A free verse poem is a poem that doesn’t rely on any particular form, meter, or rhyme scheme, yet still conveys powerful feelings and ideas. Rather than letting a certain structure define the poem, the poet lets the poem structure itself through the interplay of language, sound, and literary devices.

Wait a minute—poetry doesn’t have to have a form? Well, all poems have forms, but a free verse poem doesn’t have to have a fixed form. While schools expose students to highly formal poetry (sonnets, villanelles, haikus, and the like), there are countless free verse poem examples that are just as delightful and intriguing.

So, what is a free verse poem? What is the difference between blank verse vs. free verse? And where can I learn how to write a free verse poem? Right here—let’s define the form, explore some famous free verse poems, and look at how to write one.

Contents

What is a Free Verse Poem?

Before we look at a free verse poem definition, it’s important to understand what free verse poems aren’t. Characteristics of free verse poetry include a lack of form, meter, and rhyme scheme, which we will expand upon shortly. But first, if you don’t know what form, meter, or rhyme are, read below.

Characteristics of free verse poetry include a lack of form, meter, and rhyme scheme.

When discussing form in poetry, there are a few different concepts to know:

Free Verse Poetry Does Not Have: Meter

Meter refers to the pattern of syllabic stress in the poem. A syllable can be either stressed or unstressed, depending on how each syllable is emphasized.

Take, for example, the word “bombard.” Here, the second syllable is stressed, because you put emphasis on the word like this: “bom•bard.”

This pattern of unstressed-stressed is called an iamb; in an iambic poem, a line of poetry roughly follows this pattern, word after word and line after line. Each line, also, will usually include the same number of iambs. Other metrical patterns include the trochee, anapest, and dactyl.

If you’re interested in meter, read more about it here:

Free Verse Poetry Does Not Have: Rhyme Scheme

A rhyme scheme is a pattern of rhyming words, typically at the end of each line of poetry. A simple rhyme scheme is an “ABAB” rhyme scheme, in which the 1st line rhymes with the 3rd, and the 2nd line rhymes with the fourth.

Here’s an example of that rhyme scheme, from the poem “A Psalm of Life” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow:

Example poetry with a rhyme scheme:

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!—

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

Rhyme schemes can be much more complicated than this, and there are also such things as slant rhymes and internal rhymes. When it comes to poetry form, however, a rhyme scheme involves perfect rhymes occurring at the ends of lines.

Article continues below…

Poetry Writing Courses We Think You'll Love

We've hand-picked these courses to help you flourish as a writer.

Warp and Weft: Weaving Free Verse Poetry from Life

Weave everyday events into deftly-written free verse poems in this generative, creativity-centered poetry workshop.

Find Out MoreOr click below to view all courses.

See CoursesArticle continues…

Free Verse Poetry Does Not Have: Fixed Form

Form combines the elements of rhyme and meter, adding additional requirements of length and lineation.

A traditional Italian Sonnet, for example, has the following requirements:

Length: 14 lines in 2 stanzas, an octet and a sestet.

Meter: Iambic Pentameter (5 iambs per line).

Rhyme Scheme: ABBA ABBA CDE CDE. Some variation exists for the rhyme scheme of the last six lines, but the first eight lines are always ABBA.

Learn more about poetry form at our article What is Form in Poetry?

Summing Up: What is a Free Verse Poem?

A free verse poem, also known as a vers libre, is a poem that lacks all of the above. It has no defined meter, no consistent rhyme scheme, and no specified length or formal requirements.

What is a free verse poem? A free verse poem, also known as a vers libre, is a poem that has no defined meter, no consistent rhyme scheme, and no specified length or formal requirements.

Because of this, a free verse poem follows its own internal logic. While the free verse poem has no externally defined form, it does rely on sound, word choice, length, and literary devices to become cogent and compelling.

Characteristics of Free Verse Poetry

What are some characteristics of free verse poetry, especially if it doesn’t use rhyme or meter?

When we get to some free verse poem examples, you’ll see that it’s impossible to organize all free verse poems into one set of traits. However, many poems will have some or most of the following:

Cadence and Flow

Cadence refers to the natural rhythm of the poem, as defined by changes in pitch, sound, and emphasis.

In poems with formal structures, the cadence is shaped by the poem’s length and meter. For example, an iambic poem has a cadence not-so-different from the beating of one’s heart, as the iamb follows a ba•dum, ba•dum, ba•dum, ba•dum pattern.

In free verse poems, cadence is built from the language the poet uses. Poetic devices like euphony, cacophony, and alliteration help develop the poem’s pace and rhythm.

In free verse poems, cadence is built from the language the poet uses.

The end result is the poem’s flow. How does it feel to read the poem? Does it move like the wind? Pulse like a heart? Crash like a wave? Crack like glass?

Form Following Language

In formal poetry, language follows form. The words must be arranged to fit the poem’s metrical patterns, rhyme schemes, and other requirements. Of course, the form aids the meaning of the poem, as the two work together, but the rules of the form cannot be broken (except in very intentional circumstances).

The poem’s line lengths, stanza breaks, internal rhymes, cadence, and overall length are defined by the words that the poet uses.

With free verse poems, the opposite is true: form follows language, like a tailored suit. The poem’s line lengths, stanza breaks, internal rhymes, cadence, and overall length are defined by the words that the poet uses.

This isn’t to say that free verse poems are easier to write than formal poems, nor are they intrinsically “better” or “worse.” The end result is the same: a piece of literature charged with imagery, emotion, language, meaning.

Non-Uniform Lines and Stanzas

One of the more obvious characteristics of free verse poetry is its lack of uniform line- and stanza-lengths.

In the free verse poem, lines and stanzas do not need to be uniform.

In a formal poem, the lines will be a similar length to each other, and each stanza will carry a predefined set of lines.

In the free verse poem, lines and stanzas do not need to be uniform. One line can have 2 words and the next can have 12; one stanza can have 8 lines and the next can have 1. This freedom of lineation allows the poet to let language define the poem’s structure.

Experiments With Space

Because free verse poems have no set length, they can play with space on the page in a way that formal poems can’t.

Because free verse poems have no set length, they can play with space on the page in a way that formal poems can’t.

What does that mean? Here’s are three free verse poem examples that take up the full page, rather than just sticking to left-flush, uniform lines:

- “Deconstruction: Onion” by Kenji C. Liu

- “Rules at the Juan Marcos Huelga School (Even the Unspoken Ones)” by Lupe Mendez

- “Swan and Shadow” by John Hollander

As you can see in each example, the poet experiments with page space and lineation in a way that adds to the poem’s meaning.

Prosaic Qualities

Because formal poetry sticks to a particular form, those poems are always written “in verse.” Free verse poems, on the other hand, can borrow from the qualities of prose, using straightforward language and sentence structure to reinforce poetic ideas.

Free verse poems can borrow from the qualities of prose, using straightforward language and sentence structure to reinforce poetic ideas.

This is differentl from the prose poem, which is a poem written in sentences and paragraphs, rather than lines and stanzas. the prose poem is its own unique form, but free verse poems can borrow qualities from the prose poem, as well as from many other forms of poetry.

Concise Imagery

It is important for formless poems, especially short free verse poems, to build concise, vivid imagery. A poem might not impact the reader if the reader cannot visualize the poem, and without form to rely on, the free verse poem must compensate through imagery.

Free verse is often used by poets to create meaning from chaos, letting language develop new forms, ideas, and images.

Take “The Red Wheelbarrow” by William Carlos Williams, a concise but powerful example of short free verse poems. The poem’s meaning isn’t clear, but it is provocative: what, exactly, relies on the wheelbarrow? Why does its juxtaposition to the chickens matter?

Despite its brevity, Williams’ poem has a metaphysical element to it, pushing the reader to question and define the image further. It is a poem built upon the interplay of poet and reader, using formlessness to create its own meaning.

Free verse is often used by poets to do exactly that: create meaning from seeming chaos, letting language develop new forms, ideas, images.

Free Verse vs. Blank Verse

You may have heard of the poetic form “blank verse,” which sounds pretty similar to “free verse.” Before we look at more free verse poem examples, let’s clarify the difference between free verse vs. blank verse.

Unlike free verse poems, blank verse does require a specific type of meter, and each line has to have the same number of feet.

A blank verse poem is a specific poetry form. It is written with a specific metrical form: many blank verse poems are written in iambic pentameter, which means each line of poetry has five iambs. However, other forms exist as well, such as trochaic blank verse or dactylic blank verse.

Like free verse poems, blank verse poems have no defined length—they can be as short as 10 lines or as long as 10,000. Many poets have used the blank verse form to write soliloquies, monologues, and epics. Additionally, blank verse does not require a specific rhyme scheme.

Unlike free verse poems, blank verse does require a specific type of meter, and each line has to have the same number of feet.

Another way to think about the difference between free verse vs. blank verse is that blank verse is the halfway point between formal poetry and free verse: it doesn’t have a rhyme scheme or predefined length, but it does have meter.

Free Verse Poem Examples

As you’ll see in the below free verse poem examples, the free verse form challenges what a poem can truly become. For each of these short free verse poems, read each poem like a poet, taking note of how each poem uses language to scaffold form.

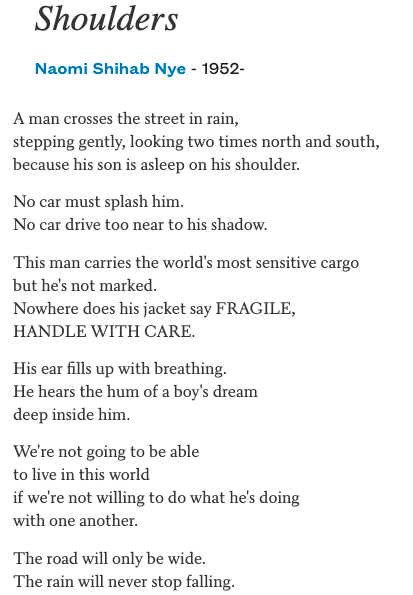

“Shoulders” by Naomi Shihab Nye

Found here in the Academy of American Poets.

In this simple free verse poem, Naomi Shihab Nye comes to a powerful conclusion from a simple observation. In the poem, a man crosses the street while carrying his sleeping son. So as not to disturb his son’s sleep, the man must cross while keeping his son away from the light and noise and splash of the car.

Nye’s poem shows us a beautiful moment of tenderness. She notes that the boy isn’t marked “FRAGILE”—nothing about the boy begs his father’s tenderness, but he offers it nonetheless.

The last two stanzas are the most powerful. Nye observes that the world is much like this rainy road—the road will always be wide and rainy, and the world will always be difficult to live in. How can we expect to survive if we don’t treat each other with this same tenderness, noting what’s “FRAGILE” in each of our delicate, beautiful lives?

“The Heaven” by Franz Wright

I lived as a monster, my only

hope is to die like a child.

In the otherwise vacant

and seemingly ceilingless

vastness of a snowlit Boston

church, a voice

said: I

can do that

if you ask me, I will do it

for you.

Take note of the gorgeous lyricism in this piece: you can hear the phrase “seemingly ceilingless / vastness” bounce off the walls like they’re echoing in that snowlit Boston church. With this image juxtaposed against the first line’s monstrosity, the poem evokes both Heaven and Hell, begging for absolution as pure as a child’s innocence.

“First Memory” by Louise Glück

to revenge myself

against my father, not

for what he was—

for what I was: from the beginning of time,

in childhood, I thought

that pain meant

I was not loved.

It meant I loved.

This poem untangles the different kinds of pain that the speaker felt from childhood neglect. The speaker believed that the endurance of that pain, the reason it stung years into her adulthood, was because she was not loved the way she needed. This may still be true, but the core of her pain is that she loved her father, and this love keeps the wound fresh.

Short free verse poems often rely on simple juxtapositions or binaries, dismantling the poet’s ways of thinking through sharp, concise language.

“little prayer” by Danez Smith

Found here in the Academy of American Poets.

let him find honey

where there was once a slaughter

let him enter the lion’s cage

& find a field of lilacs

let this be the healing

& if not let it be

This free verse poem relies on the unexpected. Where the speaker expects slaughter and ruin, they hope someone will find honey, lilacs, and healing. These terse juxtapositions create some surprising imagery, as the reader imagines honey doused over a killing floor, or flowers in a lion’s cage.

By titling the poem “little prayer” (in undercase letters, no less), Smith’s poem is both a hope and a dare, petitioning whatever higher power there is to heal what might seem unhealable.

“On a Train” by Wendy Cope

Found here in The Poetry Archive.

The book I’ve been reading

rests on my knee. You sleep.

It’s beautiful out there—

fields, little lakes and winter trees

in February sunlight,

every car park a shining mosaic.

Long, radiant minutes,

your hand in my hand,

still warm, still warm.

Some poems don’t need to have deeper meanings; they can simply exist and find loveliness in existence. Wendy Cope’s free verse poem “On a Train” does exactly that. By reminiscing on a cold Winter’s afternoon and finding warmth in the unexpected, the speaker reminds us of beauty in the everyday, not least when next to the one you love.

If you’re interested in writing short poetry, take a look at our article Examples of Short Poems and How to Write Them.

Here are some longer free verse poem examples that might also interest you:

- “Dear Proofreader” by David Hernandez

- Pluto Shits on the Universe Fatimah Asghar

- I Wake Early by Jane Hirshfield

How to Write a Free Verse Poem

Now, let’s take a look at how to write a free verse poem. Because free verse poems have unlimited possibilities in length, formatting, and intention, there is no singular way to write any piece. After all, free verse is often used by poets to generate form from meaning, so if there was one standard method on how to write a free verse poem, these poems would be a lot less variegated and interesting.

Nonetheless, you can rely on the following 5 tips to generate your poem, paying close attention to the characteristics of free verse poetry as we described earlier.

1. Start with a mental image, emotion, or idea

The best poetry doesn’t spell out an idea in plain language, it illustrates that idea through vivid imagery.

The best poetry doesn’t spell out an idea in plain language, it illustrates that idea through vivid imagery.

Consider the above free verse poem examples. Naomi Shihab Nye illustrates the careless world as a wide, rainy road; Danez Smith illustrates healing as lilacs in a tiger’s cage. These simple images create powerful metaphors, showing the reader different ways to view the world.

In your own poetry, start with the ideas and images you want to form the poem. These items don’t have to start your piece, but they will likely form the core of what you write, giving shape and substance to your free verse poem.

Learn more about starting a poem here:

2. Follow the voice in your heart

One of the joys—and challenges—of writing free verse poetry is the limitlessness of the form. Rather than fitting your feelings into predefined structures, your feelings structure the poem itself. This can be hugely liberating, and also hugely mortifying.

Free verse is often used by poets to give form to their feelings. As such, you should try to do the same, and you can accomplish this by following the voice in your heart.

What does that mean? It means speaking openly and honestly on the page, turning off the inner critic and getting the words down first.

You don’t even have to start with poetry: you can write a sort of prose poem and edit later. Questions of form, like line breaks, stanza breaks, indentation, and flow, can arise after you’ve put the word down. That’s for your brain—but first, write from the heart, and do so without any self-editing.

3. End lines on concrete nouns and verbs

An enduring rule of all poetry writing is to end lines on concrete nouns and verbs. By concrete, we mean words that are visual—you can visualize the word “brick,” for example, but you can’t visualize the word “neologism.”

An enduring rule of all poetry writing is to end lines on concrete nouns and verbs.

Generally, it’s best not to end lines on other parts of speech. Sometimes you can end a line on an adjective or even an adverb, but pronouns, articles, prepositions, being verbs, and conjunctions are rarely useful end words.

End words clue the reader towards what is most important in the line, especially because line breaks and stanza breaks emphasize those end words.

Of course, rules are made to be broken, just break them skillfully. For example, in the free verse poem “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks, most lines end on the preposition “we” to emphasize the lack of individualism among the poem’s subject—truant school boys.

4. Play with line breaks

The best line breaks accomplish two things. First, they emphasize the most important word or phrase in the line, usually highlighting concrete imagery. Second, they add pauses in the flow of the words, allowing certain ideas to stick with the reader and creating the poem’s cadence.

The best line breaks accomplish two things. First, they emphasize the most important word or phrase in the line, usually highlighting concrete imagery. Second, they add pauses in the flow of the words, allowing certain ideas to stick with the reader and creating the poem’s cadence.

Looking deeper, there are two types of line breaks: end-stopped lines and enjambed lines. An end-stopped line is when the line breaks after a period, semicolon, em dash, or colon. This can also occur when a line ends with a comma or the completion of a phrase, where a natural pause would exist anyway. End-stopped lines emphasize the completeness of an idea.

Enjambed lines are lines where a line break interrupts an unfinished thought. These lines usually do not end in punctuation, and they emphasize the continuity of a thought, often juxtaposing different ideas in the same lines.

Since experiments with space are one of the characteristics of free verse poetry, poets can further play with line breaks by indenting them across the page, writing lines of poetry in center-flush or right-flush, and including indents and lacunas in the text.

The best way to experiment with line breaks is to observe how other poets do it. Take a look at the free verse poem examples we provided, including the longer-form poems we linked to. Observe how the line breaks, stanza breaks, and use of page space affects how you read and interpret the poem, and incorporate those experiments into your own work.

5. Edit for flow, clarity, and impact

If you plan on publishing your free verse poem, consider edits for flow, clarity, and impact.

Make sure the poem’s cadence flows where you want it to, and breaks where you want it to break as well. Make sure each image is crisp, understandable, and relates clearly to the poem’s topic. Use line breaks to highlight important images, and use stanzas to organize and juxtapose those images.

Finally, consider how the poem starts and ends. Does the poem end different from how it began? Does each line build upon the previous line’s ideas? Does the poem’s ending inspire, educate, provoke, excite, or chill the reader?

Why Write Free Verse Poems?

Free verse is often used by poets to give form to feeling, letting language dictate the terms of the poem itself.

Free verse is often used by poets to give form to feeling, letting language dictate the terms of the poem itself. Formal poetry, on the other hand, is used by poets to challenge their creativity, as the task of fitting words into form, making those words compelling, and crafting an impactful poem is often just as challenging.

Many poetry forms have a certain kind of history, and often dwell on similar topics. Many sonnets and ghazals focus on love, for example. Nonetheless, there is no particular reason to prioritize one poetry form over another: at the end of the day, both formal and free verse poems provide unique creative opportunities.

So, which should you write? Pay close attention to your own needs as a poet. If you have a lot of feelings that you want to explore on the page, you might be better starting off with free verse or even prose poetry. If you have a clearly defined topic in mind and want to challenge your word choice, formal poetry might give you the creative outlet you need.

And remember, nothing is final on the page. You can write a free verse poem and edit it into a sestina or villanelle; you can write a cinquain or a contrapuntal, then edit it into free verse. The page is yours to play with!

Experiment with Poetry Forms at Writers.com

Want to learn more about free verse poems and poetry forms? The courses at Writers.com can help! Take a look at our upcoming poetry courses, where you’ll study the craft, process, and techniques of poetry writing. We hope to see you there!

Your page is giving me hope, literally

Exact information I was looking for.

Thanks❤️

I have learnt a lot. Thank you for this writeup. As an aspiring poet, I will be able to do better with the knowledge I have gained from here.

I savor the order in which you shared this information. Never seen it put quite this way. Very interesting indeed. The info obtained here, I consider an asset, and thank you very much. I love trying to write poetry. I did get one book of poetry published in my younger years, When God Speaks, Write! I wish I would have had this information back then. May God Bless you.

Good examples

Highly informative & helpful. I’d resisted writing free verse until very recently, fearing that I’d just produce word spew. This article has provided some guidelines. Thank you.

Very helpful to me. I’ll re-read not sure I’ve soaked in all the information.

I write mostly in free verse and I love the freedom when especially composing it’s music.For example I do use rhyme but on in a set rhyme scheme but rather anywhere in a line.

I haven’t written many poems but all those I have written are all free verse poems and I love writing free verse poem by going through the speech I got much more clarity and the areas where I lacked I think it’s really very useful for me…

Thank you for giving this much information!!

They are really very useful!!