The short story is a fiction writer’s laboratory: here is where you can experiment with characters, plots, and ideas without the heavy lifting of writing a novel. Learning how to write a short story is essential to mastering the art of storytelling. With far fewer words to worry about, storytellers can make many more mistakes—and strokes of genius!—through experimentation and the fun of fiction writing.

Nonetheless, the art of writing short stories is not easy to master. How do you tell a complete story in so few words? What does a story need to have in order to be successful? Whether you’re struggling with how to write a short story outline, or how to fully develop a character in so few words, this guide is your starting point.

Famous authors like Virginia Woolf, Haruki Murakami, and Agatha Christie have used the short story form to play with ideas before turning those stories into novels. Whether you want to master the elements of fiction, experiment with novel ideas, or simply have fun with storytelling, here’s everything you need on how to write a short story step by step.

How to Write a Short Story: Contents

- The Core Elements of a Short Story

- How to Write a Short Story Outline

- How to Write a Short Story Step by Step

- How to Write a Short Story: The Short Story Checklist

- How to Write a Short Story: Length and Setting

- How to Write a Short Story: Point of View

- How to Write a Short Story: Protagonist, Antagonist, Motivation

- How to Write a Short Story: Characters

- How to Write a Short Story: Prose

- How to Write a Short Story: Story Structure

- How to Write a Short Story: Capturing Reader Interest

- Where to Read and Submit Short Stories

The Core Elements of a Short Story

There’s no secret formula to writing a short story. However, a good short story will have most or all of the following elements:

- A protagonist with a certain desire or need. It is essential for the protagonist to want something they don’t have, otherwise they will not drive the story forward.

- A clear dilemma. We don’t need much backstory to see how the dilemma started; we’re primarily concerned with how the protagonist resolves it.

- A decision. What does the protagonist do to resolve their dilemma?

- A climax. In Freytag’s Pyramid, the climax of a story is when the tension reaches its peak, and the reader discovers the outcome of the protagonist’s decision(s).

- An outcome. How does the climax change the protagonist? Are they a different person? Do they have a different philosophy or outlook on life?

Of course, short stories also utilize the elements of fiction, such as a setting, plot, and point of view. It helps to study these elements and to understand their intricacies. But, when it comes to laying down the skeleton of a short story, the above elements are what you need to get started.

Note: a short story rarely, if ever, has subplots. The focus should be entirely on a single, central storyline. Subplots will either pull focus away from the main story, or else push the story into the territory of novellas and novels.

The shorter the story is, the fewer of these elements are essentials. If you’re interested in writing short-short stories, check out our guide on how to write flash fiction.

Article continues below…

Short Story Writing Courses We Think You'll Love

We've hand-picked these courses to help you flourish as a writer.

Writing the Short Story

Create new work with fresh language, universal themes, sustained mystery and memorable characters. Stimulate your imagination.

Find Out More

Flash Fiction: Writing the Short-Short Story

Write 1–3-page flash fiction in this online course with Barbara Henning, drawing on classic, poetic & experimental elements. Read the...

Find Out MoreOr click below to view all courses.

See CoursesArticle continues…

How to Write a Short Story Outline

Some writers are “pantsers”—they “write by the seat of their pants,” making things up on the go with little more than an idea for a story. Other writers are “plotters,” meaning they decide the story’s structure in advance of writing it.

You don’t need a short story outline to write a good short story. But, if you’d like to give yourself some scaffolding before putting words on the page, this article answers the question of how to write a short story outline:

https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-story-outline

How to Write a Short Story Step by Step

There are many ways to approach the short story craft, but this method is tried-and-tested for writers of all levels. Here’s how to write a short story step-by-step.

1. Start With an Idea

Often, generating an idea is the hardest part. You want to write, but what will you write about?

What’s more, it’s easy to start coming up with ideas and then dismissing them. You want to tell an authentic, original story, but everything you come up with has already been written, it seems.

Here are a few tips:

- Originality presents itself in your storytelling, not in your ideas. For example, the premise of both Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Ostrovsky’s The Snow Maiden are very similar: two men and two women, in intertwining love triangles, sort out their feelings for each other amidst mischievous forest spirits, love potions, and friendship drama. The way each story is written makes them very distinct from one another, to the point where, unless it’s pointed out to you, you might not even notice the similarities.

- An idea is not a final draft. You will find that exploring the possibilities of your story will generate something far different than the idea you started out with. This is a good thing—it means you made the story your own!

- Experiment with genres and tropes. Even if you want to write literary fiction, pay attention to the narrative structures that drive genre stories, and practice your storytelling using those structures. Again, you will naturally make the story your own simply by playing with ideas.

If you’re struggling simply to find ideas, try out this prompt generator, or pull prompts from this Twitter.

2. Outline, OR Conceive Your Characters

If you plan to outline, do so once you’ve generated an idea. You can learn about how to write a short story outline earlier in this article.

If you don’t plan to outline, you should at least start with a character or characters. Certainly, you need a protagonist, but you should also think about any characters that aid or inhibit your protagonist’s journey.

When thinking about character development, ask the following questions:

- What is my character’s background? Where do they come from, how did they get here, where do they want to be?

- What does your character desire the most? This can be both material or conceptual, like “fitting in” or “being loved.”

- What is your character’s fatal flaw? In other words, what limitation prevents the protagonist from achieving their desire? Often, this flaw is a blind spot that directly counters their desire. For example, self hatred stands in the way of a protagonist searching for love.

- How does your character think and speak? Think of examples, both fictional and in the real world, who might resemble your character.

In short stories, there are rarely more characters than a protagonist, an antagonist (if relevant), and a small group of supporting characters. The more characters you include, the longer your story will be. Focus on making only one or two characters complex: it is absolutely okay to have the rest of the cast be flat characters that move the story along.

Learn more about character development here:

https://writers.com/character-development-definition

3. Write Scenes Around Conflict

Once you have an outline or some characters, start building scenes around conflict. Every part of your story, including the opening sentence, should in some way relate to the protagonist’s conflict.

Conflict is the lifeblood of storytelling: without it, the reader doesn’t have a clear reason to keep reading. Loveable characters are not enough, as the story has to give the reader something to root for.

Take, for example, Edgar Allan Poe’s classic short story The Cask of Amontillado. We start at the conflict: the narrator has been slighted by Fortunato, and plans to exact revenge. Every scene in the story builds tension and follows the protagonist as he exacts this revenge.

In your story, start writing scenes around conflict, and make sure each paragraph and piece of dialogue relates, in some way, to your protagonist’s unmet desires.

Read more about writing effective conflict here:

4. Write Your First Draft

The scenes you build around conflict will eventually be stitched into a complete story. Make sure as the story progresses that each scene heightens the story’s tension, and that this tension remains unbroken until the climax resolves whether or not your protagonist meets their desires.

Don’t stress too hard on writing a perfect story. Rather, take Anne Lamott’s advice, and “write a shitty first draft.” The goal is not to pen a complete story at first draft; rather, it’s to set ideas down on paper. You are simply, as Shannon Hale suggests, “shoveling sand into a box so that later [you] can build castles.”

5. Step Away, Breathe, Revise

Whenever Stephen King finishes a novel, he puts it in a drawer and doesn’t think about it for 6 weeks. With short stories, you probably don’t need to take as long of a break. But, the idea itself is true: when you’ve finished your first draft, set it aside for a while. Let yourself come back to the story with fresh eyes, so that you can confidently revise, revise, revise.

In revision, you want to make sure each word has an essential place in the story, that each scene ramps up tension, and that each character is clearly defined. The culmination of these elements allows a story to explore complex themes and ideas, giving the reader something to think about after the story has ended.

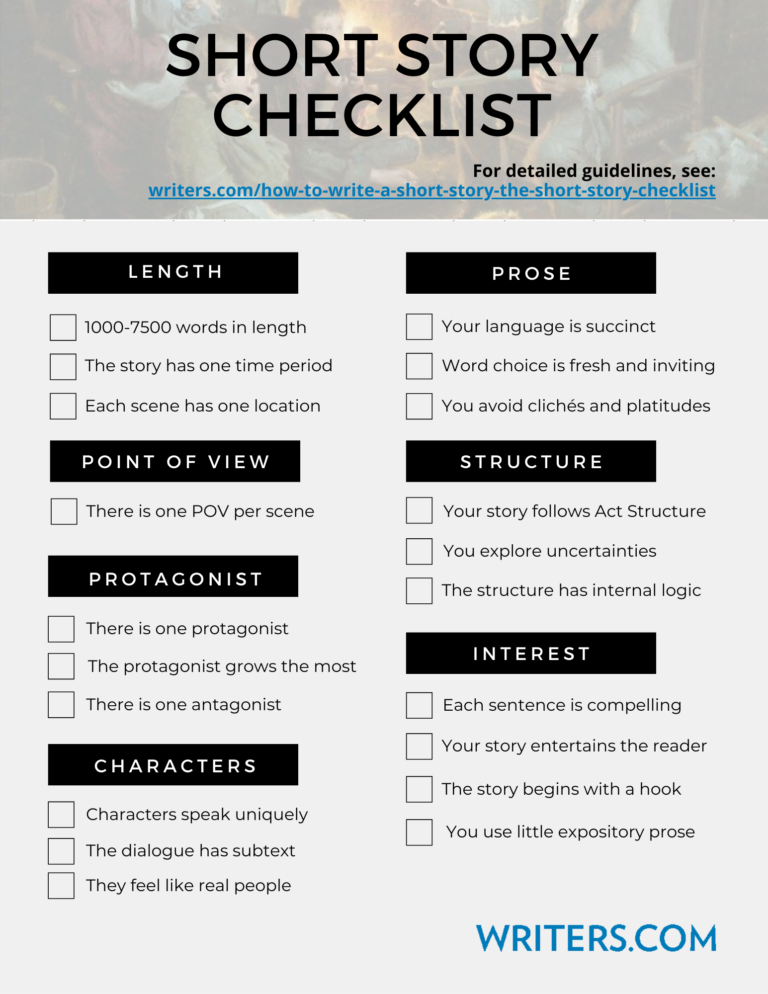

6. Compare Against Our Short Story Checklist

Does your story have everything it needs to succeed? Compare it against this short story checklist, as written by our instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko.

How to Write a Short Story: The Short Story Checklist

Below is a collection of practical short story writing tips by Writers.com instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko. Each paragraph is its own checklist item: a core element of short story writing advice to follow unless you have clear reasons to the contrary. We hope it’s a helpful resource in your own writing.

Update 9/1/2020: We’ve now made a summary of Rosemary’s short story checklist available as a PDF download. Enjoy!

How to Write a Short Story: Length and Setting

Your short story is 1000 to 7500 words in length.

The story takes place in one time period, not spread out or with gaps other than to drive someplace, sleep, etc. If there are those gaps, there is a space between the paragraphs, the new paragraph beginning flush left, to indicate a new scene.

Each scene takes place in one location, or in continual transit, such as driving a truck or flying in a plane.

How to Write a Short Story: Point of View

Unless it’s a very lengthy Romance story, in which there may be two Point of View (POV) characters, there is one POV character. If we are told what any character secretly thinks, it will only be the POV character. The degree to which we are privy to the unexpressed thoughts, memories and hopes of the POV character remains consistent throughout the story.

You avoid head-hopping by only having one POV character per scene, even in a Romance. You avoid straying into even brief moments of telling us what other characters think other than the POV character. You use words like “apparently,” “obviously,” or “supposedly” to suggest how non-POV-characters think rather than stating it.

How to Write a Short Story: Protagonist, Antagonist, Motivation

Your short story has one clear protagonist who is usually the character changing most.

Your story has a clear antagonist, who generally makes the protagonist change by thwarting his goals.

(Possible exception to the two short story writing tips above: In some types of Mystery and Action stories, particularly in a series, etc., the protagonist doesn’t necessarily grow personally, but instead his change relates to understanding the antagonist enough to arrest or kill him.)

The protagonist changes with an Arc arising out of how he is stuck in his Flaw at the beginning of the story, which makes the reader bond with him as a human, and feel the pain of his problems he causes himself. (Or if it’s the non-personal growth type plot: he’s presented at the beginning of the story with a high-stakes problem that requires him to prevent or punish a crime.)

The protagonist usually is shown to Want something, because that’s what people normally do, defining their personalities and behavior patterns, pushing them onward from day to day. This may be obvious from the beginning of the story, though it may not become heightened until the Inciting Incident, which happens near the beginning of Act 1. The Want is usually something the reader sort of wants the character to succeed in, while at the same time, knows the Want is not in his authentic best interests. This mixed feeling in the reader creates tension.

The protagonist is usually shown to Need something valid and beneficial, but at first, he doesn’t recognize it, admit it, honor it, integrate it with his Want, or let the Want go so he can achieve the Need instead. Ideally, the Want and Need can be combined in a satisfying way toward the end for the sake of continuity of forward momentum of victoriously achieving the goals set out from the beginning. It’s the encounters with the antagonist that forcibly teach the protagonist to prioritize his Needs correctly and overcome his Flaw so he can defeat the obstacles put in his path.

The protagonist in a personal growth plot needs to change his Flaw/Want but like most people, doesn’t automatically do that when faced with the problem. He tries the easy way, which doesn’t work. Only when the Crisis takes him to a low point does he boldly change enough to become victorious over himself and the external situation. What he learns becomes the Theme.

Each scene shows its main character’s goal at its beginning, which aligns in a significant way with the protagonist’s overall goal for the story. The scene has a “charge,” showing either progress toward the goal or regression away from the goal by the ending. Most scenes end with a negative charge, because a story is about not obtaining one’s goals easily, until the end, in which the scene/s end with a positive charge.

The protagonist’s goal of the story becomes triggered until the Inciting Incident near the beginning, when something happens to shake up his life. This is the only major thing in the story that is allowed to be a random event that occurs to him.

How to Write a Short Story: Characters

Your characters speak differently from one another, and their dialogue suggests subtext, what they are really thinking but not saying: subtle passive-aggressive jibes, their underlying emotions, etc.

Your characters are not illustrative of ideas and beliefs you are pushing for, but come across as real people.

How to Write a Short Story: Prose

Your language is succinct, fresh and exciting, specific, colorful, avoiding clichés and platitudes. Sentence structures vary. In Genre stories, the language is simple, the symbolism is direct, and words are well-known, and sentences are relatively short. In Literary stories, you are freer to use more sophisticated ideas, words, sentence structures, styles, and underlying metaphors and implied motifs.

How to Write a Short Story: Story Structure

Your plot elements occur in the proper places according to classical Three Act Structure (or Freytag’s Pyramid) so the reader feels he has vicariously gone through a harrowing trial with the protagonist and won, raising his sense of hope and possibility. Literary short stories may be more subtle, with lower stakes, experimenting beyond classical structures like the Hero’s Journey. They can be more like vignettes sometimes, or even slice-of-life, though these types are hard to place in publications.

In Genre stories, all the questions are answered, threads are tied up, problems are solved, though the results of carnage may be spread over the landscape. In Literary short stories, you are free to explore uncertainty, ambiguity, and inchoate, realistic endings that suggest multiple interpretations, and unresolved issues.

Some Literary stories may be nonrealistic, such as with Surrealism, Absurdism, New Wave Fabulism, Weird and Magical Realism. If this is what you write, they still need their own internal logic and they should not be bewildering as to the what the reader is meant to experience, whether it’s a nuanced, unnameable mood or a trip into the subconscious.

Literary stories may also go beyond any label other than Experimental. For example, a story could be a list of To Do items on a paper held by a magnet to a refrigerator for the housemate to read. The person writing the list may grow more passive-aggressive and manipulative as the list grows, and we learn about the relationship between the housemates through the implied threats and cajoling.

How to Write a Short Story: Capturing Reader Interest

Your short story is suspenseful, meaning readers hope the protagonist will achieve his best goal, his Need, by the Climax battle against the antagonist.

Your story entertains. This is especially necessary for Genre short stories.

The story captivates readers at the very beginning with a Hook, which can be a puzzling mystery to solve, an amazing character’s or narrator’s Voice, an astounding location, humor, a startling image, or a world the reader wants to become immersed in.

Expository prose (telling, like an essay) takes up very, very little space in your short story, and it does not appear near the beginning. The story is in Narrative format instead, in which one action follows the next. You’ve removed every unnecessary instance of Expository prose and replaced it with showing Narrative. Distancing words like “used to,” “he would often,” “over the years, he,” “each morning, he” indicate that you are reporting on a lengthy time period, summing it up, rather than sticking to Narrative format, in which immediacy makes the story engaging.

You’ve earned the right to include Expository Backstory by making the reader yearn for knowing what happened in the past to solve a mystery. This can’t possibly happen at the beginning, obviously. Expository Backstory does not take place in the first pages of your story.

Your reader cares what happens and there are high stakes (especially important in Genre stories). Your reader worries until the end, when the protagonist survives, succeeds in his quest to help the community, gets the girl, solves or prevents the crime, achieves new scientific developments, takes over rule of his realm, etc.

Every sentence is compelling enough to urge the reader to read the next one—because he really, really wants to—instead of doing something else he could be doing. Your story is not going to be assigned to people to analyze in school like the ones you studied, so you have found a way from the beginning to intrigue strangers to want to spend their time with your words.

Where to Read and Submit Short Stories

Whether you’re looking for inspiration or want to publish your own stories, you’ll find great literary journals for writers of all backgrounds at this article:

https://writers.com/short-story-submissions

Learn How to Write a Short Story at Writers.com

The short story takes an hour to learn and a lifetime to master. Learn how to write a short story with Writers.com. Our upcoming fiction courses will give you the ropes to tell authentic, original short stories that captivate and entrance your readers.

Rosemary – Is there any chance you could add a little something to your checklist? I’d love to know the best places to submit our short stories for publication. Thanks so much.

Hi, Kim Hanson,

Some good places to find publications specific to your story are NewPages, Poets and Writers, Duotrope, and The Submission Grinder.

“ In Genre stories, all the questions are answered, threads are tied up, problems are solved, though the results of carnage may be spread over the landscape.”

Not just no but NO.

See for example the work of MacArthur Fellow Kelly Link.

[…] How to Write a Short Story: The Short Story Checklist […]

Thank you for these directions and tips. It’s very encouraging to someone like me, just NOW taking up writing.

[…] Writers.com. A great intro to writing. https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-short-story […]

Hello:

I started to write seriously in the late 70’s. I loved to write in High School in the early 60’s but life got in the way. Around the 00’s many of the obstacles disappeared. Since then I have been writing more, and some of my work was vanilla transgender stories. Here in 2024 transgender stories have become tiresome because I really don’t have much in common with that mind set.

The glare of an editor that could potentially pay me is quite daunting, so I would like to start out unpaid to see where that goes. I am not sure if a writer’s agent would be a good fit for me. My work life was in the Trades, not as some sort of Academic. That alone causes timidity, but I did read about a fiction writer who had been a house painter.

This is my first effort to publish since the late 70’s. My pseudonym would perhaps include Ahabidah.

Gwen Boucher.