Poetry can powerfully express human emotion, unpacking (or sometimes complicating) the complexities of our feelings and experiences. When a poem dwells on loss or lamentation, it is known as an elegy.

When a poem dwells on loss or lamentation, it is known as an elegy.

Elegiac poetry is a millennia-old tradition, and examples of elegy poems predate Ancient Greece, when the term first came into use. Poets looking to explore loss, death, or serious topics in their work may want to learn how to write an elegy poem.

In the same way that poetry has changed greatly since Ancient Greece, elegies, too, have evolved since their Classical days. Let’s look at the form then, both historical and present, with contemporary elegy poem examples and tips for crafting new work.

But first, what is an elegy poem?

What is an Elegy Poem: Contents

What is an Elegy Poem?

The definition of an elegy poem has changed through history. Nowadays, elegy poetry is defined by a rumination or lamentation on loss, death, grief, or any other serious topic.

Nowadays, elegy poetry is defined by a rumination or lamentation on loss, death, grief, or any other serious topic.

If that strikes you as being a bit broadly defined, you’re not wrong. There’s debate within the realm of literary scholars as to what the term “elegy poem” properly refers to: are they poems on any serious topic, or only poems for the dead?

The Academy of American Poets defines the elegy as a poem strictly responding to the loss of a person or group. They note that the form is typically written in three stages of grief: lament, praise, and consolation or solace. Thus, elegies are not merely about the dead, but about consoling the reader about the subject’s death.

Conversely, contemporary elegies seem to eschew the consolatory aspect of the form’s history. Adele Bardazzi notes in “Maybe nothing is an elegy” that, since grief is both a collective force and a singular expression of one’s own deepest feeling, contemporary elegies resist genre categorization, electing instead to express the poet’s own unique grieving.

In other words, contemporary poems, by way of their resistance to easy categorization, have fractured how we might define elegiac poetry. So, instead of defining elegies by their preoccupation with death, it is better to define them as such:

Elegy poems are poems that explore the complexities of human grief.

The subject of that grief, and how the poet deals with it, are less important than the poem’s own contending with grief’s movements, textures, and singularity to the poet’s own emotional landscape.

Elegy poems are poems that explore the complexities of human grief.

A Brief History of Elegy Poems

Elegy in the Ancient World

Elegies are first recorded as involving death or grief, but what defined an elegy in antiquity was not its subject matter. The poems labeled as such in Ancient Greece were called elegies because they utilized one key defining feature: elegiac couplets.

Elegiac couplets follow this rhythm and meter: one line of dactylic hexameter, followed by one line of dactylic pentameter.

To break this down: a dactyl is a foot of poetry in which one stressed syllable is followed by two unstressed syllables. An English-language word that follows this is “freshener.”

A hexameter means there are 6 dactyls; a pentameter means there are 5. So Each couplet is composed of 11 dactyls: 6 in the first line, 5 in the next.

“Elegy” itself comes from the Greek, meaning “woe, cry.” Initially, they were funeral songs written in that elegiac verse. Around the 7th century BC, those elegiac couplets were then used to explore other themes, typically serious in nature, or else with strong emotional resonance: war, heartbreak, the meaning of life, etc.

Elegy in Europe

Like so much of European culture, the Romans eventually co-opted the form from Ancient Greece; then the Roman Empire ended, the form was lost, the form found resurgence in the Renaissance, and the rest, pun intended, is history.

As such, you may be familiar with one of the more famous elegy poem examples, written in the late-Neoclassical period: “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” by Thomas Gray. By this point, elegies were not written in elegiac verse—this one, as is common for the day, was written in iambic pentameter. Here are the first three quatrains:

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd wind slowly o’er the lea,

The plowman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

Now fades the glimm’ring landscape on the sight,

And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds;

Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tow’r

The moping owl does to the moon complain

Of such, as wand’ring near her secret bow’r,

Molest her ancient solitary reign.

Elegy Vs Eulogy

Elegies and eulogies are sometimes mistaken, due to their similarity in both spelling and setting.

A eulogy (Greek: “good word”) is a speech or passage of prose that honors someone recently deceased. You will hear these at funerals and, occasionally, read them as part of an obituary.

Elegies are poems on serious topics, including, but not limited to, death. While perhaps an elegy might be written as part of a eulogy (meaning: it is read at that person’s funeral), the two are different both in terms of form and intent.

The 3-Part Structure of Traditional Elegy Poems

Traditionally, elegies followed a three-part structure, in which the poet explored:

- Lament: The poet’s expression of sadness, sorrow, grief, or pain, typically regarding the recent death of a person.

- Praise: The poet’s admiration of the deceased, including the life they lived, their legacy, and/or their overall character.

- Consolation: The poet’s invocation of solace—that the deceased lives on in another world, that their impact will reverberate throughout this world, etc.

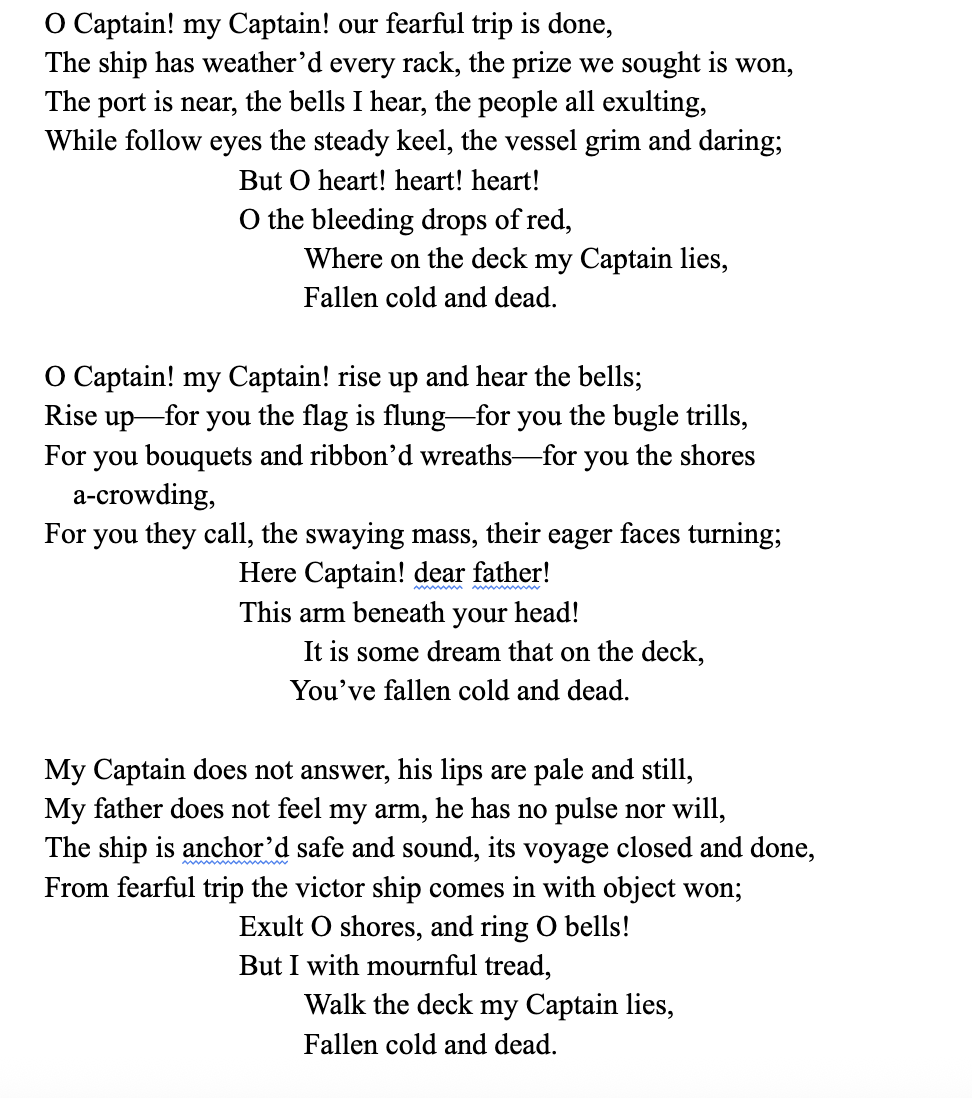

You can kind of see this structure at play in Walt Whitman’s famous poem “O Captain! My Captain!” The poem’s moment of consolation is perhaps halfhearted, but still the poem reaches catharsis through this classic elegy structure, partitioned into three corresponding stanzas.

Contemporary Elegy Poem Examples

Contemporary elegy poems do not require elegiac couplets, nor do they have to follow a three-part structure. Contemporary poets are challenging both the subject and form of elegiac poetry, wielding poetry’s formal qualities to explore the singular intensities of grief and loss.

Here are a few good contemporary elegy poem examples from living poets.

“OBIT” by Victoria Chang

My Mother’s Teeth—died twice, once in 1965, all pulled out from gum disease. Once again on August 3, 2015. The fake teeth sit in a box in the garage. When she died, I touched them, smelled them, thought I heard a whimper. I shoved the teeth into my mouth. But having two sets of teeth only made me hungrier. When my mother died, I saw myself in the mirror, her words in a ring around my mouth, like powder from a donut. Her last words were in English. She asked for a Sprite. I wonder whether her last thought was in Chinese. I wonder what her last thought was. I used to think that a dead person’s words die with them. Now I know that they scatter, looking for meaning to attach to like a scent. My mother used to collect orange blossoms in a small shallow bowl. I pass the tree each spring. I always knew that grief was something I could smell. But I didn’t know that it’s not actually a noun but a verb. That it moves.

This prose poem excavates the weirdness of grief: its textures and imagery, its uncanny revelations.

Much of the poem’s power comes from what it doesn’t state. For example, the second death of the mother’s teeth implies, but doesn’t state, that it’s the mother herself who has died. Somehow, looking at death through the periphery like this makes it even more gutting.

This poem comes out of Chang’s collection OBIT, which is certainly a collection of elegies, but is also a rumination on the role language plays in elegy. Chang observes that grief is a verb, and revelations like this are scattered throughout the work. You can find another example of Chang’s elegy poems at this poetry prompt on accidents of language.

“Elegy” by Aracelis Girmay

What to do with this knowledge

that our living is not guaranteed?

Perhaps one day you touch the touch the young branch

of something beautiful. & it grows & grows

despite your birthdays & the death certificate,

& it one day shades the heads of something beautiful

or makes itself useful to the nest. Walk out

of your house, then, believing in this.

Nothing else matters.

All above us is the touching

of strangers & parrots,

some of them human,

some of them not human.

Listen to me. I am telling you

a true thing. This is the only kingdom.

The kingdom of touching;

the touches of the disappearing, things.

This poem comes from Girmay’s collection Kingdom Animalia. I love this take on the elegy, because it mourns future loss, or perhaps is an elegy of mortality itself: the duality of our impermanence and the permanent effect we may leave on the world.

There’s certainly a mystery to this work. Why, specifically, “strangers & parrots”? What do parrots have to do with this piece, other than that they might live in those shady trees? I experience this poem as a sort of mystic insight, drawing upon a world not quite seen, to grasp that this world is “the kingdom of touching”—that we all, in some way, leave our eternal mark.

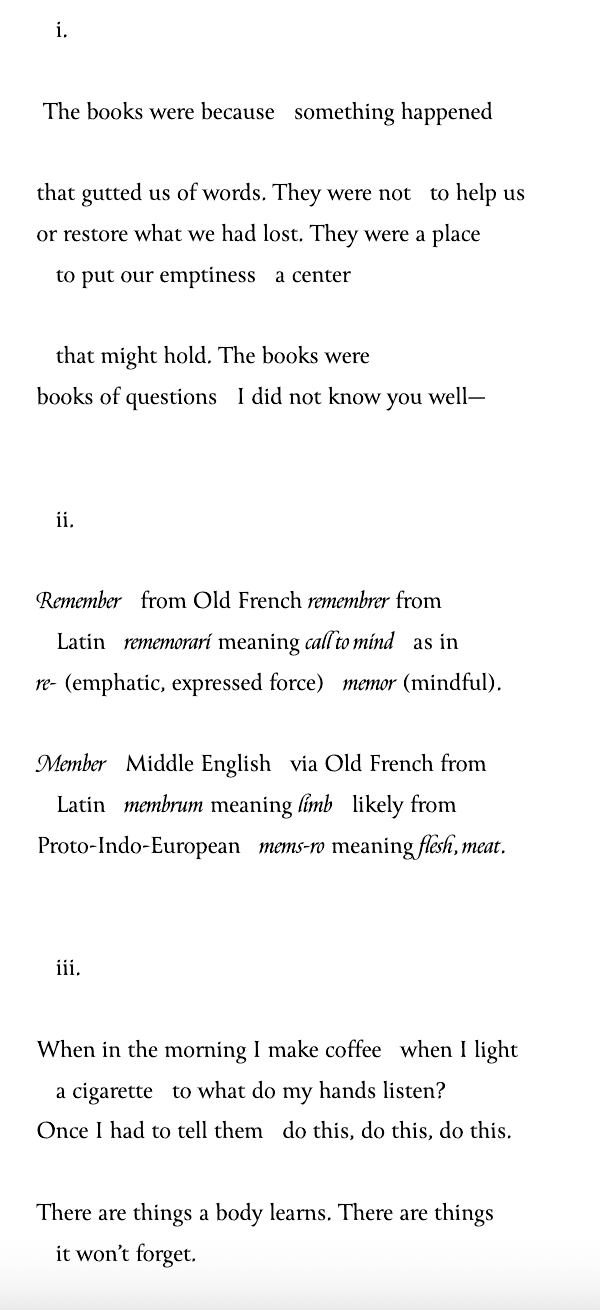

“Notes Toward an Elegy, or What the Books Were For” by Hannah Aizenman

Retrieved from the Internet Archive, originally published at BOAAT.

This approach to an elegy poem is interesting, in that the subject of elegy is peripheral; the speaker writes a poem collecting material towards that elegy, but not the elegy itself.

This is certainly a modern take on the genre, but no less interesting. What does it mean when the topic of lament occurs at the edges? When the reader doesn’t know what the topic is, but still feels its presence haunting the language? I can’t say—I only know that, when a source of grief cannot be looked at directly, what emerges from the peripheries is no less gutting.

“Elegy for a Walnut Tree” by W.S. Merwin

Old friend now there is no one alive

who remembers when you were young

it was high summer when I first saw you

in the blaze of day most of my life ago

with the dry grass whispering in your shade

and already you had lived through wars

and echoes of wars around your silence

through days of parting and seasons of absence

with the house emptying as the years went their way

until it was home to bats and swallows

and still when spring climbed toward summer

you opened once more the curled sleeping fingers

of newborn leaves as though nothing had happened

you and the seasons spoke the same language

and all these years I have looked through your limbs

to the river below and the roofs and the night

and you were the way I saw the world

In some ways, this piece is in lineage with the pastoral elegy poem. Pastoral elegies are poems that lament the loss of the pastoral or rural lifestyle. They can be found throughout the Renaissance and beyond in the English-speaking world, and like both pastorals and elegies, pastoral elegies have their own set of traditional requirements.

Merwin here isn’t invoking those same requirements, but there’s still a sense of loss reflected in a natural landscape. That loss is more a loss of innocence than anything else: Merwin’s speaker reflects on his own life through the tree’s, and the elegy really is for the time that has passed itself.

How to Write an Elegy Poem

Poetry’s capacity for nuance, complexity, and multiplicity often makes it best suited to tackle the strangeness of grief. Although these experiences often evade easy language, and grief feels singular to the individual, the craft of successful poetry writing can help you put words to these odd emotions.

As such, here are some tips on how to write an elegy poem.

Stare Peripherally At Your Grief

You might find yourself staring directly at the source of your grieving, but lacking the language to write about it. How do you enter into a poem whose topic is the totality of your loss?

Sometimes, the topic of your lament is better explored at the margins and peripheries. You can see that in the latter two elegy poem examples we shared: Aizenman’s poem anticipates the need for an elegy before its unnamed subject happens; Merwin’s walnut tree is a doorway into exploring his own life.

To put it a different way, the poem’s initiating subject is different than its generated subject, a topic we explain here.

Try to enter into lamentation through backdoors and hidden alleyways. What images, ideas, and senses are evoked in relation to the topic of your grief? How can you synthesize those items into a portrait of your loss?

Root Lamentation in Concrete Imagery

A poem does not need to be entirely concrete and imagistic. But it’s important that the emotions and experiences explored in your poem are demonstrated concretely.

Because the topic of an elegy poem is loss, grief, or lamentation, you likely don’t need to tell the reader “I’m sad” or “this experience is painful.” (Certainly, you can use those phrases in a first draft, but reconsider them in revision.) Readers probably won’t feel the poem’s pain just by having it named; it takes the craft tools of poetry, imagery included, to transmit an embodied experience of that pain.

This goes for any emotion in poetry—positive, negative, or neutral. Chang’s poem “OBIT” is a great example—Chang does name grief as such, but also demonstrates that grief in the poem’s symbolism, word choice, and interior exploration.

You Can Employ Topics of Elegy, Like Death, Metaphorically

Because of the elegy poem’s history and heightened sense of loss, it’s a topic perfectly suited for death. But, don’t feel like your poem has to be about something large, existential, or easily identified: poetry makes space for both the sublime and miniscule.

The topics of elegy can be employed metaphorically. What I mean is, you don’t need to write about the death of someone you love. It could be the death of something intangible: an elegy for third places, perhaps, or the era before internet and cellular.

Girmay does something like this in her “Elegy.” The poem’s lamentation is of our own ephemerality: that our selves, our touch, disappears (yet still changes the world forever). This is not an elegy in the traditional sense: the loss is anticipated, zoomed out, and somewhat abstracted. Death becomes both real and metaphorical, oriented towards something metaphysical.

Consider Form and Lineage

Poetry’s formal qualities allow a poem its complexity. Poetry often has to push language to say new things—a fact that is particularly useful in the face of grief, which so often evades and challenges language itself.

As such, give some thought to what form can accomplish for your poem, either in a first draft or as you revise. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Aizenman’s piece is in 3 sections, even if it doesn’t follow the traditional 3-part structure of classical elegy poems.

A different example that I love to teach comes from our instructor Ollie Schminkey. Check out their poem “My Father”, which wields the contrapuntal form to great effect.

You can also read different elegy poems and write a poem in lineage with it. “After” poems are a great way to take inspiration and turn it into your own successful poems.

Learn more about poetry forms here:

https://writers.com/what-is-form-in-poetry

Write Towards Insight or Epiphany

Poetry, and writing in general, offer solace by organizing our experiences into language and helping us better understand them. As such, you will find your elegy accomplishes what it wants to if you don’t just explore the contours of your sadness, but find the meaning of it—the surprise wisdom that suddenly happens from writing.

There’s no rulebook for finding epiphany. But if you reread the elegy poem examples we shared, you’ll find epiphany in all of them: discoveries that could only have occurred through the process of the poem itself.

The advice here, then, is to allow yourself to name what you don’t know, to write into complexity, and to write from a place of negative capability—inviting mystery into your work and the insight that comes from it.

Further Resources on Writing Poetry

If you’re interested in honing the craft of successful poetry writing, here are some resources to further your exploration:

- What is Poetry?

- Finding Poetry Inspiration

- How to Start a Poem

- How to Write a Poem

- How to Write a Free Verse Poem

- Line Breaks in Poetry

Write Elegy Poems at Writers.com

The classes at Writers.com will help you explore the topic of your elegy and refine it into successful poetry. Take a look at our upcoming online poetry writing courses and find the course that’s right for you.

Thank you, Sean, for your straightforward, thoughtful piece on writing elegies. I intend to rewrite a poem I was going to read at a gathering celebrating my friend’s life.