What do the words “anaphora,” “enjambment,” “consonance,” and “euphony” have in common? They are all literary devices in poetry—and important poetic devices, at that. Your poetry will be greatly enriched by mastery over the items in this poetic devices list, including mastery over the sound devices in poetry.

This article is specific to the literary devices in poetry. Before you read this article, make sure you also read our list of common literary devices across both poetry and prose, which discusses metaphor, juxtaposition, and other essential figures of speech.

We will be analyzing and identifying poetic devices in this article, using the poetry of Margaret Atwood, Louise Glück, Shakespeare, and others. We also examine sound devices in poetry as distinct yet essential components of the craft.

Poetic Devices: Contents

Literary Devices in Poetry: Poetic Devices List

Let’s examine the essential literary devices in poetry, with examples. Try to include these poetic devices in your next finished poems!

1. Anaphora

Anaphora describes a poem that repeats the same phrase at the beginning of each line. Sometimes the anaphora is a central element of the poem’s construction; other times, poets only use anaphora in one or two stanzas, not the whole piece.

Consider “The Delight Song of Tsoai-talee” by N. Scott Momaday.

I am a feather on the bright sky

I am the blue horse that runs in the plain

I am the fish that rolls, shining, in the water

I am the shadow that follows a child

I am the evening light, the lustre of meadows

I am an eagle playing with the wind

I am a cluster of bright beads

I am the farthest star

I am the cold of dawn

I am the roaring of the rain

I am the glitter on the crust of the snow

I am the long track of the moon in a lake

I am a flame of four colors

I am a deer standing away in the dusk

I am a field of sumac and the pomme blanche

I am an angle of geese in the winter sky

I am the hunger of a young wolf

I am the whole dream of these things

You see, I am alive, I am alive

I stand in good relation to the earth

I stand in good relation to the gods

I stand in good relation to all that is beautiful

I stand in good relation to the daughter of Tsen-tainte

You see, I am alive, I am alive

This poem is an experiment in metaphor: how many ways can the self be reproduced after “I am”? The simple “I am” anaphora draws attention towards the poet’s increasing need to define himself, while also setting the poet up for a series of well-crafted poetic devices.

Anaphora describes a poem that repeats the same phrase at the beginning of each line.

The self shapes the core of Momaday’s poem, as emphasized by the anaphora. Still, our eye isn’t drawn to the column of I am’s, but rather to Momaday’s stunning metaphors for selfhood.

Article continues below…

Poetry Writing Courses We Think You'll Love

We've hand-picked these courses to help you flourish as a writer.

Crafting Poems in Form: Rhyme, Meter, Fixed Forms, and More

Working within the guidelines of a fixed poetic structure can make your poetry more creative, not less. Find freedom in...

Find Out MoreOr click below to view all courses.

See CoursesArticle continues…

2. Conceit

A conceit is, essentially, an extended metaphor. Which, when you think about it, it’s kind of stuck-up to have a fancy word for an extended metaphor, so a conceit is pretty conceited, don’t you think?

In order for a metaphor to be a conceit, it must run through the entire poem and be the poem’s central device. Consider the poem “The Flea” by John Donne. The speaker uses the flea as a conceit for physical relations, arguing that two bodies have already intermingled if they’ve shared the odious bed bug. With the flea as a conceit for intimacy, Donne presents a poem both humorous and strangely erotic.

A conceit must run through the entire poem as the poem’s central device.

The conceit ranks among the most powerful literary devices in poetry. In your own poetry, you can employ a conceit by exploring one metaphor in depth. For example, if you were to use matchsticks as a metaphor for love, you could explore love in all its intensity: love as a stroke of luck against a matchbox strip, love as wildfire, love as different matchbox designs, love as phillumeny, etc.

3. Apostrophe

Don’t confuse this with the punctuation mark for possessive nouns—the literary device apostrophe is different. Apostrophe describes any instance when the speaker talks to a person or object that is absent from the poem. Poets employ apostrophe when they speak to the dead or to a long lost lover, but they also use apostrophe when writing an ode to something, such as Ode to a Grecian Urn or an Ode to the Women in Long Island.

Apostrophe is often employed in admiration or longing, as we often talk about things far away in wistfulness or praise. Still, try using apostrophe to express other emotions: express joy, grief, fear, anger, despair, jealousy, or ecstasy, as this poetic device can prove very powerful for poetry writers.

4. Metonymy & Synecdoche

Metonymy and synecdoche are very similar poetic devices, so we’ll include them as one item. A metonymy is when the writer replaces “a part for a part,” choosing one noun to describe a different noun. For example, in the phrase “the pen is mightier than the sword,” the pen is a metonymy for writing and the sword is a metonymy for fighting.

Metonymy: a part for a part.

In this sense, metonymy is very similar to symbolism, because the pen represents the idea of writing. The difference is, a pen is directly related to writing, whereas symbols are not always related to the concepts they represent. A dove might symbolize peace, but doves, in reality, have very little to do with peace.

Synecdoche is a form of metonymy, but instead of “a part for a part,” the writer substitutes “a part for a whole.” In other words, they represent an object with only a distinct part of the object. If I described your car as “a nice set of wheels,” then I’m using synecdoche to refer to your car. I’m also using synecdoche if I call your laptop an “overpriced sound system.”

Synecdoche: a part for a whole.

Since metonymy and synecdoche are forms of symbolism, they appear regularly in poetry both contemporary and classic. Take, for example, this passage from Shakespeare’s A Midsommar Night’s Dream:

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Shakespeare makes it seem like the poet’s pen gives shape to airy wonderings, when in fact it’s the poet’s imagination. Thus, the pen becomes metonymous for the magic of poetry—quite a lofty comparison, which only a bard like Shakespeare could say.

5. Enjambment & End-Stopped Lines

Poets have something at their disposal which prose writers don’t: the mighty line break. Line breaks and stanza breaks help guide the reader through the poem, and while these might not be hardline “literary devices in poetry,” they’re important to understanding the strategies of poetry writing.

Line breaks can be one of two things: enjambed or end-stopped. End-stopped lines are lines which end on a period or on a natural break in the sentence. Enjambment, by contrast, refers to a line break that interrupts the flow of a sentence: either the line usually doesn’t end with punctuation, and the thought continues on the next line.

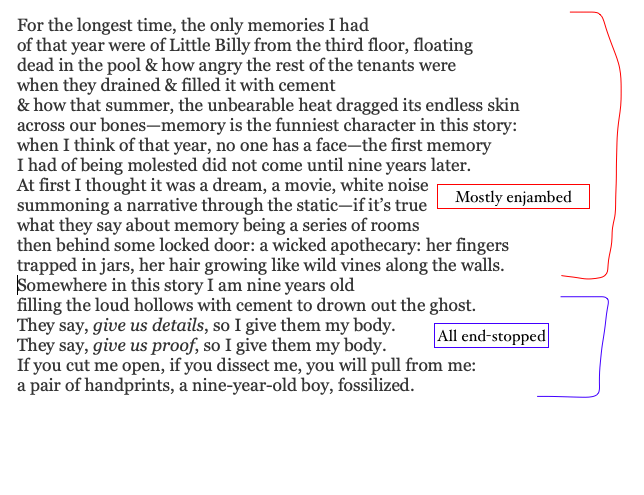

Let’s see enjambed and end-stopped lines in action, using “The Study” by Hieu Minh Nguyen.

Most of the poem’s lines are enjambed, using very few end-stops, perhaps to mirror the endless weight of midsummer. Suddenly, the poem shifts to end-stops at the end, and the mood of the poem transitions: suddenly the poem is final, concrete in its horror, horrifying perhaps for its sincerity and surprising shift in tone.

Line breaks and stanza breaks help guide the reader through the poem.

Enjambment and end-stopping are ways of reflecting and refracting the poem’s mood. Spend time in your own poetry determining how the mood of your poems shift and transform, and consider using this poetry writing strategy to reflect that.

6. Zeugma

Zeugma (pronounced: zoyg-muh) is a fun little device you don’t see often in contemporary poetry—it was much more common in ancient Greek and Latin poetry, such as the poetry of Ovid. This might not be an “essential” device, but if you use it on your own poetry, you’ll stand out for your mastery of language and unique stylistic choices.

A zeugma occurs when one verb is used to mean two different things for two different objects. For example, I might say “He ate some pasta, and my heart out.” To eat pasta and eat someone’s heart out are two very different definitions for ate: one consumption is physical, the other is conceptual. The key here is to only use “ate” once in the sentence, as a zeugma should surprise the reader.

Now, take this excerpt from Ovid’s Heroides 7:

the same winds will bear away your promises and sails.

You are resolved, Aeneas, to weigh your anchor and your vows,

and go in quest of Italy, a land to which you are wholly a stranger.

Can you identify the zeugmas? “Bear” and “weigh” are both used literally and figuratively, bearing weight to the speaker’s laments.

Zeugmas are a largely classical device, because the constraints of ancient poetic meter were quite strict, and the economic nature of Latin encouraged the use of zeugma. Nonetheless, try using it in your own poetry—you might surprise yourself!

7. Repetition

Strategic repetition of certain phrases can reinforce the core of your poem.

Last but not least among the top literary devices in poetry, repetition is key. We’ve already seen repetition in some of the aforementioned poetic devices, like anaphora and conceit. Still, repetition deserves its own special mention.

Strategic repetition of certain phrases can reinforce the core of your poem. In fact, some poetry forms require repetition, such as the villanelle. In a villanelle, the first line must be repeated in lines 6, 12, and 18; the third line must be repeated in lines 9, 15, and 19.

See this repetition in action in Sylvia Plath’s “Mad Girl’s Love Song.” Notice how the two repeated lines reinforce the subjects of both love and madness—perhaps finding them indistinguishable? Take note of this masterful repetition, and see where you can strategically repeat lines in your own poetry, too.

Learn more about this poetic device here:

Repetition Definition: Types of Repetition in Poetry and Prose

Sound Devices in Poetry

The other half of this article analyzes the different sound devices in poetry. These poetic sound devices are primarily concerned with the musicality of language, and they are powerful poetic devices for altering the poem’s mood and emotion—often in subtle, surprising ways.

What are sound devices in poetry, and how do you use them? Let’s explore these other literary devices in poetry, with examples.

8. Internal & End Rhyme

When you think about poetry, the first thing you probably think of is “rhyme.” Yes, many poems rhyme, especially poetry in antiquity. However, contemporary poetry largely looks down upon poetry with strict rhyme schemes, and you’re far more likely to see internal rhyming than end rhyming.

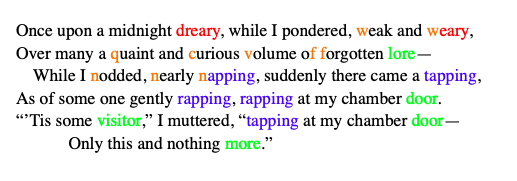

Internal rhyme is just what it sounds like: two rhyming words juxtaposed inside of the line, rather than at the end of the line. See internal rhyme in action Edgar Allan Poe’s famous “The Raven”:

Each of the rhymes have been assigned their own highlighted color. I’ve also highlighted examples of alliteration, which this article covers next.

Despite “The Raven’s” macabre, dreary undertones, the play with language in this poem is entertaining and, quite simply, fun. Not only does it draw readers into the poem, it makes the poem memorable—after all, poetry used to rhyme because rhyme schemes helped people remember the poetry, long before people had access to pen and paper.

Why does contemporary poetry frown at rhyme schemes? It’s not the rhyming itself that’s odious; rather, contemporary poetry is concerned with fresh, unique word choice, and rhyme schemes often limit the poet’s language, forcing them to use words which don’t quite fit.

contemporary poetry is concerned with fresh, unique word choice, and rhyme schemes often limit the poet’s language

If you can write a rhyming poem with precise, intelligent word choice, you’re an exception to the rule—and far more skilled at poetry than most. Perhaps you should have been born a bard in the 16th century, blessed with the king’s highest graces, splayed dramatically on a decadent chaise longue with maroon upholstery, dining on grapes and cheese.

9. Alliteration

Alliteration is a powerful, albeit subtle, means of controlling the poem’s mood.

One of the more defining sound devices in poetry, alliteration refers to the succession of words with similar sounds. For example: this sentence, so assiduously steeped in “s” sounds, was sculpted alliteratively. (This s-based alliteration is called sibilance!)

Alliteration is a powerful, albeit subtle, means of controlling the poem’s mood. A series of s’es might make the poem sound sinister, sneaky, or sharp; by contrast, a series of b’s, d’s, and p’s will give the poem a heavy, percussive sound, like sticks against a drum.

Emily Dickenson puts alliteration to play in her brief poem “Much Madness.” The poem is a cacophonous mix of s, m, and a sounds, and in this cacophony, the reader gets a glimpse into the mad array of the poet’s brain.

Alliteration can be further dissected; in fact, we could spend this entire article talking about alliteration if we wanted to. What’s most important is this: playing with alliterative sounds is a crucial aspect of poetry writing, helping readers experience the mood of your poetry.

10. Consonance & Assonance

Along with alliteration, consonance and assonance share the title for most important sound devices in poetry. Alliteration refers specifically to the sounds at the beginning: consonance and assonance refer to the sounds within words. Technically, alliteration is a form of consonance or assonance, and both can coexist powerfully on the same line.

Consonance refers to consonant sounds, whereas assonance refers to vowel sounds. You are much more likely to read examples of consonance, as there are many more consonants in the English alphabet, and these consonants are more highly defined than vowel sounds. Though assonance is a tougher poetic sound device, it still shows up routinely in contemporary poetry.

In fact, we’ve already seen examples of assonance in our section on internal rhyme! Internal rhymes often require assonance for the words to sound similar. To refer back to “The Raven,” the first line has assonance with the words “dreary,” “weak,” and “weary.” Additionally, the third line has consonance with “nodded, nearly napping.”

These poetic sound devices point towards one of two sounds: euphony or cacophony.

11. Euphony & Cacophony

Poems that master musicality will sound either euphonious or cacophonous. Euphony, from the Greek for “pleasant sounding,” refers to words or sentences which flow pleasantly and sound sweetly. Look towards any of the poems we’ve mentioned or the examples we’ve given, and euphony sings to you like the muses.

Cacophony is a bit harder to find in literature, though certainly not impossible. Cacophony is euphony’s antonym, “unpleasant sounding,” though the effect doesn’t have to be unpleasant to the reader. Usually, cacophony occurs when the poet uses harsh, staccato sounds repeatedly. Ks, Qus, Ls, and hard Gs can all generate cacophony, like they do in this line from “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” from Samuel Taylor Coleridge:

agape they heard me call.

Reading this line might not be “pleasant” in the conventional sense, but it does prime the reader to hear the speaker’s cacophonous call. Who else might sing in cacophony than the emotive, sea-worn sailor?

12. Meter

What’s something you still remember from high school English? Personally, I’ll always remember that Shakespeare wrote in iambic pentameter. I’ll also remember that iambic pentameter resembles a heartbeat: “love is a smoke made with the fumes of sighs.” ba-dum, ba-dum, ba-dum.

Metrical considerations are often reserved for classic poetry. When you hear someone talking about a poem using anapestic hexameter or trochaic tetrameter, they’re probably talking about Ovid and Petrarch, not Atwood and Glück.

Still, meter can affect how the reader moves and feels your poem, and some contemporary poets write in meter.

Before I offer any examples, let’s define meter. All syllables in the English language are either stressed or unstressed. We naturally emphasize certain syllables in English based on standards of pronunciation, so while we let words like “love,” “made,” and “the” dangle, we emphasize “smoke,” “fumes,” and “sighs.”

Depending on the context, some words can be stressed or unstressed, like “is.” Assembling words into metrical order can be tricky, but if the words flow without hesitation, you’ve conquered one of the trickiest sound devices in poetry.

Common metrical types include:

- Iamb: repetitions of unstressed-stressed syllables

- Anapest: repetitions of unstressed-unstressed-stressed syllables

- Trochee: repetitions of stressed-unstressed syllables

- Dactyl: repetitions of stressed-unstressed-unstressed syllables

Finding these prosodic considerations in contemporary poetry is challenging, but not impossible. Many poets in the earliest 20th century used meter, such as Edna St. Vincent Millay. Her poem, “Renascence,” built upon iambic tetrameter. Still, the contemporary landscape of poetry doesn’t have many poets using meter. Perhaps the next important metrical poet is you?

Learn more about meter here:

More Sound Devices

We cover other sound devices, including elision, homophony, and sibilance here:

Mastering the Literary Devices in Poetry

Every element of this poetic devices list could take months to master, and each of the sound devices in poetry requires its own special class. Luckily, the instructors at Writers.com know just how to sculpt poetry from language, and they’re ready to teach you, too. Take a look at our upcoming poetry courses, and take the next step in mastering the literary devices in poetry.

Very interesting stuff! I’m looking forward to incorporating some of these devices in my future poetry.

Incredible. Somes are new btw.

Wow … learned alot with this…. thanks

Well illustrated, simple language and easily understood.

Thank you.

While thinking of an appropriate inscription for my dad’s headstone, the following two thoughts came to mind:

“He served his country with honor and he honored his wife with love.”

Can the above be described as being an example of any particular kind of literary or poetic device?

Hi Louis, good question! This is an example of polyptoton, a repetition device in which words from the same root are employed simultaneously. You can learn more about it at this article: writers.com/repetition-definition

You’re also close to using what’s called a syllepsis or zeugma. From the Greek for “a yoking,” a zeugma is when you use the same verb to mean two different things. An example: “He ate his feelings–and the cheesecake.” “Ate” is being used both figuratively and literally, “yoking” the two meanings together.

Your sentence uses honor as both a noun and a verb, which makes it a bit distinct from other zeugmas. Regardless, it’s a thoughtful sentiment and a lovely sentence. I hope this helps!

It’s called a polyptoton.

Repetition, in close proximity, of different grammatical forms of the same root word. Honor/noun

Honored/ verb

It’s not zeugma when the word which would be yoked, is instead repeated.

I discovered this literary device one day, some years into my teaching career, by reading the literary dictionary with my students. We were very happy to find the term, after several students had inquired about a passage we were analyzing, and I had no answer (except a form of repetition).

The class cheered when I read it out. I can’t imagine that happening today…

Isn’t it alliteration… ‘h’ sound is repeated 🤔

It is an alliteration, zeugma, assonance, consonance

It is called a polyptoton — a literary device of repetition involving the use, in close proximity, of more than one grammatical form of the same word. In this case honor (noun) and honored (verb).

Famous example:

“The Greeks are strong and skilful in their strength,

Fierce to their skill, and to their fierceness valiant.”

Strong/strength & skilful/skill & fierce/fierceness = adjective/noun forms — in very close proximity (within a single sentence).

It’s a powerful dream of mine you just inspired me

These are very helpful! I am a poet, and I did not know about half of these! Thank you.

Hi Lily,

We’re so glad this article was helpful! Happy writing 🙂

I am definitely loving this article. I have learnt a lot.

Thank you so much for this article. it is quite refreshing and enlightening.

the article was helpful during my revisions

As apostrophe is used to make a noun possessive case, not plural. (#3)

Hi Penny,

You’re correct when it comes to the grammatical apostrophe, but as a literary device, apostrophe is specifically an address to someone or something that isn’t present in the work itself. For some odd reason, they share the same name. 🙂

You can learn more about the apostrophe literary device here. I hope this makes sense!

@Sean Glatch

I believe this comment was intended as a correction to the phrase ‘the punctuation mark for plural nouns’ used in the article. Plural nouns aren’t apostrophised, which makes that an error.

Very knowledgeable to learn, I want to learn more……

Thx

This is very helpful to me.

Very knowledgeable and detailed.

I think that a cool literary device to add would be irony. Its my favorite 🙂

Thanks, Patricia! We have an article on irony at this link.

Happy writing!

I am a student currently studying English Literature.

Really appreciate the article and the effort put into it because its made some topics more clear to me.

However, is there any place where I can find more examples of the devices Enjambement, metonymy, iambic pentameter, consonance & cacophony?

Would appreciate it a bunch❤

Thank you again for the article

I’m so glad this article was helpful! We cover a few more topics in poetry writing at this article: https://writers.com/what-is-form-in-poetry

in my high school in uganda, we study about these devices that’s if you offer literature as a subject

Very helpful and relevant…

I just came here to check out some poetic devices so that I can pass through my exam…but looking at these comments made me feel like…where am I? Is this the land of the angels? Thanks for the motivation, probably not a poet but I am writing stories now, made a good one already.

Very precious knowledge . Thanks alot.

Thank you, You have taught me a lot .

Really needed this for my AP Lit class, thanks for making it so understandable!

This article was extremely informative. I love the platform. Wonderful to find other individuals passionate about language. I absolutely enjoyed the discourse.

I have learnt a lot, may God bless you forever. Thank you so much.

This was very informative to read, thank you.

i do have one question. I have searched over the internet and I’m struggling to find my answer.

Do you know if there’s a name for when a poem starts with a rhetorical question in the beginning line, and then answers it in the very last line. Take ‘Who’s For the Game?’ by Jessie Pope as an example.

Thx

Fantastic thank you very helpful

ELA educator here; glad to have this well-written and concise information for my classroom! Thank you!

Instagram @jenlee_123

Thank you very much, I have learned a lot. Hopefully I’ll do the best in my assignments.

Thank you.

I polished my dusty knowledge of literature.

Thank you so much.

I needed this for my AP LIT exam.

Now I can write my essay

– Ish Da Fish

I needed a quick review and this is perfect.

Thank you.

Thank you

I have learned so much

I really gained a lot here

Learned new terminologies. It’s wonderful.

Thanks this is very helpful

Very helpful and informative