If I had to listen to one piece of music forever, it might be “When David Heard,” by English Renaissance composer Thomas Tomkins, as performed by a vocal group called the Gesualdo Six.

Over hundreds of listens, I’ve come to feel that “When David Heard” has a lot to teach us about the power of repetition in our poetry: not just that repetition is powerful, but some oddly deep reasons why it’s powerful.

Below is part of the text Tomkins draws from (2 Samuel 18 from the Hebrew Bible):

O my son Absalom, my son,

my son Absalom!

would God I had died for thee,

O Absalom, my son, my son!

As you can see, the speaker (David) is repeating himself a lot here. This, I think, speaks to the basic quality of our minds.

Our minds are not like a succession of crisp, linear text messages; they’re much more fluid than that. Thoughts gather as ripples of potential, crest, and then recede. Emotions form larger, deeper swells that pulsate, fade, shift, reappear. Powerful, highly charged experiences swamp our minds, like a massive wave swamping a coast; and even that is not static, but it swirls and eddies as it takes its time receding. It might even build and swamp us further, if it happens to come in sets.

David, on hearing that Absalom was slain, was overcome: he was swamped. That is certainly why the original passage contains so much repetition—not to convey new information (which repetition fails to do), but to accurately convey that David was overcome. Grief was hitting David over and over again, like a series of huge waves all caused by the same earthquake. The result, as the passage records, is that David kept repeating himself.

And here is my best attempt to transcribe a section of Tomkins’s choral setting of this same passage, from 1:19 (start of “Oh my son”) to 2:00:

Oh my son my son my son

Oh my son my son

Oh my son oh my son my son my son oh my son my son my son

Oh my son

Oh my son my son my son my son my son my son

Absalom my son Absalom my son Absalom my son

The speech dips in, over, and around itself, moving like a cloud of birds. It is headed in a direction—toward expressing a particular thought—but not only, and not quickly.

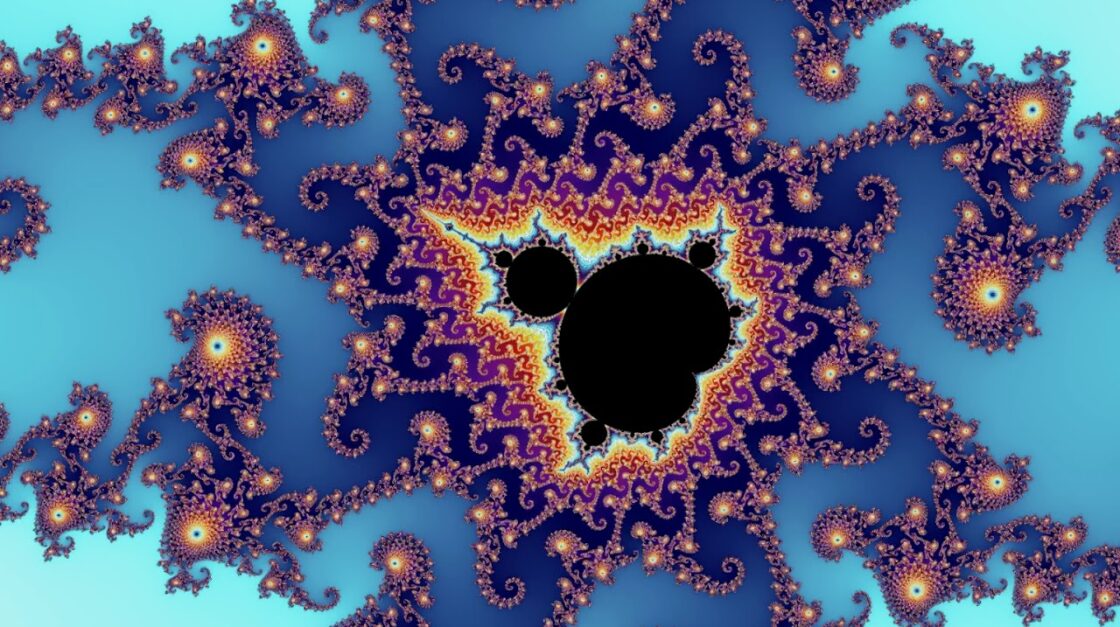

I feel this heightened repetition succeeds in drawing out a transcendent quality. Fractalness, recursion, and repetition are somehow very closely related to sacredness. A few markers of this correspondence are: the Mandelbrot set, an infinitely complicated fractal structure from mathematics that is widely described as feeling profound or sacred; the fractal, kaleidoscopic appearance of DMT entities and the generally hyperbolic geometry of DMT experiences; angels being described as appearing like “a wheel within a wheel” and speaking “like the sound of a multitude”; the tessellated designs of mosque ceilings; “I Am That I Am,” the resounding, recursive name of God in the Hebrew Bible; and how “likes kaleidoscopes” is easy character development shorthand for “is good and holy” in a recent music video.

In the kaleidoscope world, everything resounds, repeats, shifts, transmogrifies, reflects itself. It is not about the efficient transfer of information, but about something inexpressible taking inexpressible pleasure in being itself, reflecting itself, shifting and reconfiguring itself, rubbing up against itself, propagating itself endlessly in forms that are ever unique but ever reflect the whole.

I feel that Tomkins finds, and conveys, this dimension within David’s grief. Tomkins conveys the sacredness of David’s grief: the way mourning the loss of your son and wishing you had died in his stead is more than just a feeling, more than just the heaviest part of a rough day.

He does this by taking the repetition in David’s speech to its extreme, until the text is like “the sound of a multitude”: a kaleidoscope of emotion, moving, soaring, shifting, propagating forward to complete its thought at some point, but in no hurry because of the sheer grace of the propagation. I feel that Tomkins renders David as he might have appeared to angels: as they might have heard David’s lamentations, or relayed them to one another.

As depicted in this text, David was limited, error-prone, not history’s greatest parent (how do you miss the warning signs that your child is plotting to raise an army against you?)—but his love for his son was pure and unconditional. Tomkins lets us feel the sacredness, the blessedness of that love, by showing us its kaleidoscopic version. To adopt monotheistic language, we could say: Tomkins lets us see David as God must have seen him. We see why God must have loved him so much.

This brings us, at last, to the power of repetition in poetry. We can now suggest two answers—one deep, and one very deep—to the following question: Why is it that, for human beings, repeating an element of speech emphasizes it?

Consider that it could quite logically be the other way. When you repeat yourself, you’re not presenting any novel information, so wouldn’t repetition be less powerful? This is exactly true if you happen to be talking to computers, which is why “Don’t Repeat Yourself” (“DRY”) is one of the closest existing things to universally good advice for programmers. Similarly, for jokes, “I’ve heard that one already” is not a good thing. So why, and when, does repetition work for poetry?

The deep answer is that repetition works because it reflects, and works when it reflects, how our minds function. As we discussed above, our minds are fluid and resounding: strong emotions, in particular, arise in mind not once but again and again, and our speech reflects this: “My son, my son, my son…” So repetition is powerful in poetry because it resembles—and thereby invokes—powerful emotion: invokes how powerful emotion plays out in our minds, rebounding and shifting and repeating like big swells on the ocean, or a shout at the mouth of a large cave.

And the very deep answer is that repetition evokes the fractal, recursive, kaleidoscopic nature of sacredness itself. Even viewed in purely physical terms, reality has an “as above, so below” structure: look at anything, and you see the same basic patterning that defines everything. We can “see a World in a Grain of Sand,” as Blake said, and repetition manifests this by structuring our poetry not linearly, but in terms of a net of relationships between seemingly disparate things, each of which shares an underlying sameness.

So how may we use repetition to these effects in our poetry, and when does it work? (“Not always,” to get that out of the way.) Read on for some thoughts and exercises.

Playing with Repetition: Exercises and Suggestions

In this section, we’ll look at lots of snippets that do repetition well, and try to tease out some themes.

From the Gettysburg Address:

of the people, by the people, for the people.

The organizing principle of the United States is supposed to be the people, and Lincoln expresses this core aspiration as well as anyone ever has. Through repetition, he emphasizes the people as the constant around which all elements of the nation’s government are constructed. The prepositions, meanwhile, change to capture each role the people fill, like hats coming on and off a Mount Rushmore head.

From the Dream speech:

Free at last. Free at last. Thank God Almighty, I’m free at last.

This is the first type of repetition I mentioned above: being repeatedly buffeted by overwhelming emotion, in this case joy. The musicality of the “rule of thirds” does a lot of work here (neither two nor four repetitions would do as well) as does the “A A B A” structure—pattern, pattern, departure, pattern—which binds the utterance together into a coherent whole.

A first theme, visible in these two examples, is to repeat what matters. In other words, repeat the primary element that keeps reappearing in mind, or the common core—the shared nature—of multiple seemingly disparate elements. This common core in the first example is “the people”; what keeps reappearing in mind in the second example is “free at last.”

Let’s reluctantly butcher these two phrases to show them still using repetition, but emphasizing the wrong thing: “Government of, government by, and government for the people.” You’re impeached! “Free at last. Thank God, thank God, thank God.” That was oddly flat!

A second theme is “transmogrification.” (This is my own term, not a necessary one.) Before we define it, let’s look at some examples. From The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock:

dying with a dying fall.

From Tennyson’s In Memoriam:

So runs my dream: but what am I?

An infant crying in the night:

An infant crying for the light:

And with no language but a cry.

And here are a few lighter examples, from rap. From Eminem:

One day I was walking by

with a Walkman on

when I caught a guy

From Doja Cat:

Said if these are clothes, m_________r, what are those?

You look like a butter face,

butter body,

butter toes

From Chance the Rapper:

I hope you never get off Fridays,

and you work at a Friday’s

that’s always busy on Fridays

In each of these cases, what’s repeated is also being shifted, morphed, transmogrified. The meaning, the sense of the word, changes with each repetition, while the repetition preserves an underlying unity. It’s a miniature linguistic version of how, for example, the Mandelbrot set continually shows a new edge of the same whole.

To me, this approach to repetition has resulted in some of the most delightful and memorable passages in all language. It’s not necessarily easy to pull off, though, because you need to be attuned to the many meanings a word can have. This requires, for example, employing both “crying” as a verb and “cry” as a noun; or “dying” as a verb and “dying” as an adjective, paired beautifully with “fall” as a noun; or hearing the felicity between “walkin’ by” and “Walkman on”; or thinking about both Fridays (the day) and Friday’s (the restaurant). It takes a lot of cleverness.

So, give repetition a try. If you can write the wheel within the wheel—resounding, unhurried, recursive, shifting, kaleidoscoping, morphing, transmogrifying—you will write the voice of the angels; or, if you like, you will write the true, not particularly linear, voice of the human mind.

As a first exercise, listen to your mind and see what repeats itself: see what is insistent. Write a poem about that. Here’s what came out:

My dog is getting older.

She has stiffness in her hips, allergic patches on her shoulder.

She is getting older.

Her eyes are steady, loving when I hold her.

They are as they used to be.

But I see that she is getting older.

My dog is getting old.

Really not bad for a poem dictated line by line into my phone and then fiddled with in this article. What gives it any life at all is certainly the repetition of what matters (“my dog is getting older”), as well as the transmogrification from “older” (comparative, in transit, still some wiggle room left) to “old” (absolute, final, arresting, deathlike). For a much better poem with some structural similarities, see Langston Hughes, “Poem.”

As a second exercise in transmogrification, think of a word that is a noun, a verb, and an adjective, and play with that. Here’s something tossed off:

I’ll set my mind

My mind is set

My mindset

Definitely not great poetry, but one can see how multiplicities of meaning could start to reverberate here—setting aside a general queasiness about writing a poem containing the word “mindset,” which would definitely need to be addressed.

For much more on repetition, please see our article on the topic, and I’d love to read anything you come up with as you play with it. Thank you for reading!

I teach a whole online class session on the effective use of repetition in poetry and have some great examples. Probably my favorite is Wallace Stevens, “Domination of Black”.

https://allpoetry.com/Domination-Of-Black

So many poets aren’t aware how powerful and impactful the careful, conscious use of repetition (especially anaphora) can be. T.S. Eliot and Walt Whitman were very skilled with repetition also.

And I’m teaching a Robert Frost poetry course online soon — during which we’ll spend considerable time discussing all the misinterpretations of “and miles to go before I sleep!”

Tracy Marks

I love this essay, Frederick. Positively love the way you weave together the repetition in musical composition with repetition in poetic composition. AND, I do lovingly embrace how you characterize a kaleidoscopic world when you write:

“In the kaleidoscope world, everything resounds, repeats, shifts, transmogrifies, reflects itself. It is not about the efficient transfer of information, but about something inexpressible taking inexpressible pleasure in being itself, reflecting itself, shifting and reconfiguring itself, rubbing up against itself, propagating itself endlessly in forms that are ever unique but ever reflect the whole.”

Thank you, Karen! 🙂

This is a brilliant article. Thank you so much for describing the indescribable so well.

Thank you so much, Carolyn!

I found your reference to “When David Heard” striking, and not just because it’s an excellent example of repetition done well (particularly in this performance). It also brings to mind the insufferable monotony that afflicts too much of the contemporary “praise and worship” music played in today’s churches. There’s a reason many jokingly call it “7-11 music—” the same seven words repeated 11 times in a row. This article should be required reading for church music directors everywhere.

Thank you, Joe! 🙂