s website, but the issue is available via a free downloadable PDF (also hard copy mag available to purchase) at the link below. Happy for you to also share the link in your newsletter, but just a note that my contract stipulates I can’t republish the poem in full anywhere for 5 more months.

https://www.quillandcrowpublishinghouse.com/cqmagazine2023

I’d be comfortable with you sharing the first verse in the newsletter and then the link. I just used that approach myself in a how-to piece on writing the vilanelle that was published on Medium.com.

If you’d like a more direct way to contact me, my email address is: ask.the.seeds [at] gmail.com

Thanks again for your interest!

Thank you, Melissa! We will include a link to your poem in our newsletter on Tuesday. Congratulations again!

Wonderful, Sean. Thank you. I don’t think I’ve signed up to Writers.com newsletter. How do I get myself on the list? 🙂

I’ve just added you! You’ll receive our newsletter every Tuesday 🙂