Learning how to write poetry takes a lot of patience and practice; learning how to get poetry published does, too. Indeed, the world of publishing poetry is murky at best—with seemingly countless outlets to get published in, a culture of unspoken rules and ideas, and a mountain of rejections to climb.

This article is your guide through the poetry publishing process. While it’s impossible to explain every corner of the literary universe, we can confidently guide you through the following:

- How to set, achieve, and exceed your poetry publishing goals.

- What markets out there for poetry journals.

- How to publish a poetry book, and what the publishing landscape looks like.

- The differences between traditional and self-publishing.

- Where to keep up with the contemporary poetry publishing world.

So let’s get into it, and let’s start with what you need to know about the poetry publishing industry.

How to Get Poetry Published: Contents

- What to Know About Publishing Poetry

- How to Get Poetry Published in Literary Journals and Anthologies

- How Poetry Journals Work

- What is the Process for Submitting to Poetry Journals and Anthologies?

- What to Include in Your Title, Cover Letter, and Third-Person Bio

- What Counts As Previously Published Poetry?

- Where Can I Publish Poetry?

- What Happens When I Get A Poem Accepted?

- Other Tips on How to Get Poetry Published

- How to Get Poetry Published: Chapbooks and Full-Length Collections

- What is a Chapbook? What is a Full-Length Collection?

- What Length Should My Poetry Collection Be?

- The Different Avenues of Publishing Poetry Collections

- Do I Need An Agent to Publish a Poetry Book?

- How Do I Publish Poetry With The Big 5?

- Where Do I Find Traditional Publishing Opportunities?

- How Much Money Do Poetry Books Make?

- Is My Published Poetry Copyright Protected?

- How to Get Poetry Published: Defining Your Goals

How to Get Poetry Published: What to Know About Publishing Poetry

The best advice we can lead with is advice around the mindset of publishing poetry. Internalize a few things:

- The goal should not be to get rich or famous; neither are you trying to play up the singularity of your literary genius. These goals are unrealistic and not in the spirit of poetry.

- The poetry world can seem impenetrable, but if you see yourself as being in conversation and community with fellow poets, it is actually a lot easier to find your niche and lineage.

- Your work is worthy of readership.

The truth is, publishing poetry often involves a lot of rejection. Career poets who regularly submit to journals might have a poem rejected 20 times before it gets published—and more than 20 if they’re focusing on prestigious, exclusive journals. Even poets who simply want their work in the world have to anticipate rejection, not because the work is “bad,” but because there are a lot of poets trying to publish and not enough spaces for publication.

Poets who simply want their work in the world have to anticipate rejection, not because the work is “bad,” but because there are a lot of poets trying to publish and not enough spaces for publication.

Why Do Poetry Submissions Get Rejected?

Later in this article, we offer tips and insights on getting your poetry published. But I want to first address what is often the most painful part of poetry publishing: rejection letters.

Every poet gets their work rejected.

Every poet gets their work rejected. The few poets who are regularly publishing in prestigious journals also trudged through countless rejections before achieving their present status. This is true for both poetry journals and manuscripts—recently, a well-published poet told me that every poem in her manuscript has been published, but the manuscript itself has been rejected dozens and dozens of times. Publishing is fickle.

So, why do poetry submissions get rejected? And what can a poet do about rejection?

Very often, a submission gets rejected not because of the caliber of the work, but because of one or more of the following reasons:

- It doesn’t match the editors’ tastes. The key word is “taste,” which is a rather arbitrary and individual standard for what a person likes and doesn’t like. It doesn’t mean your work is “bad,” only that the editors are interested in other kinds of work. A good way to get a sense of the editors’ tastes is to read previous issues of the journal (which you should be doing anyway!)

- The work is good, but the journal received a lot of good submissions. This is going to happen to you very often. The editors will think your work is good, but select other work for publication—probably, again, because of taste.

- The journal is oversaturated with your kind of work. Maybe you submitted a free verse poem about how much you love the countryside, and the journal has received 10 good poems in the past 3 months about free verse countryside love. Either the journal becomes the headquarters for that type of poem, or, far more likely, they select one poem and gently reject the rest. (Yes, this happens a lot more often than you’d think.)

- You didn’t follow the rules. Be sure to follow the journal’s guidelines for publication. If the journal doesn’t accept simultaneous submissions, do not submit simultaneously; if the journal wants your poem in Times New Roman 12pt font, yes, they might reject your work for being in Garamond.

Sometimes a rejection does have to do with the caliber of the work—but this is not something to take personally. I look back on poems I had received rejections for years ago, and think, oh, of course it got rejected. Every poet with a writing practice matures in their work, and the poems I thought were killer when I was 20 are, quite frankly, paltry at best with years of hindsight.

What hurts is that you often don’t know why a poem was rejected. Is it a matter of taste, or does the work suck?

Your work is worthy of readership.

I refer you back to the above mindset advice, particularly #3: Your work is worthy of readership. This is true even if it doesn’t match someone’s taste, even if it isn’t the highest caliber—a quality which, quite frankly, is also a question of taste, because there is no true arbiter of what “good” and “bad” poetry is.

If you want to expand your understanding of poetry craft, you might be interested in the following links:

- Upcoming poetry classes at Writers.com

- How to write a poem

- What is form in poetry?

- What is poetry?

- How to Become a Poet

So, with all this being said, let’s look first at how to get poetry published in literary journals, before also looking at the publishing of poetry collections.

How to Get Poetry Published in Literary Journals and Anthologies

Before I offer advice on publishing in poetry journals, it occurs to me that many poets don’t know how poetry journals even operate. So let’s demystify this black box first before sharpening up your poetry submissions.

How Poetry Journals Work

What happens when you submit your poetry to a journal?

Typically, your submission packet goes through a few rounds of readers, including:

- First, the Submissions Readers. These are volunteer readers who read through all of the submissions that the journal receives. Sometimes, one reader alone makes the decision on whether to further consider your submission; often, a submission will be read by 2 or more readers before any decision is made. Submissions that readers deem worthy of consideration then go on to the Genre Editor.

- Second, the Genre Editors. In this case, the Poetry Editors. Poetry Editors read through the submissions that have been winnowed down by the Readers. They make further decisions on what work to seriously consider for publication. Some journals have a single Poetry Editor, some have multiple.

- Third, the Editor-in-Chief. The Poetry Editor(s) then bring the poems they’re most interested in publishing to the Editor-in-Chief, who makes the final decisions (alongside the Genre Editors) about what poems to publish. Often, these decisions include how the poems they publish can be in conversation with each other, or even be in conversation with the fiction, nonfiction, and artwork that the journal is also considering for publication.

This process sometimes takes 24 hours; sometimes it takes 8 months or longer. The more people are involved, the longer the process takes—and the more “tastes” have to be appeased by the work, though this process also ensures that higher-caliber work is more likely to be noticed.

What is the Process for Submitting to Poetry Journals and Anthologies?

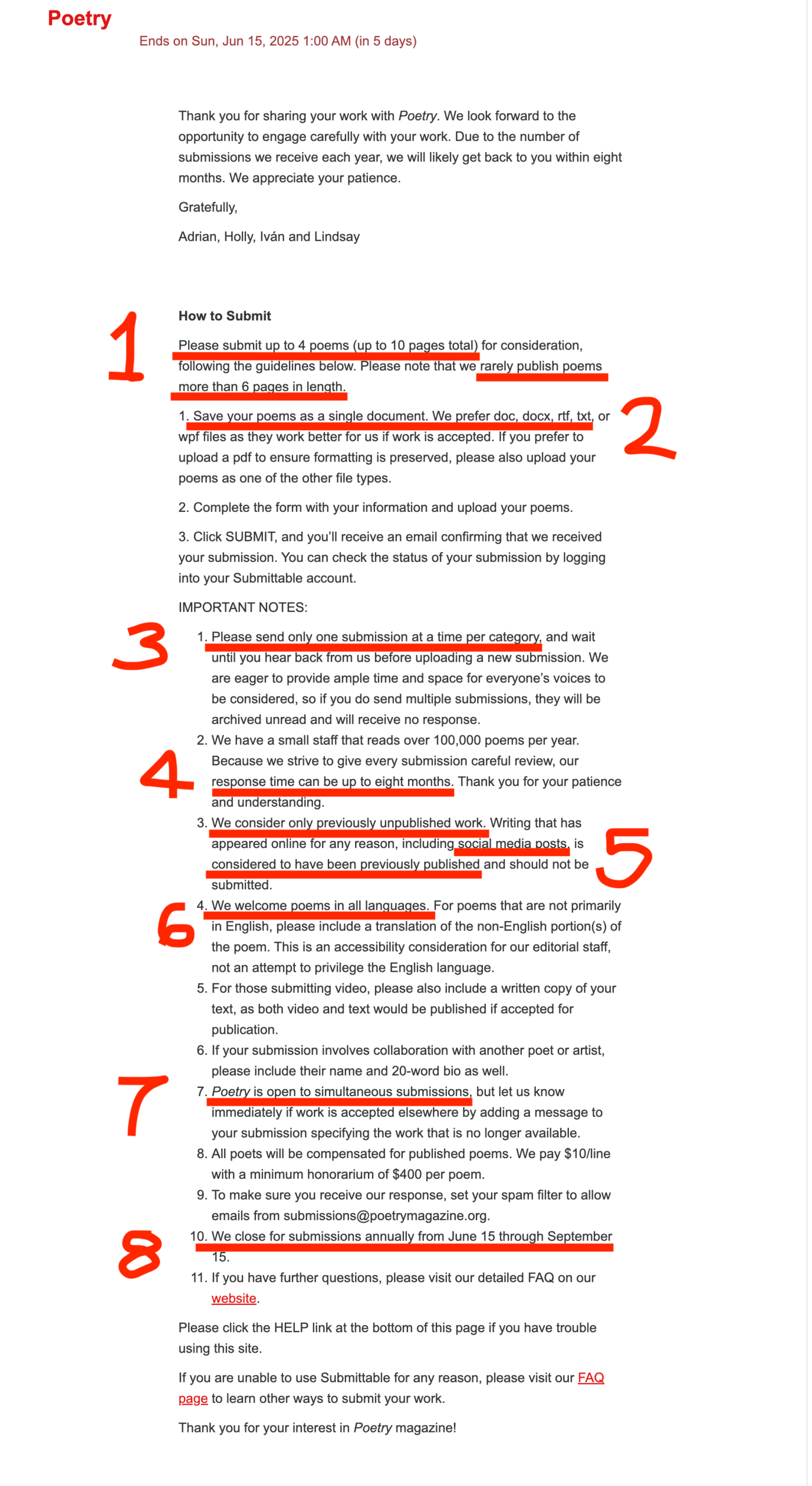

Every journal lays out its own processes and guidelines for submitting to them. Let’s go through the guidelines of POETRY together.

A poetry journal’s submission guidelines typically answer the following:

- How many poems/pages you can submit. (This sometimes includes preferred fonts and sizes.)

- The document format. (.docx is always a safe option.)

- How frequently you can submit to the journal.

- How long you can expect to wait for a response.

- Restrictions on previously published work (and how the journal defines that).

- Language restrictions.

- Whether the journal allows simultaneous submissions—in other words, if you can submit the same poem(s) to other journals.

- When the journal is open/closed.

Most literary journals accept digital submissions. Some still accept mailed submissions by SASE. In all cases, the instructions for submitting are clear on each journal’s website. For digital submissions, many journals use submission managers like Submittable, Moksha, or Duotrope, or they take submissions via email.

What to Include in Your Title, Cover Letter, and Third-Person Bio

When you submit your poems to a journal, you will be asked for a title cover letter and bio. This often stresses new poets out.

For most journals, this is simply a way to introduce yourself and your work. Most journal editors don’t make serious judgments off of the cover letter, so long as it’s written well and adheres to any guidelines they state.

Most journal editors don’t make serious judgments off of the cover letter, so long as it’s written well and adheres to any guidelines they state.

Some journals specify what they want your Title to be. If they don’t, here’s a tip: make your Title a list of all the poems you are submitting. For example: “Poem 1, Poem 2, Poem 3, Poem 4.” (Hopefully you can come up with better titles than me.) This makes it easier to track what poems you have submitted where, and a good title might generate intrigue for the submissions readers, too.

Your cover letter should include a few items:

- An address to the editors.

- “Dear Editors” often suffices, though you might stand out if you address the Editor-in-Chief or guest editor.

- What your submission includes.

- This can be as simple as “four poems” or the title of your poem(s).

- Optionally: if this is a simultaneous submission.

- DO say if you’re submitting these poems to other journals. It’s an act of courtesy.

- Optionally: what project or collection the submission is a part of.

- This can build interest in the work or frame the work that the editors are about to read.

- Optionally: trigger warnings.

- If your work includes sensitive content that might upset certain readers, it’s best to let them know.

- A third-person bio.

The third-person bio can include your publication history (if any), where you live, what you do for work, a fun fact about yourself, or none of the above. Again, it’s rarely serious: you’re just making a brief connection.

Here’s an example of the message I typically send when I submit poems to journals:

Dear Editors,

I hope you’re well! I have included 6 poems for your consideration. These poems are part of an ongoing collection of work exploring queerness, outsiderness, and monstrosity.

This is a simultaneous submission. I admire the work you publish at [Journal Name] and am grateful to have my work considered by you.

Please note, there is a content warning for homophobia in this submission.

I appreciate your attention to my work!

Warmest,

Sean Glatch

Bio:

Sean Glatch is a queer poet, storyteller, and screenwriter in New York City. His work has appeared in Ninth Letter, Milk Press, 8Poems, The Poetry Annals, on local TV, and elsewhere. Sean currently runs Writers.com, the oldest writing school on the internet. When he’s not writing, which is often, he thinks he should be writing.

What Counts As “Previously Published” Poetry?

Most literary journals do not accept submissions of previously published poems. They will state this explicitly in their guidelines if so. (A few do accept or even encourage republication, and poems are often republished in anthologies.)

“Previously published” can be a bit poorly defined, however. Does it count if I posted an early draft on my blog or Instagram? What if I shared the first four lines of the poem on a random podcast? Can I just delete the post so that the poem is again unpublished?

If your poem shows up in a publicly accessible space, that counts as being previously published.

Here are some basic guidelines:

- If your poem shows up in a publicly accessible space, that counts as being previously published. This includes any form of media, social or otherwise. If the poem appeared on your blog, in an Instagram picture, on a video recording on YouTube, etc., that counts as “published.”

- This is true even if the poem you submit to that journal has undergone moderate revisions since it was first posted. If the poem has undergone a major overhaul, in which the final draft is significantly different, then it may count as being its own unique poem, though this can only be determined on a case-by-case basis.

- This is also true even if only a portion of the poem appears somewhere publicly.

- Deleting your poem may technically “unpublish” it, though the poem still has been “previously published.” Technically, if you can guarantee your poem doesn’t appear anywhere after the post has been deleted, you’re in the clear to submit it to a literary journal.

- That said, a lot of the literary world abides by an honor code. When you submit to a journal, you are tacitly saying that the poem has not been previously published. If you’re caught in that lie, you might be banned from submitting to that literary journal. Moreover, even if you can guarantee not being caught, it’s best not to act deceitfully at any point of your writing career.

- “Will I get caught if I submit anyway?” It really depends. Bigger name journals, like The New Yorker and POETRY, certainly commit rigorous research and fact-checking before they publish anything. But that doesn’t mean you should test your fate with smaller journals—most writers are internet-savvy enough to find a poem’s previous publication, and again, you want to conduct yourself honorably in all writing spaces.

Some literary journals make a distinction between “previously published” and “previously curated” poems.

Some literary journals make a distinction between “previously published” and “previously curated” poems. Those journals, like ONLY POEMS, make clear what they mean by this in their submission guidelines. Basically, a poem is “curated” when it’s accepted for publication by a journal or magazine that curates and organizes literature. Your work isn’t being “curated” by an editor when you publish something on your own social media, so these kinds of journals accept previously posted work, so long as only you have posted it on personal accounts.

In short: act honorably, don’t push your luck, and treat literary journals with the same trust and dignity as you want them to treat you.

Where Can I Publish Poetry?

The internet is filled with databases and catalogs of journals publishing poetry. Here are some places we recommend to look:

- Our article on literary journals publishing poetry

- The Submittable Discover Page

- Chill Subs (Well organized and accessible for new poets)

- Authors Publish (Good for opportunities in all genres)

- New Pages

- The P&W Database (some journals may be defunct)

You can also keep up with literary journals and publishing opportunities through social media.

When you consider submitting to a literary journal, read their past work and any statements they make about the kind of work they’re looking for.

When you consider submitting to a literary journal, read their past work and any statements they make about the kind of work they’re looking for. These statements are often nebulous, but they give you a sense or vibe of what they want, and can help you determine whether to submit to them or not. (Of course, the worst thing that can happen when you submit is that you receive a rejection, though this can be a bit more frustrating if you paid money to submit to the journal.)

What Happens When I Get A Poem Accepted?

A literary journal’s acceptance of your poem will include the following:

- Details about when the poem will be published.

- Information about where and how the journal will pay you (if they are a paying publisher—many journals are not).

- Language confirming that the journal gets first rights to your poem’s publication. Often, this includes a form or request for the poet to consent to this.

When a poetry journal accepts your poem for publication, be sure to do the following:

- Send a brief note of gratitude to the journal that accepted the poem.

- Notify other journals you submitted the poem to, as they will now not be eligible to publish it.

- Throw a party. Print your poem and put a little party hat on the poem. Ask everyone at the party to give the poem a little kiss. Congratulations! Your poem will be published!

Other Tips on How to Get Poetry Published

Here are a few other pieces of advice as you navigate publishing poetry in literary journals.

- In your submission packet, make sure that a new poem begins on a new page. Do not fit multiple poems onto one page to save space. New poem; new page.

- This goes without saying, but do not plagiarize. If your poem is inspired by an existing published poem, credit it by saying your poem is “After [Poet]”. If your poem borrows lines from another poem or work, credit that, too.

- This also goes without saying, but speak respectfully to every journal and editor you interact with. There are too many horror stories out there about a journal rejecting someone’s work, and the writer replying back about how the journal is blind to genius, etc. Don’t be that person.

- On the flipside: do understand that literary journals sometimes act poorly, too. They might not respond to your submission. They might not respond to your nudge about the submission. They might respond poorly to you nudging them on your submission, even though their guidelines said you could do that. When this happens, treat it as the journal’s loss, because it is.

- Do not worry too much about prestige. Sure, you might want to save your “best” work for a journal with a bigger reach—but, prioritize publishing in spaces where you want your work to be seen, where you feel like your poetry is in conversation and community with the other poets and readers.

How to Get Poetry Published: Chapbooks and Full-Length Collections

The process for publishing a poetry collection shares many similarities to the process for submitting to journals. So, much of the same advice applies: follow the submission guidelines, lead with kindness, don’t take rejections to heart, etc.

The process for publishing a poetry collection shares many similarities to the process for submitting to journals.

The bulk of this section will explain the different facets of poetry book publishing. We will also include places to look for publication opportunities and advice specific to the publishing of poetry books.

This article does not offer insight on the craft of poetry books themselves. If you would like to learn more about composing a poetry book, check out these articles:

What is a Chapbook? What is a Full-Length Collection?

First and foremost, there are a few different categories of poetry collections, distinguished by length. The breakdown is as follows:

| Collection | Length | Description |

| Microchap | 8-12 poems, no more than 12 pages in length | A very short group of poems

tightly concentrated around a particular idea or theme. Often free or very cheap. |

| Chapbook or pamphlet | Up to 47 pages | A short collection of poems navigating a few themes or ideas. Typically inexpensive. |

| Full-length | 48+ pages | A collection of poems that navigates a group of ideas, tells an extended story, and/or employs certain experiments in poetry craft.

Prices vary by publisher and prestige. |

What Length Should My Poetry Collection Be?

In truth, there’s no predetermined path for the publishing poet. Some poets put out a number of chapbooks before publishing their first full-length collection; others dedicate themselves strictly to the full-length.

It’s much better to decide on the length of your collection based on what the work itself demands. Ask yourself:

- Do you feel as though your collection has fully explored the themes and ideas that bring your poems together?

- Does your collection present a complete portrait, exploration, or understanding of its central questions?

- Conversely, does your collection have different poems that say the exact same thing, or act as “filler” just to make the collection feel longer?

- Can I identify what each poem brings to the collection that is unique and essential?

These questions can help you think through the length of your book as you move towards putting collections of poetry into the world.

The Different Avenues of Publishing Poetry Collections

Poets will typically submit their manuscripts to one of the following opportunities:

Open Reading Periods

Publishers that routinely publish poetry books often have open reading periods. These are periods where poets can submit manuscripts to the editors of the press, and those editors typically make the final decisions.

Open reading periods:

- Are typically cheaper to apply to, though poets may still have to pay a reading fee.

- May be capped at a certain number of submissions, depending on the editors’ bandwidths.

- Often result in multiple poetry collections being accepted for publication.

- May be seen as less prestigious or offer less money in the publishing contract.

Contests

Many poetry publishers also put out annual or regular contests. A contest is usually judged by a well-regarded poet. This poet reviews only the Finalists in the contest, and the Finalists are selected from the readers of the poetry press.

Contests:

- Typically have submission fees between $20-$40. These fees go towards paying the press readers, the guest judge, and funding the prize of the contest.

- Include prize money for the winner(s). Sometimes the prize is as low as $500, sometimes it’s as high as $10,000.

- Often result in only one collection being accepted for publication. Some presses may consider other Finalists for publication, but this is not guaranteed.

- Can be a source of prestige or accomplishment for the winner(s). The guest judge who selects the book for publication will also usually write a blurb that promotes the book.

Self-Publishing

Given how many poets want to publish collections, and how few opportunities there are to get published, some poets turn towards self-publishing presses to put their work into the world.

Self-publishing:

- Is typically low-cost. You may end up paying someone to design the book cover or to typeset the collection, but you can also do this yourself.

- Requires a lot of self-promotion. If you want to be well-read, you have to promote the collection yourself. This is also true for traditionally published poets, but those poets benefit from the modest marketing networks that poetry presses might have.

- Comes with higher royalties per sale. You will have to pay the press for each print of the book, but you still stand to make more money per-sale than you would through a traditional publisher. (Of course, there is no advance payment or award money for self-published poets.)

- Is typically viewed as less prestigious. Poetry publishers are also gatekeepers of the poetry world, as they’ve done the work of vetting what collections merit publication, and also have editors to work with the poet as the book gets shaped up for publication. Self-published authors lack institutional backing, as well as the professional design and typesetting services that poetry presses offer. This is not to say that self-published books are inherently “less good” (again, an arbitrary standard of taste)—it’s to say that self-published poets sometimes have bigger hurdles to jump for their work to be bought and appreciated.

There are different companies dedicated to self-publishing books, including Lulu and KDP (an Amazon platform). You can learn more about self-publishing here:

We don’t advocate for any particular avenue of publication—each has its pros and cons, which are better determined by your own goals for publishing poetry. We do, however, caution against the use of vanity presses, which are publishers that you pay to have your book published. Vanity presses claim to offer support, professional marketing, and higher book design capabilities—but these claims are often exaggerated, with poets paying money they never recoup for a final product that they could have published themselves.

Do I Need An Agent to Publish a Poetry Book?

No! Literary agents typically only represent fiction and nonfiction, anyway. The only time you would need an agent is if you wanted to publish a collection with The Big 5—and the only way an agent would represent your poetry collection is if you were already famous. Most poetry collections are published unagented.

Most poetry collections are published unagented.

How Do I Publish Poetry With The Big 5?

In truth, there are few opportunities for poets to publish with The Big 5 publishers. It’s not that these presses don’t put out poetry collections, it’s that they are very risk averse in taking on books that aren’t guaranteed to sell well, and poetry, in general, doesn’t sell well.

As such, Big 5 imprints typically only sell collections from well-established and famous poets, or else from celebrities who decide to publish poetry collections.

Where Do I Find Traditional Publishing Opportunities?

As with poetry journals, the internet is filled with databases for poetry presses accepting manuscript submissions. Here are some we recommend:

- Poets & Writers

- Submittable

- New Pages

- Authors Publish

- Poetry Bulletin

- Reedsy

- Driftwood

- The John Fox

- Publishers Archive

We also recommend that you keep up with poetry presses the same way you might keep up with poetry journals, and to follow publishers and publishing opportunities on social media.

How Much Money Do Poetry Books Make?

The unfortunate truth is that poets are unable to live solely off of the sales of their poetry books. Although some contests offer winnings of $10,000 or more, and although some publishers have robust marketing networks, there simply isn’t enough sustained readership of poetry, or enough people buying poetry books.

The unfortunate truth is that poets are unable to live solely off of the sales of their poetry books.

Indeed, a poetry manuscript that sells 1,000 or more copies is seen as performing very well in the publishing marketplace. The poets who sell this number of copies are typically well-known and well-published, with a strong following or email subscriber list. These poets also often have the support of poetry institutions, like universities, writing schools, or nonprofits that seek to champion contemporary poets.

This is why we encourage you to build community as a poet. Often, your readers are going to be the poets you’re in regular conversation with—and we of course hope you will buy the books of poets you know, too. The poetry community is what helps sustain poets more than anything else.

Additionally, business-savvy poets might use the publication of their book to:

- Apply for paid speaking engagements with schools and universities on the topic of poetry.

- Present themselves as potential poetry instructors.

- Sell themselves as coaches or mentors to poets looking for critical feedback and help.

- Apply for funding opportunities or prestigious titles, such as the MacArthur Grant or being a State Poet Laureate.

A poetry manuscript that sells 1,000 or more copies is seen as performing very well in the publishing marketplace.

There are few poets who are able to live entirely off of the work of poetry, but more opportunities are created as more poets join in the celebration and community of poetry.

Is My Published Poetry Copyright Protected?

Yes! Whether you publish in a journal, a poetry collection, an anthology; whether your work is traditionally published or self-published, including on social media—all published poetry is automatically copyright protected.

Poets & Writers has a great breakdown of copyright protections here.

In short:

- Poems published both in books and on the internet are protected automatically. Many poetry journals will request First North American Serial Rights (FNASR) on your work when they publish it, which grants them the exclusive right to first publish your poem, but does not strip you over your ownership of the work.

- Work published online also has protections due to Creative Commons laws, which specifies how work can be republished and with what contexts and consents.

- The risk of copyright infringement on your work is low. Plagiarism does happen in the writing world, and it can be hard to prove your work has been plagiarized, though scandals certainly happen. Registering your work with the U.S. Copyright Office can bolster protection of your work, though this is not a free service and often not worth the cost. It typically only makes sense to do this for work that is self-printed and self-distributed; all other forms of publishing come with some inherent copyright protections.

How to Get Poetry Published: Defining Your Goals

Publishing poets have a lot to think about. Knowing how to get poetry published is one thing, but figuring out where and why are difficult questions as well. If you find yourself uncertain of the path forward, it can be good to figure out your goals as a poet before trying to publish poems.

Here are a few sets of questions to help you figure out your poetry goals. There are no wrong answers!

Which is more important to you:

- Prestige or readership?

- Prestige comes with readership, but it’s much harder to build: prestigious journals and presses are often slower to respond and more likely to reject your work. Privileging readership means you might publish in less renowned journals, but make more connections faster.

- Poetry as a career or poetry as a community?

- Do you just want the connectivity of poetry, or are you trying to build up a portfolio of publications that can later become full-length manuscripts, teaching opportunities, and speaking gigs? A poetry career comes with community, but also takes a lot more work and dedication—and you probably have to care, at least nominally, about prestige and contests.

- Celebrity or community?

- Obviously, community precedes celebrity. But, are you looking to only find your niche of poets—your group of writers with similar interests, aesthetics, and/or approaches—or, do you want your work to be more widely celebrated in the poetry world and culture?

Again, there are no wrong answers to the above. Defining your goals will simply help you assess whether you want to submit to any particular journal or contest.

Here’s another set of questions.

Does your poetry:

- Have a stable set of influences? Do you find that your work draws on one or two lineages, or has a wide variety of voices informing it?

- This is one way of identifying a journal’s publishing interests. Most journals won’t say they’re explicitly affiliated with The New York School or the Confessional Movement, but you might notice that they often publish poems in the realm of New Formalism (for example).

- Focus on certain subject matter?

- There are journals dedicated to different topics: identity, climate, love, politics, free verse, etc. These are all ways of identifying publishing opportunities for your work.

- Speak to a certain audience?

- This is another way of narrowing down journals that might want your work.

- Converse with other contemporary poets?

- If you find your work is in lineage with contemporary poets, you may consider looking at the journals those poets have published in and submitting to those journals too.

Lastly, here are some questions about where you’re currently at as a poet.

Are you:

- A seasoned poet, or new to the craft?

- If you’re new to the craft, there’s a smaller chance your work will be accepted by prestigious journals. This isn’t to discourage you from trying (send it!), but simply to give you a reality check. Poets published in spaces like The New Yorker, The Paris Review, or POETRY typically earn these credits after years and years of working at their craft.

- An avid reader of poetry journals, or new to the lit mag world?

- If it’s the latter, make it a practice to read different journals. You’ll learn much more about contemporary poetry, and where your work fits in, from doing this than from doing anything else.

- Located in a city with a lot of poetry community, or located somewhere more remote?

- Cities like New York, San Francisco, Chicago, Washington, London, or Dublin offer more in-person opportunities for poetry community, including local literary journals. If you want to get offline and be in community in your area, start locally!

Do not mistake publishing as the “point” of poetry.

And lastly, remember that publishing is only one part of the poetry process. Do not mistake publishing as the “point” of poetry—it is a means of putting your voice into the world and being heard, but there are many ways to do this, and the legitimacy that publishing affords is not unique to publishing.

Learn How to Get Poetry Published at Writers.com

Whether you want to sharpen your craft, revise your poems, or learn the ins and outs of publishing, take a look at the upcoming poetry classes at Writers.com, where you’ll receive expert feedback and instruction on the process of being a poet.

Thank you for sharing this, Sean — it’s very helpful. As a new poet hoping to share my voice with the world and connect with a wider community, your article gave me a lot to reflect on. It helped me think more deeply about the why behind publishing, and how to navigate a path that aligns with my personal goals and current stage of growth.

Grateful for your insights — thank you!

Thanks for the much-needed information.

Thank you very much for this gems. It educating and enlightening