Flash nonfiction is an emerging literary genre that combines the concision of flash fiction with the truth-seeking qualities of creative nonfiction. By using as few words as possible to strike at the truth of something, flash nonfiction often leans into poetic language to say what it needs.

Do not mistake brevity for simplicity: a successful piece of flash nonfiction still incorporates complexity and insight into its small size. If you’d like to learn more about this genre, or learn how to write flash nonfiction, read on to discover this exciting form of CNF.

Flash Nonfiction: Contents

What is Flash Nonfiction?

Flash nonfiction is a work of creative nonfiction that, typically, is written in 1,000 words or fewer. This word limit mirrors the limits of flash fiction, which are fictional stories told in under 1,000 words.

Flash nonfiction is a work of creative nonfiction that, typically, is written in 1,000 words or fewer.

Alternate terms for this genre include “micro-memoir,” “flash memoir,” “flash creative nonfiction,” or “micro-essay.” Sometimes, “micro” genres are even smaller than flash—a maximum of 100 or 200 words, for example—but they bucket under this category of concise truth-telling.

Of course, what makes a flash nonfiction piece successful is not only its brevity. In order to tell a complete story about your own life, you will need to rely on the craft tools of poetry and flash fiction.

Article continues below…

Flash Nonfiction Writing Courses We Think You'll Love

We've hand-picked these courses to help you flourish as a writer.

Long Story Short: Compressing Life into Meaningful Micro Memoirs

Distill the spirit of your story in fewer than 500 words. Learn to craft compelling short nonfiction, and write and...

Find Out More

30 Super-Short True Stories in 30 Days

Write a flash nonfiction piece every day! Sharpen your skills, build momentum, and leave with a stack of pieces to...

Find Out More

Thirty Tiny Stories In Thirty Days

Discover the exciting possibilities of micro stories, and write a 6- to 250-word story every day for 30 days.

Find Out MoreOr click below to view all courses.

See CoursesArticle continues…

Common Craft Elements of Flash Nonfiction

When reading or writing flash nonfiction, you are likely to come across the following elements and craft decisions:

- Concise Word Choice

- Imagery

- Theme

- Experimentation and Hybridity

Concise Word Choice

With few words to tell a complete story, flash nonfiction writers must push language past its limits. This means allowing words to convey multiplicities, complexities, and nuances, as well as letting images also be metaphors or symbols.

In other words, flash nonfiction often straddles the borders of poetry. When working with the constraints of such a low word count, works of flash, both nonfiction and fiction, sometimes read more like prose poetry.

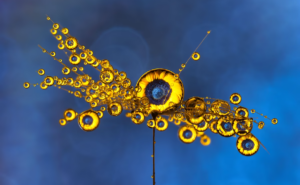

Imagery

Successful literature often operates through striking images. The need for this grows when working within the flash genre, as flash nonfiction writers rely on imagery to convey essential experiences, metaphors, and symbols.

This doesn’t have to be a visual image—imagery as a literary device includes touch, smell, sight, taste, and even things like motion or internal sensation. A resonant work of flash nonfiction will leave the reader with an image or feeling that they digest long after the story ends.

Theme

Of course, all works of literature have a theme. But flash nonfiction must approach its theme in as few words as possible, and thus elevate important ideas so that every aspect of the work points towards them.

This is opposed to works of prose that prioritizes, say, the story’s plot or characters. Flash nonfiction has those elements, of course, but it must waste no words getting to the heart of things: the feelings and energies—thematic elements—that give the story its reason for existing.

Experimentation and Hybridity

Works of flash nonfiction are more likely to experiment with form and structure. Much like in poetry, flash nonfiction’s reliance on concision requires the work to take creative approaches in the telling of true stories. Form and structure offer writers more ways to layer their ideas and structure their thoughts outside of the conventions of standard prose.

A piece of flash nonfiction might also be a hermit crab essay, for example, which borrows its shape from other types of text. Or it might engage with the experimentation of lyric essays or incorporate poetry into the work. Whatever the experiment, successful flash essays discover their own form and language to tell the story that needs telling.

Examples of Flash Nonfiction

Let’s look now at some examples of flash nonfiction to see these principles in action.

“Mary Ruefle Drives Me to the Dentist” by Kelly Luce

Read it here, in Craft Literary.

Mary, I need a root canal. Mary, I need deliverance. Mary, remember when it snowed during dinner last week and you screamed? I would like to be more that way.

This quirky flash nonfiction piece is also an example of speculative nonfiction, in which nonreal, imagined, or speculative elements intertwine with the author’s lived experiences.

It doesn’t actually matter whether or not Kelly Luce was driven to the dentist by the poet Mary Ruefle—though it’s likely that this is just a conversation that happened in Luce’s head. Ruefle’s zany, vivacious presence in the story allows Luce to access the unanswerable questions in her own life, magnifying a mundane car ride into something exploratory.

At times, the prose teeters on the poetic, arriving at epiphany through its wit and concision. Ruefle’s poetry and imagined presence reminds Luce, as well as us readers, to always be moved by beauty.

“Sanguine” by Molly Akin

Our animal hearts once bloody / bloodthirsty now tamed to optimism.

This is a great example of how flash forms push the shape of language to speak in such small spaces. Here, Akin interrogates language itself to understand and convey the painful nature of miscarriage.

This hybrid, braided essay interweaves the author’s own experiences with definitions and etymologies. If anything, I find those definitions to be the most painful, salient moments of the work: it defines the author’s own pain without directly naming it.

You can also see the craft tools of poetry in action: concision, internal line breaks, evolution in form, and a tension propelled by word play.

“Childhood Cranes” by Andrew Bertaina

He’d say, imagine rain falling across the flooded landscape of childhood. Imagine the crane’s soft feathers, gleaming in the autumn air.

You can tell this piece was written by a poet, and not just because it references the poetic craft in the first line. Each image offered in this gorgeous prose cuts closer and closer to the professor’s emotional core, painting a kind of portrait-by-proxy, painted through periphery.

There’s an idea in the craft of poetry called the initiating and generated subject. Essentially, the idea that gets you into the poem is not where the poem ends, nor is it what the poem is really “about.” Successful poetry discovers something and takes a leap.

I feel this is happening here. The professor telling the class about cranes and imagery is just a doorway into what this piece discovers about childhood, nostalgia, memory, change.

“Point of View” by Lina Herman

Read it here, in Craft Literary.

Now I’m thinking I’ll switch to a third-person narrator, I’ll seat them in the window so we can look through the cloudy glass at their matching profiles, their flat noses, their wide foreheads.

This flash nonfiction piece has a kind of metanarrative: there’s the story, and then there’s the author commenting on the craft of the story as it progresses.

It’s an interesting experiment. On the one hand, the author risks interpreting herself for the reader, rather than letting the work be open to interpretation. On the other hand, the metacommentary is a way of inserting the author’s thoughts into the work in a way that feels more genuine. What would a writer do to change the story as it happens in real life? What would it be like to press pause, step outside of one’s self, and reframe the narrative?

That the story’s subject matter would be so intense as to fracture the author’s sense of narrative is enough to make this experiment pay off. We see the story’s lens move, evolve, catch up with the author’s experiences; the pain, distorted, becomes much more deeply felt.

How to Write Flash Nonfiction

Here are some tips on how to write flash nonfiction.

1. Omit Needless Words

It goes without saying that flash nonfiction can’t have wasted words. Really, no good work of writing wastes words. But in flash, the magnitude of concision increases greatly, and words need to have layered, complex meanings to convey a full story in such small space.

It is akin to a circus performer folding themselves into a box: their body is interwoven and nonlinear, as are the words in a flash piece. Here are some tips for omitting needless words:

- Target common filler words.

- Adverbs can often be replaced with better verbs (Does the road “run curvily”, or can the road simply “curve”?).

- Prepositions can sometimes be rerouted or removed (Do you have “a lot of money” or do you “contain riches”? Are you “with child” or “pregnant”?).

- Punctuation, particularly semicolons and em-dashes, can sometimes replace conjunctions and connective words—while texturing your prose. (Note—I originally wrote “making your prose more textured”; turning the adjective “textured” into a verb “texturing” was more efficient.)

- Let images represent themselves.

- It’s tempting to interpret an image for the reader, or to explain an image with a lot of description, metaphor, etc. However, letting images exist on their own without interpreting them for the reader allows the reader to interpret the images themselves, giving the writing room for thematic complexity.

- For example, it’s wordy to say “The countryside felt lonely, with so few people around, and I was aware of how sublime and beautiful nature is.” Besides the fact that the idea is a bit cliché, it chews the reader’s food for them; it conveys no experience.

- A concise way of writing the above idea comes from Kelly Luce’s flash nonfiction piece: “People live out there. Horses stare. Big boulders rest beside barns like ancient pets.”

- Watch out for needless repetitions.

- A free gift is simply a gift; the hot summer sun is merely the summer sun.

For more advice on concision, check out our article on omitting needless words:

https://writers.com/concise-writing

2. Let Structure Lend Its Voice

Another way that flash nonfiction exercises concision is by letting the story’s structure create layers of meaning.

The above flash nonfiction examples showcase how structure is wielded within story. Akin’s “Sanguine” interweaves etymology with personal experience to tell the full story of miscarriage and convey an embodied pain that, otherwise, cannot be easily conveyed. Through a discordant, braided structure, the story comes to resemble, perhaps, the author’s own body after undergoing such trauma.

Conversely, Herman’s “Point of View” incorporates point of view into the story structure itself, creating two stories: the actual event of the piece, and the author’s running commentary as she tries to understand a fundamentally heartbreaking situation. These alternating narratives combine to give the story, again, a sense of discordance, mirroring what the author’s own experience of the event might have been like.

These are ideas that lose their power if they are merely described in the work itself. Akin gains nothing by telling us her miscarriage was difficult; she gains everything by transmitting an embodied experience through her inquiries of language. Herman gains nothing by telling us she didn’t know how to deal with her daughter’s thoughts of death; she gains everything by interweaving the story’s event with her own struggle to understand.

3. Experiment With Perspective

Successful works of flash nonfiction often convey experience through some nonlinear mode of storytelling.

By linear, I mean the convention that a story is one event after the next, told by a single, easily identifiable narrator, who tells us that A led to B led to C.

Narrative is the story we tell ourselves about what happened, and the truth is not always linear. Notice how, in the flash nonfiction examples we’ve shared, the authors’ relationships to time are nonlinear: the narrators look forwards and backwards, sometimes at the same time. They speak from moving cars and classrooms, from dictionaries and park benches.

Think about the best place to tell your story from. From what point of view? With what voice? Exploring what elements of time? These questions can lead to exciting, daring works of micro-memoir that convey more precisely our strange relationships to our lived experiences.

4. Read Flash Nonfiction Regularly

The best way to write successful flash nonfiction is to also read it. The following journals routinely publish great works of creative nonfiction, including flash and micro pieces.

Where to Read (and Publish) Flash Nonfiction

Here are some great literary journals to read flash nonfiction—and submit your own work to when you’re ready.

Write Your Best Flash Nonfiction at Writers.com!

The creative and flash nonfiction courses at Writers.com will help you write your most daring and original stories. Check out our upcoming online creative nonfiction courses, where you’ll receive expert feedback and teaching on every essay you submit.

Thank you for this excellent resource, with such good examples!

More brilliance! I’m guessing I’m not the only Sean Glatch groupie in this community.

You’re right! I’m another Sean Glatch groupie, too.

It’s almost a crime that these craft essays are free, Sean. This one I’m especially grateful for. Thank you so much.

Wonderful explanation of a favourite genre. Thank you