The world of fiction writing can be split into two categories: literary fiction vs. genre fiction. Literary fiction (lit fic) generally describes work that’s character-driven and realistic, whereas genre fiction generally describes work that’s plot-driven and based on specific tropes.

That said, these kinds of reductive definitions are unfair to both genres. Literary fiction can absolutely be unrealistic, trope-y, and plot-heavy, and genre fiction can certainly include well-developed characters in real-world settings.

Part of the issue with these definitions is that literary fiction vs. genre fiction describes a binary. Sure, every piece of fiction can be categorized in one of two ways, but there’s a wide variety of fiction out there, and very little of it falls neatly in a particular box. If our human experiences are widely variegated, our fiction should be, too.

So, let’s break down this binary a bit further. What are the elements of literary fiction vs. genre fiction, how can we better define these categories, and what elements can you apply in your own fiction writing?

Along the way, we’ll take a look at some literary fiction examples, the different types of fiction genres, and some writing tips for each group. But first, let’s dissect the differences between literary fiction vs. genre fiction. (They’re not as different as you might think!)

Literary Fiction vs. Genre Fiction: Contents

Literary Fiction vs. Genre Fiction

Before we describe these two categories, it’s important to note their origins. The distinction between literary fiction vs. genre fiction is recent: book publishers had no need to make these categories until the 20th century, when genre labels became a marketing tool for mass publication.

For example, many consider Edgar Allan Poe to be the first modern mystery writer, as his 1841 story “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” was one of the first detective stories. But when he published this story, it was just that—a story. Terms like “mystery,” “thriller,” or “detective” wouldn’t start describing literature until the 1900s, particularly when these genre tags helped distinguish and market new works.

Nonetheless, literary fiction and genre fiction help describe today’s literary landscape. So, what do they mean?

Literary Fiction Definition

In general, literary fiction describes work that aims to resemble real life. (Of course, genre fiction can do this too, but we’ll get there in a moment.)

Literary fiction aims to resemble real life.

In order to transcribe real life, lit fic authors rely on the use of realistic characters, real-life settings, and complex themes, as well as the use of literary devices and experimental writing techniques.

Now, if you ask 100 different writers about what makes literary fiction “literary,” you could easily get 100 different answers. You might hear that, opposed to genre fiction, lit fic is:

- Character-driven (instead of plot driven).

- Complex and thematic.

- Based on real-life situations.

- Focused on life lessons and deeper meanings.

These distinctions are all well and good—except, genre fiction can be those things, too. Additionally, some examples of lit fic involve scenarios that would never happen in real life. For example, time travel and visions of the future occur in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, but the novel is distinctly literary in its focus on war.

Perhaps the best way to think about literary fiction is that it’s uncategorizable. Unlike genre fiction, which can be broken down even further into different types of fiction genres, lit fic doesn’t fall neatly into any of the genre boxes. Some literary fiction examples include To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, and A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens.

Unlike genre fiction, literary fiction can’t be subcategorized; it doesn’t break down further into genres.

Genre fiction, by contrast, provides us with neat categories that we can assign to different literary works. Let’s take a closer look at some of those categories.

Genre Fiction Definition

The primary feature of genre fiction is that it follows certain formulas and tropes. There are rules in genre fiction that don’t apply to literary fiction: tropes, structures, and archetypes that make for successful genre work.

There are rules in genre fiction that don’t apply to literary fiction: tropes, structures, and archetypes that make for successful genre work.

So, genre fiction is any piece of literature that follows a certain formula to advance the story. It’s important for genre writers to immerse themselves in the genre they’re writing, because even if they don’t want to follow a precise formula, they need to know how to break the rules. We’ll take a look at some of those conventions when we explore the types of fiction genres.

If literary fiction started borrowing from genre tropes, it would then become genre fiction. However, both categories can share similar themes and ideas, without being in the same camp.

Take, for example, the novel Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov. Lolita falls firmly in the category of lit fic, even though the novel centers around love, lust, and relationships.

If Lolita is about love, then why is it not considered a romance novel, which falls under genre fiction? Because Lolita doesn’t use any of the romance genre’s tropes. For starters, the novel is about a professor (Humbert Humbert) who falls in love with the adolescent Dolores, makes Dolores his step-daughter, and then molests her. Thankfully, you don’t see that often in romance novels.

More to the point, Lolita doesn’t use any of the romance genre’s conventions. There’s no exciting first encounter—no meet cute, no chance interaction, no love at first sight (though there is lust at first sight).

Neither does anything complicate the relationship between Humbert and Dolores—there’s no relationship to be had. The novel charts the power imbalance between a middle aged man and a girl who’s barely old enough to understand consent, much less old enough to enforce it. Romance genre conventions—like love triangles or meeting at the wrong time—simply don’t apply. Yes, many plot points do make it harder for Humbert to pursue Dolores, but those plot points aren’t conventions of the romance genre.

Literary Fiction vs. Genre Fiction: A Summary

To summarize, each category abides by the following definitions:

Literary Fiction: Fiction that cannot be categorized by any specific genre conventions, and which seeks to describe real-life reactions to complex events using well-developed characters, themes, literary devices, and experimentations in prose.

Genre Fiction: Fiction that follows specific genre conventions, using tropes, structures, plot points, and archetypes to tell a story.

Additionally, literary fiction may borrow from certain genre tropes, but never enough to fall into a specific genre camp. Genre fiction can also have complex characters, themes, and literary devices, and it can certainly reproduce real life situations, as long as it also follows genre conventions.

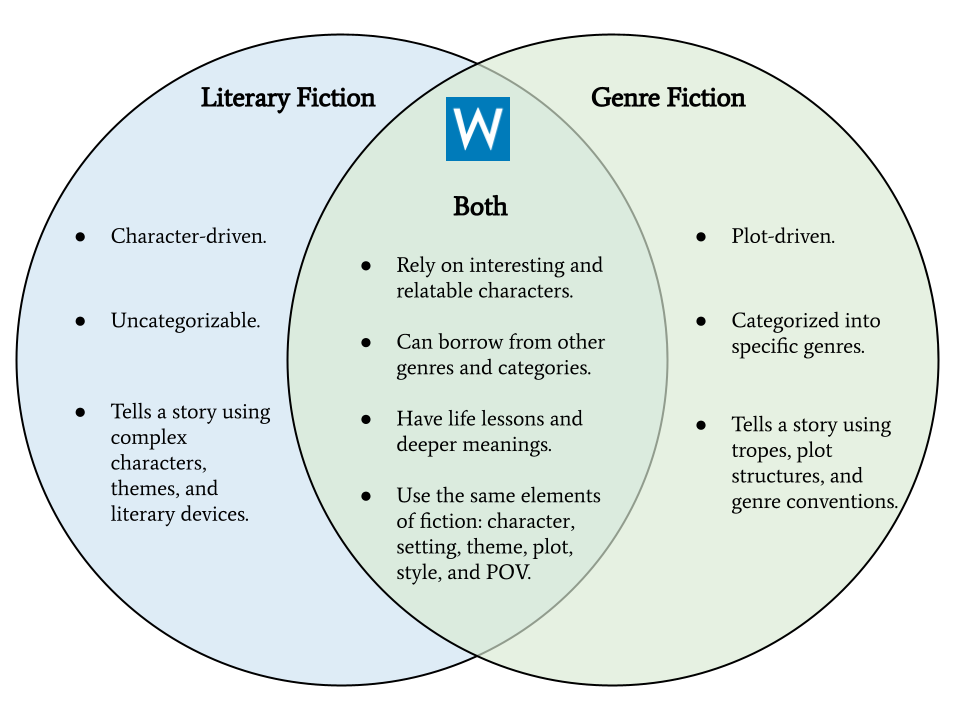

The differences between literary fiction vs. genre fiction have been mapped out below.

Literary Fiction vs. Genre Fiction Venn Diagram

More About Literary Fiction

Without the use of genre conventions, lit fic writers often struggle to tell a complete, compelling story. So, how do they do it?

Let’s take a look at some contemporary literary fiction books. We’ll briefly explore each example, taking a look at its themes and what makes the work “literary”.

Literary Fiction Books

All of the literary fiction examples below were published in the 21st century, to reflect the type of work that contemporary novelists write.

1. Pachinko by Min Jin Lee

Synopsis

Pachinko follows three generations of a Korean family that moves to Japan, during and after Japan’s occupation of Korea. The novel examines this family’s culture shock, their experiences with oppression and poverty, the enduring legacy of occupation.

Core Themes

The core theme of Pachinko is family: the value of family, the struggle to protect it, and the lengths one will go to make their family survive. These struggles are magnified in their juxtaposition to colonization, the other core theme of this novel. How did the Japanese occupation permanently affect the lives of Koreans?

What Makes This “Literary”?

Pachinko attempts to tell realistic stories, based on the lived experiences of many Korean families that endured Japan’s occupation. Additionally, the novel doesn’t follow a specific formula or set of plot points. Pachinko is organized in three parts, with each part focusing on the next generation of the same family, as well as their reaction to a different global event.

2. Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami

Synopsis

Kafka on the Shore follows two separate, yet metaphysically intertwined narratives. One story is about Kafka, a 15-year old boy who runs away from home after (unwittingly) murdering his father. In search of his lost mother and sister, Kafka ends up living in a library, where he meets the intelligent Oshima and begins his journey of healing.

The other narrative follows Nakata, an old man who became intellectually disabled in his youth following a mysterious accident. Nakata lost his ability to read and think abstractly, but he gained an ability to talk to cats. Nakata rescues a cat, and in doing so, begins his own path, which involves hitchhiking with a random truck driver and assassinating a cat killer.

On a metaphysical realm, Nakata’s actions are essential for Kafka to complete his own journey of spiritual healing. Though they never meet in person, their fates intertwine through spiritual means.

Core Themes

A recurring theme in Kafka on the Shore is the communicative power of music, which accompanies both Kafka and Nakata on their journeys. Additionally, questions of self-reliance, dreams versus reality, Shintoism, and the power of fate permeate the novel.

What Makes This “Literary”?

Murakami borrows from many different genres, including magical realism, absurdism, and fantasy. Yet the novel never leans too far into one genre. By combining these elements with his own brand of wit, mundanity, pop culture, spiritualism, and sexuality, Murakami creates an interconnected narrative about two equally unique protagonists. While Kafka on the Shore’s plot points are baffling and mysterious, it is the protagonists’ spiritual journeys which the novel focuses on.

3. Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Synopsis

Half of a Yellow Sun follows the lives of five individuals before, during, and after the Nigerian Civil War. The short-lived state of Biafra forces each character to make impossible decisions. A village boy is forcibly conscripted in the army; a university professor follows a dark path of alcoholism; the daughter of a war profiteer becomes the runner of a refugee camp, and her twin sister adopts her husband’s child, who was born out of wedlock. Finally, a British writer becomes obsessed with telling Biafra’s story, only to realize it isn’t his story to tell.

Core Themes

War, and everything about war, colors this novel’s thematic landscape. The novel dwells on the relationship between power and the people, especially since all of Biafra’s supporters—including its powerful supporters—are squashed under occupation. War also makes the novel’s characters contend with ideas of Socialism, Tribalism, Nationalism, Pan-Africanism, and Capitalism, among others. Other themes of this novel include family, power & corruption, and survival.

What Makes This “Literary”?

Although Half of a Yellow Sun centers around war, it’s not a “war story”. The novel is wholly unconcerned with war’s genre conventions, dwelling little on things like battle strategies or building suspense. Rather, the novel focuses on the human impact of war. The Nigerian Civil War displaces each main character, forcing them to confront awful truths and make heart-wrenching decisions as a result. Half of a Yellow Sun concerns itself with the consequences of war and political strife, especially given the ideal nature of the Biafran nation.

More About Genre Fiction

In many ways, genre fiction is no easier to summarize than literary fiction. Each genre has its own rules, tropes, character types, plot structures, and goals.

Mystery novels, for example, should present an uncrackable whodunnit that builds suspense and intrigue, whereas Romance novels should create tension between two characters who are meant for each other, but keep encountering setbacks in their relationship. Since each novel has different goals, they take drastically different paths to achieve those goals.

Below, we’ve summarized the rules, tropes, and goals for 8 popular fiction genres. Links and further readings are provided for writers who want to dive deeper into a specific type of genre fiction.

Types of Fiction Genres

Sci-Fi

Science Fiction, or Sci-Fi, explores fictional societies that are shaped by new and different technologies. Aliens might visit Earth, wars might take place across galaxies, humans might have bionic arms, or scientists might discover human immortality. The goal of most Sci-Fi is to explore man’s relationship to technology, as well as technology’s relationship to society, power, and reality.

Many of the technological innovations in Sci-Fi can double as themes. For example, the gene-editing technology in Margaret Atwood’s Oryx & Crake represents man’s hubris in trying to command nature, the result of which is a dystopian society that hastens its own apocalypse.

Prominent Science Fiction writers include Isaac Asimov, Philip K. Dick, Arthur C. Clarke, H. G. Wells, Margaret Atwood, Ted Chiang, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Octavia E. Butler. Here’s a list of common tropes in Science Fiction.

Thriller

Thriller novels attempt to tell engaging, suspenseful stories, often based on a complex protagonist undergoing a Hero’s Journey. A spy might chase down an international assassin, a boy might fake his own death, or a lawyer might have to prove she’s been framed for murder. In thriller novels, the protagonist faces a journey that’s long, dark, and arduous.

Thrillers often blend into other types of fiction genres. It’s common for a thriller to also be categorized as mystery, Sci-Fi, or horror, and even some romance thrillers exist. While the best thrillers have complicated protagonists, authors of thriller novels prioritize making each plot point juicy, compelling, and suspenseful.

Prominent thriller novelists include John Grisham, Stieg Larsson, Gillian Flynn, Dean Koontz, Megan Abbott, and Lisa Under. This article explains the key elements of thrillers.

Mystery

The mystery genre typically revolves around murder. (If not murder, then some other high-profile and complicated crime.) Usually told from the perspective of a detective or medical examiner, mystery novels present a host of clues, suspects, and possibilities—including red herrings and misleading info.

Because mystery revolves around crime, many novels delve deep into their characters’ psyches. A mystery novel might string you along with clues and plot points, but it’s the complicated characters and their unknown desires that make a mystery juicy.

Prominent mystery novelists include Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, Walter Mosley, Patricia Highsmith, Anthony Horowitz, and Louise Penny. Here are some considerations for writing mystery novels, and here are 5 mistakes to avoid when writing mystery.

Romance

Ah, l’amour. Romance novels follow the complicated relationships of lovers who, despite everything, are meant to be together. As they explore their relationship, each lover must embark on their own journey of growth and self-discovery.

The relationships in romance novels are never simple, but always satisfying. Lovers often meet under unique circumstances, they may be forbidden from loving each other, and they always mess things up a few times before they get it right. Alongside thriller, romance is often the bestselling genre, though it has its humble roots in the Gothic fiction of the 19th century.

Prominent romance novelists include Carolyn Brown, Nicholas Sparks, Catherine Bybee, Alyssa Cole, Beverly Jenkins, and Julia Quinn. Here’s a list of common tropes in the romance genre.

Fantasy

Fantasy novels require tons of worldbuilding and imagination. Wizards might go to battle, a man might chase after a unicorn, men and Gods might go to war with each other, or a hero might go on a mystical quest. What is impossible in real life is quotidian in fantasy.

Many works of fantasy borrow from mythology, folklore, and urban legend. Like Sci-Fi, many of the magical elements in fantasy novels can double as symbols or themes. The line between Sci-Fi and fantasy is often unclear: for example, an alien invasion is categorized as Sci-Fi, but the journey to defeat those aliens can easily resemble a fantasy novel.

Prominent fantasy novelists include J. R. R. Tolkien, George R. R. Martin, Andre Norton, Rick Riordan, C. S. Lewis, Zen Cho, and Erin Morgenstern. Here are some tropes in the fantasy genre, as well as our exploration of urban fantasy.

Magical Realism

Magical Realism blends the fantastical with the everyday. There won’t be grandwizards, alternate universes, or potions with unicorn tears, but there might be a man whose head is tied to his body, or a woman who cries tears of fabric.

In other words, fantasy slips into everyday life, but the characters don’t have magic at their disposal—they react as only mortals know how to react to magic. Because it is a relatively young genre, and because it often focuses on characters instead of plot points, magical realism is often seen as a more “literary” genre of genre fiction. Magical realism has its roots in the storytelling of Central and South American novelists.

Prominent authors of magical realism include Isabel Allende, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Carmen Maria Machado, Haruki Murakami, Samanta Schweblin, Jorge Louis Borges, and Salman Rushdie. Learn more about magical realism here.

Horror

Horror writers are masters of invoking fear in the reader. Through a combination of tone, atmosphere, plotting, the introduction of ambiguous (and unambiguous) threats, and the author’s own imagination, horror novels push their characters to the brink of survival.

Most horror novels involve supernatural elements, including monsters, ghosts, god-like figures, satanic rituals, or Sci-Fi creatures. Sometimes the protagonists are armed and ready, but usually, the protagonists are trapped and trying to escape some unfathomable danger.

Prominents horror writers include Stephen King, Edgar Allan Poe, Clive Barker, Bram Stoker, Mary Shelley, and Ray Bradbury. Here are some common tropes for horror writers.

Children’s

“You have to write the book that wants to be written. And if the book will be too difficult for grown-ups, then you write it for children.” —Madeleine L’Engle

Children’s fiction is technically its own category of fiction, but the genre does have its own tropes and conventions. With many similarities to the fable, children’s fiction teaches important life lessons through the journeys of memorable characters, who are often the same age as the novel’s intended reader.

Writing for children is much harder than commonly believed. Whether you’re writing a picture book or a YA novel, you have to balance your book’s core themes and ideas with the reading level of your audience—without “talking down to” the reader.

Prominent children’s writers include A. A. Milne, Roald Dahl, Dr. Seuss, Madeleine L’Engle, Diana Wynne Jones, Anne Fine, and Peggy Parish. Here are 10 tips for picture book writers, and here is advice for YA novelists.

Explore Literary Fiction vs. Genre Fiction at Writers.com

With so many works being published in both literary fiction and genre fiction, it helps to have people read your work before you submit it somewhere. That’s what Writers.com is here for. From our upcoming fiction courses to the Writers.com Community, we help writers of all stripes master the conventions of their genre.

Hi Sean,

Great example using Lolita for why the book doesn’t fall under the ‘romance’ category (due to the way it does not use romance tropes – indeed, it is almost an ‘anti-romance’). There’s a great line where Nabokov was asked about its inspirations and he said he read a story about a chimpanzee that was taught to paint and it’s great masterwork turned out to be a painting of the bars of its cage (perhaps he was implying that his protagonist similarly represents the limits of his own awareness, since he doesn’t seem able to empathize with or consider Lolita’s subjective experience).

I wasn’t sure about the definition of literary fiction (as being that which resembles real life), since so much literary fiction is surreal (e.g. Kafka) or upends realist modes (e.g. when an author uses second person to make the reader an active participant in the story, e.g. Italo Calvino in ‘If on a winter’s night a traveler’). So I’m curious about that definition.

Thank you for mentioning Now Novel, too.

Hi Jordan, thanks for your comment!

You make a good point, and I agree wholeheartedly. I’ve emended our definition to say that literary fiction describes “real-life reactions to complex events.” When magic and sci-fi are out of the question, what can people do in their limited power against terrible things–like, say, waking up as a bug?

As for Calvino’s experimentations with prose and POV, it’s hard to summarize that into any meaningful definition–he is, in several ways, his own category. That said, I think his ability to cast the reader as the protagonist helps build the type of empathy that lit fic is best suited for, and experimentations in prose are one of the many tools at the disposal of both literary and genre novelists.

Nabokov’s anecdote about the chimpanzee fascinates me–I haven’t heard that story, but it reveals so much about Nabokov’s psyche. His empathy for the chimpanzee in a cage is striking.

I loved Now Novel’s advice for writing YA! Thanks for sharing it, and thanks again for your comment!

I’m curious as to why Margaret Atwood is categorized as a Sci-Fi novelist. I consider Atwood’s work to be literature, not formulaic and plot driven. Romance novels have historically been easy to categorize–they are basically fluff pieces, good for escaping the everyday and losing oneself in something safe and predictable. But what is the modern romance fiction? Is it Danielle Steele, or Colleen Hoover? I’m struggling to understand the difference between the NY Times Bestseller list, and the NY Times Recommended books list. Two lists that to a casual reader could seem interchangeable, but that serious readers understand differently. Most bestsellers (particularly trade paperback editions) are not considered “literature,” but the novels that are recommended by the NY times, or that are nominated, and sometimes receive, awards such as the National Book Award or the Nobel Prize in Literature. Would you consider books like ones by Colleen Hoover or Lucy Score genre fiction, or literary fiction? Full disclosure: I have not read anything by either of those authors—the characters and plots feel super formulaic and the writing isn’t that good (in my opinion).

This feels like it will be a great resource for the explanations I do not get in class. I look forward to spending time on this site.

[…] are lots of stereotypes associated with writing commercial genre fiction versus writing literary fiction. But even the most […]

Thank you! While at the library (my “third place”) a few years ago, a fellow patron and I were discussing books to recommend. He wanted literature. The way he spoke, literature was ONLY great works of the past, not recent “books”. So thank you for clarifying the difference.

A green diver in your sea of knowledge.

[…] with what you want to read in fiction. For example, maybe you like reading stories that bend genres, and you want a story that combines mystery, romance, historical fiction, and science […]