Few literary genres allow for experimentation quite as easily as prose poetry. Blending the techniques of prose with the emotion and lyricism of poetry, the best prose poems uncover subconscious thought with searing originality. Poets looking to break free from form, and prose writers seeking new means of expression, will absolutely find creative freedom in prose poetry.

So, what is a prose poem? What differentiates the genre from the lyric essay? And why might you write prose poetry?

This article discusses the history of the form, with prose poetry examples and a discussion of how to write a prose poem. Let’s explore the features of prose poetry and the techniques of this experimental, expanding genre.

Prose Poetry: Contents

Prose Poetry Definition

Which of us, in his ambitious moments, has not dreamed of the miracle of a poetic prose, musical, without rhythm and without rhyme, supple enough and rugged enough to adapt itself to the lyrical impulses of the soul, the undulations of reverie, the jibes of consciousness? —Baudelaire, Paris Spleen, ix

What is a prose poem? It can be difficult to define, as the genre borrows heavily from different genres, and its definition changes within different periods of literary history. Additionally, many writers and critics have differing opinions about the form, making it harder to craft an objective prose poetry definition.

Article continues below…

Prose Poetry Writing Courses We Think You'll Love

We've hand-picked these courses to help you flourish as a writer.

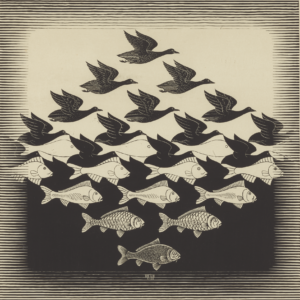

Both Fish and Fowl: The Prose Poem

A successful prose poem reads like a magic trick. Learn how to wield the powers of poetry in the context...

Find Out More

Poetic Prose & the Prose Poem

Explore the border between prose poetry and flash fiction. For writers of fiction, poetry, essay and memoir.

Find Out More

Writing Poetic Memoir: Flash or Prose Poems

Begin crafting a memoir in 8 mini chapters of poetry, prose poetry, or flash. Shape vivid, lyrical narratives that shine...

Find Out MoreOr click below to view all courses.

See CoursesArticle continues…

4 Prose Poetry Definitions from Prompt Book

Our wonderful instructor, Barbara Henning, tackles these different prose poetry definitions in her writing guide Prompt Book. Here’s an excerpt from her book that covers some different interpretations of prose poetry.

An excerpt from Prompt Book:

If you start searching around in literary dictionaries, you will find a variety of definitions, such as:

(1) Martin Gray writes, “Short work of POETIC PROSE, resembling a poem because of its ornate language and imagery, because it stands on its own, and lacks narrative: like a LYRIC poem but is not subjected to the patterning of METRE.”

(2) An entry in the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry And Poetics: “A composition able to have any or all features of the lyric except that it is put on the page—though not conceived of—as prose. It differs from poetic prose in that it is short and compact, from free verse in that it has no line breaks, from a short prose passage in that it has, usually, more pronounced rhythm, sonorous effects, imagery, and density of expression. It may contain even inner rhyme and metral runs. Its length, generally, is from half a page (one or two paragraphs) to three or four pages, i.e., that of the average lyrical poem.

If it is any longer, the tensions and impact are forfeited, and it becomes—more or less poetic prose. The term “prose poem” has been applied irresponsibly to anything from the Bible to a novel by Faulkner, but should be used only to designate a highly conscious (sometimes even self-conscious) art form.” (John Simon)

(3) In one of the early prose poem anthologies, Michael Benedkt writes, “It is a genre of poetry, self consciously written in prose, and characterized by the intense use of virtually all the devices of poetry.. . . The sole exception . . . we would say, the line break.”

(4) A contemporary critic Stephen Fredman—who has written extensively about language poetry—calls it “poet’s prose.” He objects to the above definitions of the prose poem because they rely too heavily on Baudelaire’s description of a prose poem. The language poets were often critical of lyrical narrative-oriented poems. Fredman quotes David Antin:

“‘Prose’ is the name for a kind of notational style. It’s a way of making language look responsible. You’ve got justified margins, capital letters to begin graphemic strings which, when they are concluded by periods, are called sentences, indented sentences that mark off blocks of sentences that you call paragraphs. This notational apparatus is intended to add probity to that wildly irresponsible, occasionally illuminating and usually playful system called language.”

Novels may be written in ‘prose’; but in the beginning no books were written in prose, they were printed in prose, because ‘prose’ conveys an illusion of a common-sensical logical order.

Without writing, we had the sound of our words and poetic language to help us remember; then we had lines perhaps to help us hear the rhythm of our spoken voice. All aids to memory. Sentences and paragraphs are borders for organizing thoughts and pauses between thoughts.

I think of a prose poem as simply a poem written in sentences and paragraphs, rather than lines. It can be narrative. It can be dramatic. It can be lyrical. It can be scientific. It can be experimental. It can be so many things, but if the language and structure stand out, rather than the information, description, dialogue, plot, then I think of it as a poem. “Poetic prose” might be a little closer to language that explains or elaborates, unless it is fracturing and experimenting with the language of explanation. But, of course, this can be endlessly debated.

If you want to read a long thoughtful exploration on the definition of a prose poem, I suggest reading Michael Deville’s book, The American Prose Poem.

Summing Up: What is a Prose Poem?

In short, there’s no singular prose poetry definition, and many theorists disagree on the exact confines of the genres. However, most definitions agree on the following features of prose poetry:

Prose poetry is:

- Short—generally no longer than 4 pages, and sometimes only 1-3 brief paragraphs.

- Unconfined—prose poetry has no line breaks and is unaffected by the margins of the page.

- Sonic—a prose poem may rely on rhythm and internal rhyme, and often has a certain musicality (or, even, cacophony).

- Concise—every word matters and builds tension.

- Experimental—the writer must rely completely on word choice, since prose poetry eschews the bounds of poetry forms and traditions.

Prose Poetry Examples

Let’s take a look at some prose poetry examples. The best prose poems incorporate the above features of prose poetry, and they also delve deeper into the speaker’s psyche, revealing powerful thoughts and feelings. Consider these 4 examples of prose poetry.

1. After the War by Heidi Howell

Originally published at Eastern Iowa Review.

After the War

- not remembering she thinks it. whenever there is a desire, a pause. she thinks it slowly blue, broken but not stars. (it can be more or less). something like a curve. or an after. she thinks it with or without the daughter. before or after the distance. a field and there isn’t any wind. finally, she has not seen it. she just stands and thinks it.

- the breath waits to happen. it pretends a separate movement. an open. a close. to refuse it is only wet feet. clothing. around the rain and after hold your hands up in the air. clasp it. asking. this always in the distance. and you not walking there.

- “i tell you not lingering what is the intimate. departing she has watched and stepped through. over them stumbling like the unexpected stick or fold. high. near. let fall. always a gap and she was believing its benevolence. holding that space and feeling it filled. everything happened. now. she will not deny or suspend.”

Let’s explore how “After the War” fits into our prose poetry definition.

- Short: The speaker explores the dissonance of thought in three brief paragraphs.

- Unconfined: There are no intentional line breaks or metrical patterns.

- Sonic: there are many examples of alliteration, such as “blue, broken but,” “believing its benevolence,” and “feeling it filled.” Additionally, the patterning of short and long sentences creates an evolving rhythm, like water gushing downstream.

- Concise: The sounds and sentence patterns build tension, while the writing explores the confines of a dangerous thought.

- Experimental: This prose poem explores a thought without ever speaking that thought. We feel the speaker’s emotions without needing to know exactly what’s on her mind. The writing also experiments with sentence structures, and it eschews the use of capital letters.

2. The Not Knowing is Most Intimate by Ilana Gustafson

Originally published in the writers.com Community Journal.

The Not Knowing is Most Intimate

The dharma teacher’s wife is leaving him after forty-nine years of marriage. I think of him as you and I lay under the trees, away from the rest of the group. You ask me to identify birds. Acorn woodpecker. Rock pigeon. Red-tailed hawk. But you knew that one. My parents celebrate fifty years this month. I prefer the company of people who aren’t afraid to admit they don’t know a crow from a raven. Not knowing is most intimate. Not once has anyone at this party asked me what I do. I was prepared to answer honestly. “I hear animals calling through my body in the middle of the night,” and ponder how long they will keep talking to me. How long did his wife wish to leave? Oriole. They make these elaborate basket nests. I google a picture to show you. You drift off into the screen. Was it sudden? I am glad he is a Zen master. Preparation for this unfathomable fall into the intimate unknown. Life without his companion. That’s a raven, not a crow. The ground, a grassy little teeter-totter.

Let’s explore how “The Not Knowing is Most Intimate” fits into our prose poetry definition.

- Short: Multiple ideas are presented in one paragraph, exploring the intimacy and humanness of simply not knowing.

- Unconfined: There are no intentional line breaks or metrical patterns.

- Sonic: This prose poem alternates between short and long sentences. Additionally, it alternates between declarative sentences, questions, and dialogue, keeping the pace fresh and interesting.

- Concise: These three narratives could easily take up pages and pages of narrative. Instead, they’ve been condensed in a way that the reader can make connections and glean insight, without having that insight stated explicitly.

- Experimental: This prose poem uses a narrative technique called braiding, interweaving multiple storylines into a single cogent story. It is common for prose poetry to borrow techniques from other genres.

3. Be Drunk by Charles Baudelaire

Reproduced from Poets.org. Baudelaire was one of the first Western writers to embrace the prose poetry form.

Be Drunk

You have to be always drunk. That’s all there is to it—it’s the only way. So as not to feel the horrible burden of time that breaks your back and bends you to the earth, you have to be continually drunk.

But on what? Wine, poetry or virtue, as you wish. But be drunk.

And if sometimes, on the steps of a palace or the green grass of a ditch, in the mournful solitude of your room, you wake again, drunkenness already diminishing or gone, ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, everything that is flying, everything that is groaning, everything that is rolling, everything that is singing, everything that is speaking. . . ask what time it is and wind, wave, star, bird, clock will answer you: “It is time to be drunk! So as not to be the martyred slaves of time, be drunk, be continually drunk! On wine, on poetry or on virtue as you wish.”

Let’s explore how “Be Drunk” fits into our prose poetry definition.

- Short: This prose poem is written in three brief paragraphs.

- Unconfined: There are no intentional line breaks or metrical patterns.

- Sonic: There are some great examples of alliteration, such as “burden of time that breaks your back and bends you,” as well as “drunkenness already diminishing.”

- Concise: Baudelaire captures a philosophy of life in three simple paragraphs. It’s not about alcoholism or chemical intoxication: it’s about being inebriated with life itself, much like all of nature seems to be.

- Experimental: The last paragraph is built with a single sentence, which emulates the intensity and ecstasy of life itself. Additionally, Baudelaire was highly experimental for his time, as most poetry still conformed to the strictness of meter and rhyme schemes.

4. Stinging, or Conversation with a Pin by Stephanie Trenchard

Originally published in the Writers.com Community Journal.

Stinging, or Conversation with a Pin

Stinging me—that pin. Caressing you—this curve. Imagine me that night forgetting you this morning. Lulling me, an oversight, goodnight. Alarming you under dark, rough morning. Reminding me of pain, forgetting you for pleasure. Shaming me for denying. Accepting you not believing. Always in a rush, never out of time. Lazy busy me. Enterprising deliberate you. Let it lay, a pin in the plush. Pick it up, this orb of concrete. Sleepy, pin pokes as pins do. Awake, orb rolls unlike orbs. Sharp unknown in the rug, smooth known under a bed, a thing that hurts remains untouched

Let’s explore how “Stinging, or Conversation with a Pin” fits into our prose poetry definition.

- Short: This prose poem is only a paragraph in length.

- Unconfined: There are no intentional line breaks or metrical patterns.

- Sonic: There’s a lot of internal rhyme in this piece, with consecutive “ing,” “ight,” and “zee” sounds.

- Concise: In one paragraph, this prose poem establishes a dialogue between the pin and the curve, with each symbolizing one side of a dysfunctional relationship.

- Experimental: Like other prose poetry examples, this piece relies on specific poetry techniques—namely, juxtaposition and symbolism. Yet this piece is also structured like dialogue, which is more common in prose. By putting the pin and the curve in conversation and letting each item represent one half of a doomed relationship, the speaker traces the psyche of someone whose love won’t let them thrive.

Where to Find and Submit Prose Poetry Online

A handful of literary journals routinely publish prose poems. If you’re looking for more prose poetry examples, or if you’d like to publish a prose poem yourself, check out these journals:

How to Write a Prose Poem: Tips and Strategies

In many ways, the act of writing prose poetry is freeing. Rather than deliberating over line breaks, rhyme schemes, or “sounding poetic,” the prose poet merely needs to write prose, poetically.

Nonetheless, there are a few strategies you can use to write polished, emotive prose poetry. Here’s 5 tips on how to write a prose poem.

1. Write Stream of Consciousness

Stream of consciousness is a writing technique in which the writer’s thoughts flow unfiltered onto the page. It’s a tough technique to master: the writer has to focus on setting each thought on the page, without editing or omitting anything. This practice, also known as “First Thought, Best Thought,” is a facet of the Mindfulness Writing Method.

Writing stream of consciousness allows the writer to reveal crucial aspects of their psyche. Refer back to John Simon’s prose poetry definition, which argues that the genre is “a highly conscious (even self-conscious) art form.” Stream of consciousness requires practice and research, but with mastery, you can easily identify threads of thought that lend themselves to prose poems.

2. Use Poetic Devices

Although prose poetry doesn’t use meter or rhyme schemes, it does rely heavily on poetic devices. Sound devices (like alliteration, consonance, euphony, internal rhyme) and literary devices (like metaphor, symbolism, juxtaposition, anaphora) help create the experience of the prose poem, both sonic and emotive.

Just like stream of consciousness, the use of poetic devices takes time to master. However, many poetic devices emerge on their own accord, without intervention from the writer. Many images can be imbued with symbolic meaning simply by existing, and you might also benefit from starting with a writing prompt.

Simply put: use concrete images, play with sound, and write honestly. You might be surprised by the deeper meaning that emerges.

3. Play With Punctuation and Sentence Structure

In addition to sound devices, punctuation and sentence structure can improve the experience of the prose poem.

Punctuation greatly affects readability. If your sentences contain mostly commas and periods, they’ll be read as complete, authoritative thoughts. Sentences that contain colons and semicolons might: meander; flit between different thoughts and ideas; create moving, long-winded experiences; or even combine multiple ideas into one long, comprehensive sentence. Finally, the use of em-dashes—like in “With a Bang” by Barbara Henning—can highlight the poem’s stream of consciousness—moving in and out of thoughts like bees flitting through flowers.

Sentence structure also affects readability. Short sentences are crisp. They demonstrate authority and simplicity. Long sentences, on the other hand, can wander all over the page, creating vivid soundscapes and haunting juxtapositions—as well as hard-to-follow ideas or intricately constructed emotions.

Both prose writers and poets must pay attention to punctuation and sentence structure. However, these elements are especially important to prose poetry, as they seek to emulate the writer’s own thoughts and feelings. The elements of grammar aren’t just mechanical, they’re essential to creating the prose poetry experience.

4. Focus on Musicality

What happens when you make your prose sing? Because the prose poem defies conventional forms and structures, it can also defy conventional meanings and logics. The daring prose poet might try to write towards something sonorous, imbuing their work with musicality before editing for clarity.

What does this mean? It means letting the words take you where they want to go. It means musical sentences. Words with rhythm and cadence. Language that prioritizes sound over meaning; language that makes meaning through sound.

In other words, try writing a prose poem using words that you love just because you love them. You can always edit to make the prose poem make sense later. For writing, just play with language. Use words as your sandbox. If you love the sound of words like “zephyrous” and “susurration,” or if you love onomatopoeias like “kaboom” and “clackety-clack,” use them even if they don’t make perfect sense. Prose poets love the sounds of words, and a good prose poem can create an experience solely out of sound.

5. Edit for Clarity

You might find that, after reading your stream of consciousness, your writing doesn’t make much sense. Sometimes, this is perfectly fine—prose poetry is often about creating a literary experience, evoking emotions without obvious logic.

At the same time, if the writing feels too obscure or incomprehensible, it’s worth editing for clarity and omitting needless words.

To be clear: your edits should focus mostly on clarity. You can clean up your sentences, add some sonic devices, and alter punctuation.

However, you shouldn’t focus on adding more words or changing the poem’s meaning. Such interference can make the work more confusing and obscure. The best prose poems act as mirrors of the heart; over-editing merely streaks the glass.

The best prose poems act as mirrors of the heart; over-editing merely streaks the glass.

Learn How to Write a Prose Poem in our Prose Poetry Course!

Looking for more prose poetry examples and tips? Barbara Henning’s course Poetic Prose: The Prose Poem helps writers experiment their way through prose poetry.

The prompts in Barbara’s class direct the student to look at their spoken and inner language as ever available material from which to make art. The assignments, backgrounds and prose poetry examples offered provide an introduction to the prose poem and to some of the poetic movements in modern and contemporary off-center poetry, such as imagism, surrealism, objectivism, the New York School, Language writing, etc. The prompts are designed to expand a poet’s sense of voice and form, offering new constraints and approaches. If you are a prose writer, the assignments may help you work on sentence style and narrative structures.

Learn the form’s history and techniques, and create moving works of poetic prose with Barbara’s prompts and assignments. You can also gain extra feedback on your work through the Writers.com Community. We hope to see you there!

I would love to take your class, but the tie is conflicting with a classIm taking now. Please let me know when you will give this class again

Hi Svetlana, thanks for your message! If the November 10th session of Poetic Prose doesn’t work for you, the next session will be offered on March 9th, 2022. Feel free to email writers@writers.com with any questions about this. Much appreciated!

I thoroughly enjoyed this detailed review of prose poetry. Thank you for sharing!

Thank you for the explanation, This is truly mysterious. The form makes more sense now.

Wow! This was very enlightening and super fun.. Thank you, so much for such a well detailed article. It’s as poetic as the topic discussed.

[…] Today’s prompt from NaPoWriMo asks for a surreal prose poem. For reference, this link features the confines of what is a prose poem. […]

Very informative! Thank you.

Wow! You just helped me understand my own way of Writing! This makes totally sense to me and I am much better eqipped now to edit my texts and understand their structure and coherence! Thank you so much!