As all storytellers know, setting is a key element of fiction. But what if I told you that the setting is a character of your story?

A setting is not just the ground beneath your characters’ feet. Settings also have personality. A setting reacts to its characters, is transformed through different perspectives, has needs, desires, conflicts, challenges, and is very much a living, sentient thing. This is true whether your story takes place in a forest, a village, a city, or outer space.

A piece of good fiction can make its setting come to life. How does it do that?

Want more craft tips? Be the first to receive our writing advice in your inbox.

Close Study: “Especially Heinous” by Carmen Maria Machado

Read this fabulous novella-length story here, in the archives of The American Reader: https://theamericanreader.com/especially-heinous-272-views-of-law-order-svu/

Warnings for violence and sexual assault.

“Especially Heinous” is an episodic retelling of Law & Order: SVU, complete with speculative strangeness and Machado’s inexhaustible inventiveness. Rather than tell a story in paragraphs and sections, “Especially Heinous” is told in the format of seasons and episode vignettes—the kinds you might read while flipping through cable.

What starts as a crime procedural ends in a genre-bent masterpiece. The reader encounters UFOs, ghost girls with bells for eyes, doppelgängers, and a whole slew of tropes and story structures borrowed from different realms of speculative fiction. Stabler and Benson must contend with their powerlessness to improve a deeply strange, deeply broken world, one which continues to send them horror after horror after horror.

Pay close attention to the structure of this piece. The episodic nature of this story forces Machado into concision, relying on techniques, like irony and juxtaposition, to tell this story both deeply and entertainingly. How can you play with structure in your own fiction writing? What other paradigms might serve your fiction, outside of your typical parts and paragraphs?

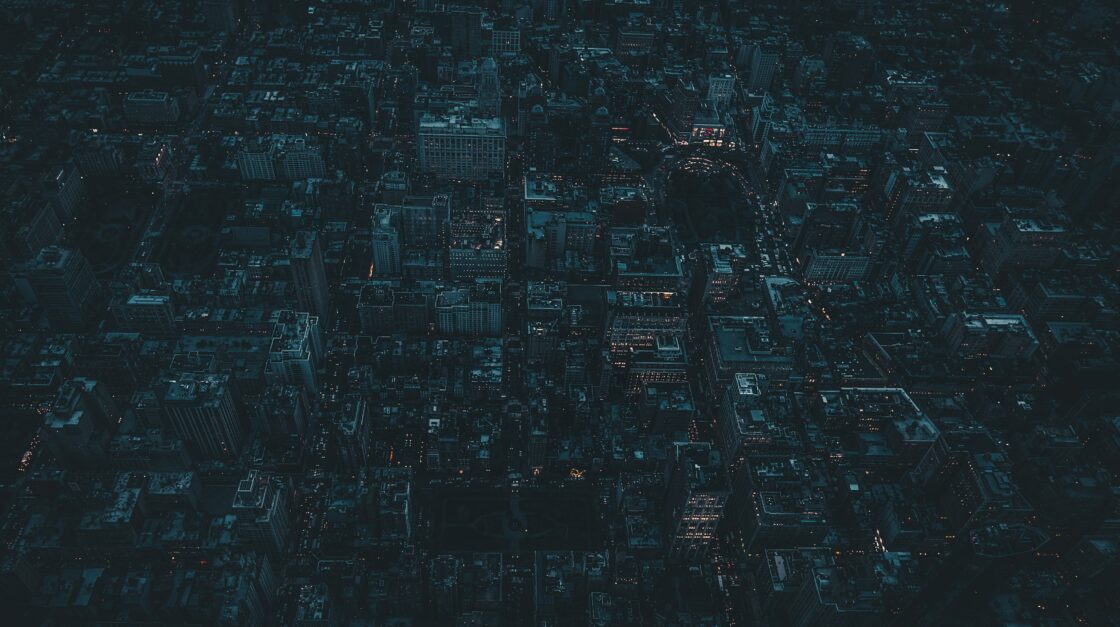

Also pay attention to how the setting comes to life in the story—especially as the setting becomes something we don’t recognize. This isn’t the New York of towering skyscrapers, of Nathan’s Famous and dollar pizza and bodega chopped cheeses. This New York becomes something that breathes, intimidates, imposes itself randomly on its most vulnerable. That’s not so different from the real New York, either, but through metaphor, Machado has turned this setting into something real and dangerous, where everyone should tread a little more carefully.

This is a longer read—technically novella length. Don’t do what I did: I read the entire piece in an hour, and then couldn’t read anything else for a week, because I was so entranced by the writing I couldn’t enjoy anything else.

Craft Perspective: “CENTER OF AN IMAGINARY WORLD: Place in Fiction” by Mandira Pattnaik

Read Pattnaik’s craft essay here: https://www.cleavermagazine.com/center-of-an-imaginary-world-place-in-fiction-a-craft-essay-by-mandira-pattnaik/

In her brief craft essay on setting, Mandira Pattnaik demonstrates something true of all fictional places: both setting and story resemble each other structurally.

In other words, the setting is inextricably interconnected to every other element of the story, down to the personalities of its characters, the ways they handle conflict, and the kinds of plots that the story is capable of handling.

Take the aforementioned story by Carmen Maria Machado, “Especially Heinous.” New York is essential to the story: its horrors and traumas are like clockwork for the city’s underbelly. Benson’s bedroom becomes overridden with the ghosts of girls whose voices were stolen from them, in a city whose density manufactures both awe and terror. There simply wouldn’t be enough ghosts to go around if this story was set in a tiny town, and the characters themselves would be out of place.

Moreover, it’s important that the setting is its own character in the story. Here are some ways New York is described:

- She can feel it. She is suddenly, irrevocably certain that the earth is breathing. She knows that New York is riding the back of a giant monster. She knows this more clearly than she has ever known anything before.

- “It’s the whole city,” Benson says to herself as she drives. She imagines Stabler in the seat next to her. “I’ve been all over. It’s the whole fucking city. The heartbeats. The girls.”

- The city is still hungry. The city is always hungry. But tonight, the heartbeat slows.

- In the beginning, before the city, there was a creature. Genderless, ageless. The city flies on its back. We hear it, all of us, in one way or another. It demands sacrifices. But it can only eat what we give it.

- The city smells it. The city takes a breath.

There are recurring character traits: a hunger, a breath, a heartbeat. The city is described as something uncanny, somewhere between man and monster, demanding and devouring. These traits are closely aligned with episodes where Stabler and Benson discuss the many female victims in the city, implying that the city is a sentient, predatory being. This is necessary to develop the story’s sense of helplessness, of characters contending with forces far outside of their control, only cleaning up the dirt that can never be expunged.

To examine setting in a less personified light, take one of Hemingway’s more well-known short stories: “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place.” The setting, of course, is mentioned in the title, so it’s inherent to the story. But, the point of the story is that we must find a place in this world that seems comfortable and orderly, if only to protect our psyches from the discomfort and disorder of the world and universe. In this instance, that place is a late-night café—the perfect place for this story’s musings and conversations. Can you imagine this story happening at a ballgame, or a children’s science museum?

When you craft your stories, don’t just use settings because they’re convenient. Examine what those settings do for your stories. You don’t just set the stage for the plot, but you set the stage for the story’s symbolism, its themes and metaphors and deeper meanings.

Resources on Setting as Characters

Check out these articles as you craft real, meaningful settings, which themselves become metaphors and symbols of what your characters go through.