Many novels, movies, and plays follow what is known as the “Three-Act Structure.” This plot structure offers the scaffolding that many writers use to tell successful stories.

Once you know what the three-act structure is, you’ll see it everywhere: in every book you read and show you watch, you’ll notice where the plot shifts, where the climax falls, and how the storyteller has cast their magic. But, don’t think this structure makes storytelling boring: it is precisely what makes so many stories successful.

Although there are plenty of ways to invert, subvert, and disregard the three-act structure, knowing how it works—and why—is important for any storyteller looking to hone their craft. Let’s deconstruct the three-act structure, then, with an eye towards how it makes some of the most successful stories so successful.

What is the Three-Act Structure?

Are you familiar with the beginning, the middle, and the end? If so, then you are already somewhat acquainted with the idea of the three-act structure.

The three-act structure defines a successful story as happening in three acts.

The three-act structure defines a successful story as happening in three acts. Certain essential events must happen in each act before the story moves onto the next, and each act is weighted similarly, standing on its own and working with the other acts to tell the full story.

Aristotle and the Three-Act Structure

One of the oldest written records that discuss story structure comes from Aristotle’s Poetics, in which he argues that all stories are linear arcs that follow a narrative triangle: a story’s beginning that sets off a rising action, the story’s climactic, deciding moment, and the falling action that moves towards resolution.

Aristotle: All stories are linear arcs that follow a narrative triangle: a story’s beginning that sets off a rising action, the story’s climactic, deciding moment, and the falling action that moves towards resolution.

Article continues below…

Fiction Writing Courses We Think You'll Love

We've hand-picked these courses to help you flourish as a writer.

Plot Your Novel

Over eight weeks, you'll develop a solid basis in the fictional elements—protagonist, setting, secondary characters, point of view, plot, and...

Find Out More

Plot Your Novel with the Three-Act Structure

The 3 act structure gives us the scaffolding we can hang our stories off of. Come away from this class...

Find Out More

Rapid Story Development: A Master Plan for Building Stories That Work

In this 10 week story writing class, Jeff Lyons pairs the Enneagram with story development techniques to revolutionize your writing...

Find Out MoreOr click below to view all courses.

See CoursesArticle continues…

Aristotle’s observations come from his vantage point in Western history. His writings occur during the 4th Century B.C.; at this point, the written Greek alphabet had only been around for about 400 or so years, prior to which all storytelling and literature had been oral in the Greek tradition. Writing, moreover, was a privileged endeavor, reserved for the educated and literate upper echelons of Greek society.

This is all to say that, while Aristotle’s observations are savvy, they are rooted in a specific tradition and from a smaller window of human time.

The Three-Act Structure is not the only way to scaffold a successful story—evidenced by the large body of storytelling that is recorded around the world. Nonetheless, the Greek tradition anchors much of the Western canon, and many of the ways we approach storytelling can be traced directly back to Aristotle’s time.

Breaking Down the Three-Act Structure

So, what are those three acts, and what has to happen in them?

Act 1: The Story’s “Why”

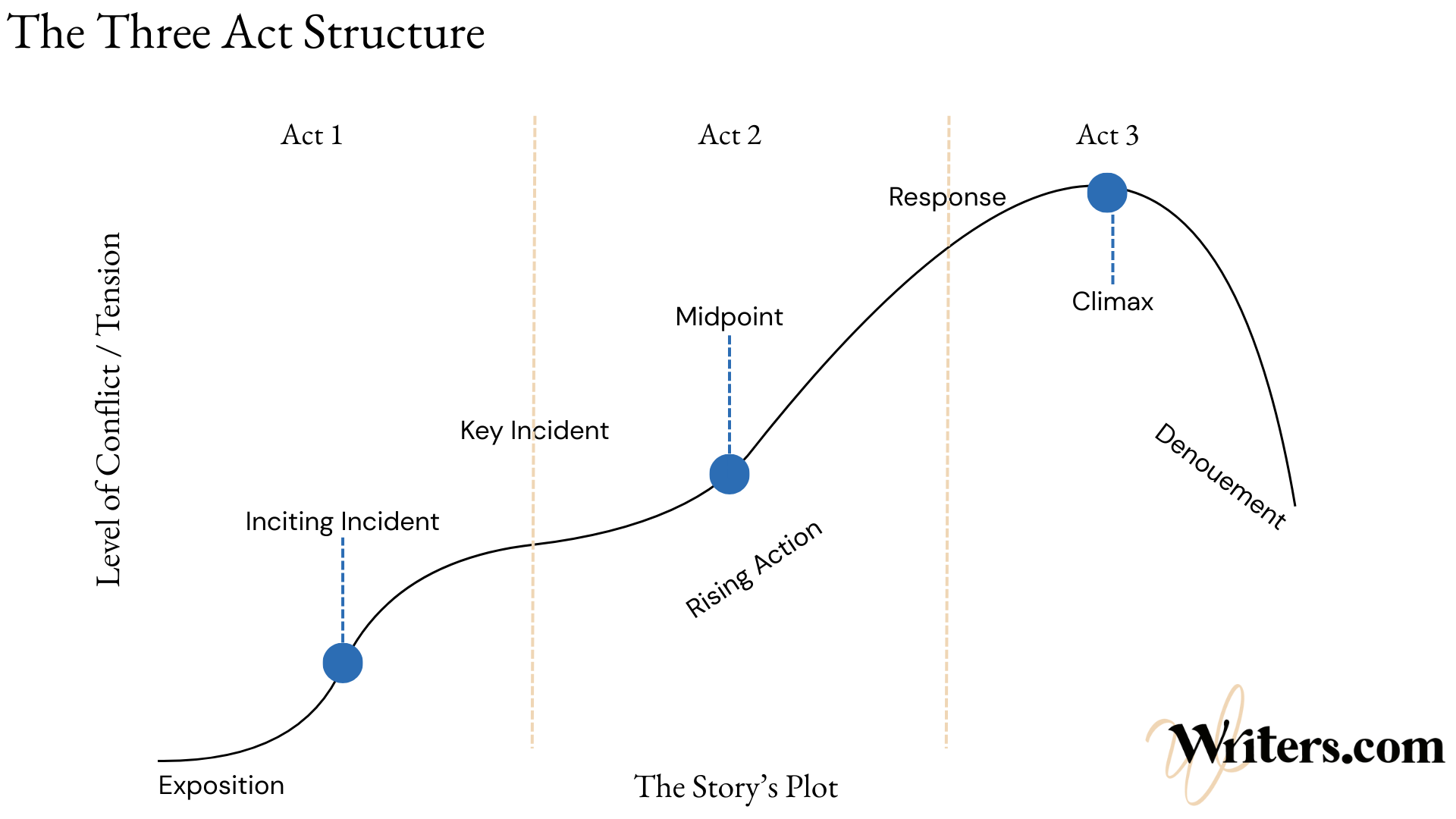

The first third of a story in the three-act structure involves:

- Exposition

- The Inciting Incident

- The Key Incident or First Plot Point

Act 1 tells us who the characters are: the protagonist, the antagonist, and the major players in the story. It determines what the protagonist wants, what they need to do to get it, and what stands in their way. It also tells us some of the protagonist’s backstory, the world they live in, and what their flaws might be. These essential details comprise the story’s “exposition.”

Act 1 determines what the protagonist wants, what they need to do to get it, and what stands in their way.

Sometimes the inciting incident begins on page 1, sometimes it comes a little later. In either case, the inciting incident is what propels the story into motion: it is the key event that makes all of the other events happen—the first in a long line of falling dominoes. Think: the onslaught of an alien invasion, or a murder most foul. Sometimes, it is as simple as two people meeting.

A key incident is the moment in which the protagonist actually decides to go on the journey initiated by the inciting incident. So what if aliens are invading planet Earth—I still need to decide if I’ll fight them.

Act 1 ends when the protagonist first acts as a result of the inciting incident. Sometimes, this is the same as the key incident. Other times, they key and inciting incidents coincide, and Act 1 finishes with the protagonist’s setting off on a journey (either literal or metaphorical).

Act 1 finishes with the protagonist’s setting off on a journey.

The keyword here is agency. Even if the protagonist does not want to go on this journey, they must exert agency and act in accordance with what the story asks of them. Only here does the plot, as they say, thicken.

Act 2: The Story’s “What Then?”

Act 2 in the three-act structure includes:

- Rising Action

- A Midpoint Event or Complication

- A Response to the Midpoint Event

Many of the terms in this plot structure, including “Rising Action,” are borrowed from Freytag’s Pyramid, which in turn was adapted from Aristotle’s plot triangle, first developed in his Poetics.

The Rising Action describes how tension ratchets up with the story’s escalating conflict.

The Rising Action describes how tension ratchets up with the story’s escalating conflict. It is the set of attempts and failures, of pushes and pulls, of forwards and backs that occur on the protagonist’s journey towards their object of desire.

This escalation inevitably reaches a Midpoint which further complicates the story, or else suggests to the protagonist that their goal cannot be met. The aliens are impervious to human weaponry; the murder is impossible and thus cannot be solved.

Whatever the complication, the Midpoint makes the possibility of failure much more real to the protagonist, who must decide how to proceed. If failure is not an option, then self-sacrifice may be the only way forward.

In any case, Act 2 ends with the protagonist responding, either physically or mentally, to the Midpoint event.

In any case, Act 2 ends with the protagonist responding, either physically or mentally, to the Midpoint event. Often, this involves a renewed faith in their journey or mission, or some sort of external reinvigoration that tells the protagonist hey, there’s still a way forward.

Act 3: The Story’s “What is Learned”

Act 3 in the three-act structure includes:

- A Pre-Climax

- The Climax

- The Denouement/Resolution

The protagonist is determined to pull off one last gambit to achieve whatever their goal is. The events leading up to this gambit are a kind of “pre-climax”—as is much of the story overall. These events lead to the climax of the story: the decisive event which determines the outcome of the story and the protagonist’s struggle.

The protagonist is determined to pull off one last gambit to achieve whatever their goal is.

The climax is often the most memorable moment of a story. The epic showdown between enemies; the jarring, unexpected decision a protagonist makes to determine their fate. The aliens are driven away from planet Earth, or the murder is solved by a stroke of divine intervention.

Once this happens, the story has the option of exploring the aftermath of the climax. Most stories do, though sometimes a story does end right at the climactic moment. In any case, what comes next is called the denouement, in which the fallout of the climax is explored until the story’s loose ends and plot threads are tied up.

The end does not need to tie up all the loose threads, nor does it need to resolve every conflict or idea—plenty of great stories end in ambiguity. But a successful denouement will add some thematic weight to the story, showcasing the outcome of the conflict of ideas.

A successful denouement will add some thematic weight to the story, showcasing the outcome of the conflict of ideas.

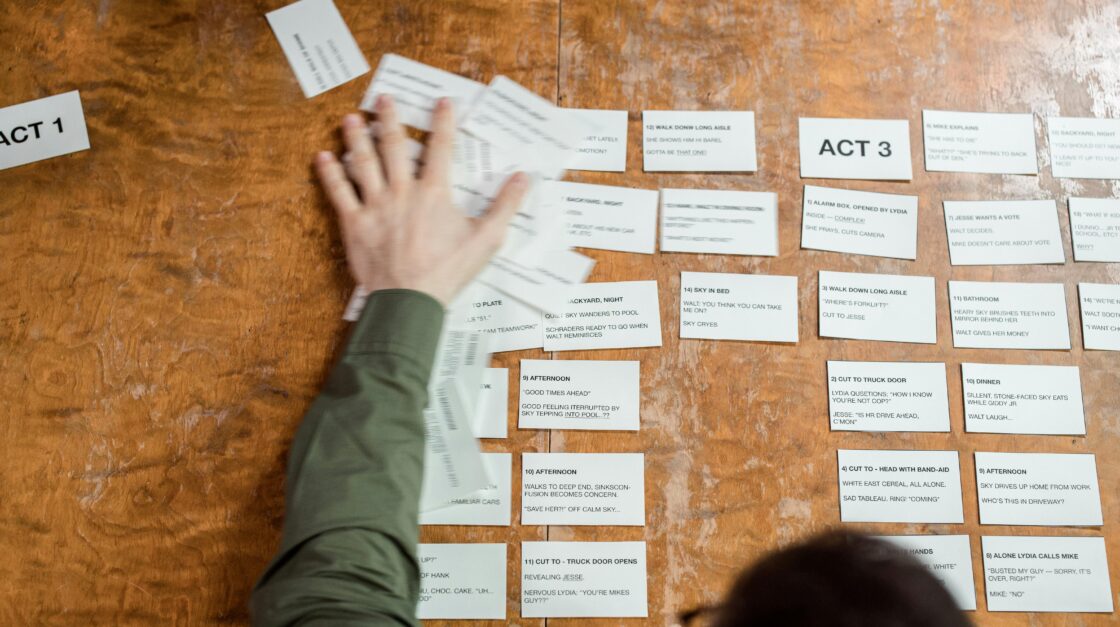

The Three-Act Structure Visualized

The below diagram maps out the above structure visually.

Three-Act Structure Examples

Let’s look now to some three-act structure examples. The three-act structure can be tailored to its story, but you’ll find the same structure persists throughout different media. Here’s a look at the three-act structure in film, on stage, and in literature.

Three-Act Structure Example in Film

The film Titanic presents an interesting use of the three-act structure, as the most memorable conflict—that of the iceberg sinking the ship—is one which the characters have no control over. Sure, the iceberg might be a kind of antagonist, but not the kind that the protagonists can actually fight.

It is within this setting that the film explores love, life, and the meaning of tragedy. Here are the major plot points that shape the story’s three acts:

- Act 1:

- Exposition: Exposition tends to work differently in films, as so much of it occurs at the visual level: settings, costuming, human expression, etc. We learn about the characters based on how they are presented to us. However, some exposition we receive includes the opening scene of treasure hunters exploring the wreck of the Titanic, and of Rose watching the report of it. The treasure hunters are searching for a necklace that Rose wore.

- Inciting Incident: Jack and Rose meet—at a moment when Rose is contemplating suicide, as she is unhappy in her engagement to Cal, but is forced into it by her mother.

- First Plot Point: Rose falls in love with Jack, obviously at the risk of her engagement and family relations. Jack draws a nude portrait of Rose.

- Act 2:

- Rising Action: The Titanic hits the iceberg.

- Midpoint: Cal discovers the nude portrait. He frames Jack for a theft and has him arrested.

- Response to Midpoint: People start to board lifeboats; Rose jumps back onto the ship to save Jack, to Cal’s chagrin.

- Act 3:

- Pre-Climax: Jack and Rose reunite but are both at risk of drowning on the boat.

- Climax: Jack ensures Rose is safe floating on the ship’s debris and soon dies. He asks Rose to live her life to the fullest in his absence.

- Denouement: We return to the present, with an aged Rose having reflected on the whole story. She turns out to still own the necklace the treasure hunters were after; she drops the necklace on a boat sailing above the wreckage of the Titanic. She imagines a world in which a young version of herself reunites with a young Jack.

Three-Act Structure Example on Stage

Stageplays offer an easy analysis of plot structure, as they are organized by acts and scenes. Some, like many of Shakespeare’s plays, occupy 5 acts instead of 3. Nonetheless, a three act play makes for a useful understanding of the three-act structure. Let’s see it in action in the Tennessee Williams play Orpheus Descending.

- Act 1:

- Exposition: We get a lot of exposition from Dolly and Beulah, two town gossips who don’t do much for the plot but do tell us how the judgmental small town feels about its cast of characters—including Carol Cutrere, a disgraced daughter of a wealthy family, and Val, the story’s hero.

- Inciting Incident: Val, a traveling musician, walks into a dry goods store. He is charming and attractive and mysterious. Carol Cutrere swears she recognizes Val from somewhere.

- First Plot Point: Val convinces the store’s manager, Lady, to hire him so that he can settle down somewhere.

- Act 2:

- Rising Action: Val’s naturally promiscuous nature creates tension between him and some of the other townsfolk. Lady thinks the way he walks and moves is intentionally erotic. The men don’t trust Val because of his charisma.

- Midpoint: A sheriff visiting Lady’s dying husband Jabe, the store owner, sees Val singing to Lady and suspects they’re flirting. The sheriff makes clear to both that he’s seen the two of them acting intimately with one another.

- Response to Midpoint: Val borrows money from the store cashbox and gambles with it, successfully. He tells Lady he’s leaving town, but, after an emotional conversation, she convinces him to stay.

- Act 3:

- Pre-Climax: Jabe reveals to Lady that he killed her father. The same sheriff who saw Val and Lady flirting sees his own wife, Vee, with Val in the store. They aren’t flirting, but the sheriff walks in on them believing they were, and tells him to leave by sunrise. Jabe’s nurse tells Lady, with Val listening, that Lady is pregnant.

- Climax: Jabe, who must have overheard at least parts of the above commotion, totters down the stairs from his bedroom and shoots Lady. He yells out that Val killed Lady and is looting the store; nearby men chase and kill him. (Orpheus, just when he has saved Eurydice by giving her the gift of new life, is now dead alongside her.)

- Denouement: Carol Cutrere soliloquizes about the ephemeral nature of fugitive things, reflecting back on both Val’s presence as a traveling musician and on the unexpected conditions of love and death.

Three-Act Structure Example in Literature

The three-act structure is easier to analyze in scripts, especially plays that are explicitly written in three acts. But the same structure applies to literature, so let’s see it in action in Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird—which is not a plot driven novel, but is nonetheless tightly plotted.

Note that the three-act structure works a bit differently in a literary novel like this one. The novel is told from the perspective of a child who is not directly involved in the story’s main events. So, ideas like inciting incidents and midpoints are a bit hard to adapt to a novel like this one, because the children themselves are not on a conventional protagonist’s journey with their own agency.

Nonetheless, a novel that’s difficult to pin to the three-act structure helps better expose the structure’s workings.

- Act 1:

- Exposition: The novel has loads of exposition. The narrator is Scout Finch, an elementary school child, speaking to us from an older age. We need to understand the social dynamics of Maycomb, a small town in Alabama, so that the story’s conflicts make sense within the setting.

- Inciting Incident: Scout’s father, Atticus, has agreed to defend a Black man, Tom Robinson, in a rape trial against the Ewell family. [Note: Scout is the protagonist and narrator of the novel, observing the world as she learns about it through Tom Robinson’s trial. The inciting incident nonetheless incites a conflict she is not directly involved in, but does become affected by.]

- First Plot Point: Atticus moralizes to Scout and Jem that it’s important for him to do the right thing and defend Tom even if it brings his family discomfort. As a result, Scout chooses not to fight a school bully who mocks her for her father’s morality—the first time she willingly doesn’t fight someone (and thus consigns herself to the moral conflicts of the story).

- Act 2:

- Rising Action: Scout and her brother, Jem, are mocked by their neighbors for having a father who defends a Black man in court. In one instance, Jem destroys his neighbor’s flowers; his father forces him to read to his neighbor every day for a month.

- Midpoint: Atticus faces a lynch mob outside the county jail who want to kill Tom before the trial starts. Jem and Scout have followed Atticus without him knowing; Scout gets into an argument with one of the lynch mobbers, and her own moralizing breaks up the mob.

- Response to Midpoint: The response to this midpoint event is unconventional: namely, the midpoint threatens to prevent the trial from happening, so the response is simply that the trial happens as planned. Nonetheless, Scout learns something about morals, about mob mentality, and about the thin, beating humanity that can prevent even the most blind racist mob from killing a Black man.

- Act 3:

- Pre-Climax: Much of the novel centers around the trial of Tom Robinson. Atticus does not want Jem and Scout to attend, but they do anyway. Atticus is eloquent and exhibits sound rhetorical strategies. It turns out that Mayella, who is accusing Tom of raping her, actually made sexual advances towards Tom; her father, Bob, disliking this, beats Mayella and then has Tom arrested. Despite Atticus clearly demonstrating that Tom did not rape Mayella, Tom is convicted; later, he tries to escape from prison and is killed.

- Climax: The Ewells have been humiliated by the trial, even though they won. As a result, Bob Ewell swears revenge on Atticus and eventually attacks Jem, but does not succeed in killing Jem, due to the unexpected intervention of a reclusive neighbor. Bob is then killed.

- Denouement: With no clear understanding of what happened, Maycomb’s sheriff agrees to call Bob’s death an accident, and Scout imagines what life must be like from the perspective of the neighbor who saved Jem—a testament to the novel’s theme of empathy.

Is the Three-Act Structure Universal?

The three-act structure is a useful tool for understanding the scaffolding of many successful stories. You can even use it to write your own novel. Nonetheless, this is not a universal plot structure—far from it.

The three-act structure is not universal.

If anything, the three-act structure suffers from a lack of granularity. In mapping the above stories to this plot form, so many details, themes, and characters are inevitably discarded. Moreover, the plot structure requires a summaristic understanding of the conflicts that shape and propel a story towards its climax. Much is left out as a result.

Other forms of plotting, such as Freytag’s pyramid, “Save the Cat,” and the Snowflake Method each get into the weeds of effective storytelling—though these stories, of course, can also map back onto the three-act structure.

Short stories and flash fiction, by the way, don’t need a three-act structure at all. They are, by way of their concision, moments and ephemera: often driven by conflict, yes, but not with the bells and whistles of these longform plot devices.

Additionally, conflict is not the only way to structure a story. Most Western plot structures, including this one, are propelled forward by conflict. A counterexample that comes from Japan is Kishōtenketsu, a four-act structure organized around the unfolding and understanding of human events.

Finally, you’ll find that the three-act structure, as well as other conventional plot structures, is best applied to works of genre fiction. Genre fiction’s use of tropes and plot conventions allows the writer to explore ideas and themes through familiar storylines. This is not to say that genre fiction is inherently superior or inferior to its seeming opposite, “literary fiction”—only that the three-act structure is less likely to be subverted or interrogated in genre works.

More Resources for Plotting

For more applications of the three-act structure, as well as other ways of thinking about plot, read our resources for fiction writers:

- What is the Plot of a Story?

- Subplots in Fiction

- How to Write a Story Outline

- Understanding Story Structure

Write with the Three-Act Structure at Writers.com

Want to structure your novel, screenplay, or story—and need help along the way? Check out the upcoming fiction writing courses at Writers.com, where you’ll plot and write your best stories yet.

Your articles are always accessible, unlike some well-intentioned coaches.

Thank you.

I learned a lot. Thank You!

This was hugely insightful and beneficial – thank you so much for sharing your expertise!