Poetry is the densest and richest use of language there is, and learning how to read poetry is an art in itself. Learning how to read poetry like a poet—to not only feel the impact of poetry but to have a sense of the craft elements that make that impact possible—even more so.

Reading poetry like a poet means both feeling the impact of poetry, and investigating the craft elements that enable that impact.

In this article, we’ll cover the basics of how to read poetry in such a way as to strengthen your own poetic sensibility.

Reading Poetry Like a Poet: Hearts Welcome!

We’re not suggesting that you learn how to read poetry like a professor or academic—which can potentially be dry, detached, and intellectual. Please bring your feelings with you; you’ll need them.

Rather, we’re exploring how, in the context of poetry, to read like a writer: how to identify what makes a poem effective (or not effective!) and using that as inspiration for your own work. A writer’s work must include lots of reading, and lots of reading effectively, and that’s what we’re here to cover.

How to Read Poetry: A Step-By-Step Poem Analysis

Any good teacher of poetry will tell you that a poem must be read multiple times to fully understand it. Well, that’s exactly what I’m going to walk you through. I’ll be doing a close reading of Ocean Vuong’s poem “Tell Me Something Good.” In this close reading, I’ll focus on four separate components:

- Identifying literary devices at use in the poem.

- Deconstructing the poet’s word choice: the meanings, rhythms, and musicality of the words in the poem;

- Analyzing the poem’s lineation (choice of line breaks, a key difference between poetry and prose) and stanza breaks;

- Seeking inspiration by combining these three interpretations.

Before you read my interpretation, read the poem for yourself at poets.org and draw your own conclusions. There are many possible understandings of this poem, so don’t accept my interpretation at face value!

1. How to Read Poetry: Examining Literary Devices

After reading the poem, one possible first step is to identify prominent literary devices. The devices you notice will likely be used multiple times in the poem, or they may only be used once but strike you in a meaningful way. For my analysis, I found the following six devices significant:

- Metaphor

- Simile

- Imagery

- Juxtaposition

- Diction (specifically, verb choice)

- Paradox

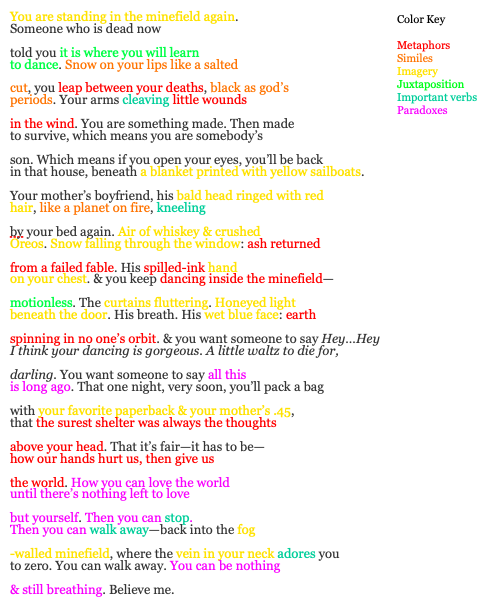

Below is the poem “Tell Me Something Good,” with figurative language and interesting word choice highlighted. Take a look for yourself, and then draw some conclusions. We want to investigate how the word choice reflects the author’s meaning, either through the use of figurative language or other forms of suggestion.

At first glance, this is clearly a poem packed with meaning. The poem alternates between strong imagery and strong metaphors and similes. There are also several statements that are self-contradictory, creating some powerful paradoxes and also a sense of wryness throughout the poem. If you haven’t heard of Ocean Vuong before, you can tell he’s an extremely strong poet.

Let’s start from the beginning. We begin with a minefield, and the odd juxtaposition of this minefield and a dance. What could that possibly mean? With little context, it’s hard to know what the poem refers to. At this point, however, it’s important to note this juxtaposition of life and death.

Building upon this juxtaposition, the poem moves towards metaphor. The line “snow on your lips like a salted / cut” continues the series of contrasting juxtapositions, since snow tastes pleasant on lips and salt on a cut burns like a fever.

As we move through the poem, it seems like Vuong’s language is constantly contradicting itself, folding into itself, questioning its own meaning. The speaker goes from dancing in a minefield to jumping between deaths “black as god’s periods”―a line that is intentionally subversive, coercing the reader to stop and consider.

Then, the speaker moves from the metaphoric to the real, telling a story of boyhood through strong, precise imagery. We can see the boy’s bedroom, his blanket with yellow sailboats a symbol of childhood, cowering next to a juxtaposition of whiskey and crushed Oreos.

Finally, these contradictions intensify into paradoxes. A paradox, briefly, is a self-negating statement―it contradicts itself yet still seems true. We often say “less is more” in daily speech, and though less and more are antonyms, the statement itself rings true.

For example, how can “all this”―the present―be “long ago”? How can you love the world into nothingness? How can you both stop and walk away? How can you be nothing and still breathing?

The poem’s final plea, “believe me,” tells us that the speaker knows how self-contradictory the poem seems. Yet, each of these paradoxes seem to be lived experiences. It’s up to us, as readers, to interpret these paradoxes for our own lives, even if they seem impossible. After all, aren’t our own lives filled with paradoxes? Isn’t life itself paradoxical?

2. How to Read Poetry: Deconstructing Word Choice

As a writer, there’s a lot to pull from the above analysis on figures of speech. It’s interesting to see a poem built entirely on contradiction, especially since the contradictions are so subtle and elusive.

Still, this analysis is lacking something, because individual words themselves carry great weight, and we need to think about those words as well.

We’ll start with verbs because they’re the most important part of speech―they give the sentence action, and they offer visual clues to help guide us through the poem. Take a look at the important verbs I highlighted:

- Cleaving

- Kneeling

- Stop

- Walk (away)

- Adore

Those five verbs, in order of appearance, set the poem’s foundation. They also re-tell the basic story: we begin with cleaving, a violent verb, then end on adoration, something positive. I’ve been waiting for this poem to “Tell Me Something Good,” and the “good” verb of the poem is “adore.”

Of course, context tells us something different. Cleaving is actually an innocent verb here―it’s just a boy cutting the air with his arms. “Adore,” by contrast, presents something ironic: a vein loving its body to death.

The man kneels next to the boy’s bed, which should be innocent because he’s bringing himself to the boy’s level; however, there’s something to fear here, reinforced by the boy running from home with his mother’s .45. Yet, don’t worry―if you simply stop, which means walking away, your hands can still give you the world.

These aren’t the only verbs of the poem, but they are verbs that offer contradictions, upholding the poem’s central vehicle (paradox). Since verbs provide the motion of a sentence, this poem’s movements are inherently paradoxical.

3. How to Read Poetry: Line Breaks & Stanzas

Before moving towards possibilities as a writer, we need to look at the poem’s form. Now, just because this is the last focus doesn’t mean it’s less important. Form influences how we read the poem, and as we consider this poem’s lineation, we are also considering how to use form in our own poetry.

Some observations:

- The poem is written in sets of couplets.

- Most of the lines in this poem don’t end with punctuation, making them enjambed―a fancy term for a sentence that continues into the following line of poetry.

- Most of the lines end on strong words (nouns and verbs).

- The ending line ends on a pronoun, “me.”

- The final stanza is a single line, thus breaking the procession of couplets.

What do these observations tell us about the poem? First, let’s ask ourselves why the poet used couplets to tell this story. It’s likely that these couplets build upon the tension from the poem’s incongruous juxtapositions.

Let’s treat each couplet as a “unit” in the poem. Once we do this, we notice further juxtapositions. For example, the second couplet uses soft, innocuous images: learning to dance, snow on lips. However, it’s sandwiched between two morbid couplets―the first about dying in a mine, the third about death, blood, wounds, and salted cuts. Yow!

The enjambed lines also affect the way we read this poem. Because one couplet usually flows into the next, we are sped through the poem and actually have to slow down to notice all of these images and deeper meanings. Perhaps slowing down is the point. Why let life pass by too fast? Why let a poem?

Last, the ending line cuts off the continuation of this form. Perhaps this is intentional: the final line is actually a final and unfinished couplet, signifying the speaker’s own sense of incompleteness while staring at the paradoxes of life.

4. How to Read Poetry: Bringing it All Together

Let me review how I analyzed this poem so far:

- First, I did a slow, careful read of the poem, taking note of important literary devices and color-coding them for analysis.

- Second, I looked for connections between the different literary devices, searching for unifying threads and ideas presented throughout the poem.

- Third, I took note of surprising language―in this case, I focused solely on verbs, but all parts of speech present possibilities.

- Fourth, I looked at how the word choice above reinforces the central ideas presented from the figurative language.

- Finally, I took note of how the poem’s structure contributed further to the poem’s meaning.

Now, we’re finally coming towards a complete understanding of this poem. It’s a beautifully complex patchwork of life’s internal contradictions, ending on a note of continuation and resilience. As humans swept into the mysterious currents of life, we can’t expect to understand the speaker entirely, but we’ve gained a certain small window into his soul.

Moving Toward Reading Poetry Like a Poet

All this analysis for one poem? Well, that’s the wonderful thing about poetry: good poetry packs more meaning, richness, and humanity per word than any other use of language. It truly is the cheesecake of speech.

Good poetry packs more meaning, richness, and humanity per word than any other use of language. It’s the cheesecake of speech.

Looking at each of the steps we’ve examined and how they build upon each other, you may find that they present different ideas for your own work. The following bits of analysis seem like ideas that can be replicated in different poems:

- The use of couplets to build tension.

- Ending the poem on strong nouns and verbs.

- Leaving a last stanza unfinished to reflect incompleteness.

- Juxtaposing unlike images in separate stanzas.

- The poem’s pacing asks the reader to slow down and reflect, despite using enjambment and other fast-pacing techniques.

And that’s just stuff that I picked up on! By contrast, you might find yourself inspired by Vuong’s brief use of dialogue, his interplay of the physical and conceptual, or his object-based storytelling. Find what inspires you, and run with it.

Closing Thoughts

Poetry is one of those great human inventions that takes a lifetime to master. Reading it is hard enough; how do people write it?

The key is to keep writing. Whether you write by yourself or in a poetry workshop, the most important thing you can have as a poet is diligence. Keep practicing, keep observing what works in poetry, and keep experimenting with language and form. The world needs more poetry!

What a wonderful breakdown of a topic that should be very useful to a lot of people. I’ve studied poetry intensively and have never seen such a well put together overview.

Great article. I love Ocean Vuong. I write and ;publish poetry regularly. I have a third book coming out in February from Wapshott Press called Three Soul-Makers: Poems to Bring Us together. I love studying the decisions poet’s make in their pieces, the economy of words, the many line break choices. I wish you could get this article out to EVERYONE in the universe. So many people are intimidated by poetry or have only their tortured high school English assignments to refer back to. I’ve even tried to rename poetry just to take this stigma away. I have an MFA in Creative Writing but never took any poetry classes, so I’m self-taught. I subscribe to Poets.org and Rattle Poetry. It’s a wonderful art form. I’m also a singer, so I usually can tell melodically how many words a line or a stanza needs to feel complete. I’m gonna share this with my writing friends. Happy, safe Holidays…Mary Kennedy Eastham

Very nice article with plenty of information. Want more information on thought provoking poetic parameters which make poetry a creative.

I’m planning an introductory poetry course. Your article will be a fabulous resource!

Thank you, Katherine 🙂 – we’d love to see it when it’s ready!

This article was so fun to read & easy to follow. It has definitely sparked inspiration for me to continue writing! Thank you

A brilliant vial of vitamins and minerals for our poetic mind. Thanks a lot .

Terrific piece, Sean. Especially intrigued by the color-coding technique for analyzing a poem. Very helpful!

Thank you for this analysis. I appreciate your sharing this approach because it makes poems I’ve felt impenetrable (like this one on first readings) become more approachable.