Speculative nonfiction is an emerging genre of literature that empowers writers to incorporate imagination, wondering, and non-shared realities into works of creative nonfiction. By writing into the realm of possibility, speculative nonfiction writers can make interesting discoveries, or explore truths that might have otherwise been hidden by strict adherence to matters of settled fact.

This is not to suggest that speculative nonfiction is a means of lying or fabricating: the speculative essayist makes it clear when the essay is veering into speculation. Rather, this genre unlocks a new means of truth seeking, generated from the writer’s imagination, unconscious mind, and lateral thinking.

This article explores the exciting work being done in the world of speculative nonfiction, with examples, prompts, and doorways into developing a deeper understanding of the truth.

Writing Speculative Nonfiction: Contents

What is Speculative Nonfiction? Defining the Genre

Like many literary genres, speculative nonfiction is easier described than defined. Think of it more as a mode of literary production, rather than an all-encompassing type of writing: it is both a style of nonfiction writing and a tool for nonfiction writers to use.

At its most broad, speculative nonfiction is the incorporation of imagined or non-shared realities to explore the truth of real experiences.

Speculative nonfiction is any piece of nonfiction writing that uses speculation, wondering, or invention as tools for uncovering different truths.

Less abstractly, speculative nonfiction is any piece of nonfiction writing that uses speculation, wondering, or invention as tools for uncovering different truths. The speculative nonfiction writer might ponder or perhaps their way into information they don’t know, or else use forms of altered consciousness, including dreams, as doorways into understanding.

Article continues below…

Speculative Nonfiction Writing Courses We Think You'll Love

We've hand-picked these courses to help you flourish as a writer.

Speculative Nonfiction: Writing Beyond the Known

Explore the emerging field of speculative nonfiction—nonfiction on the edges of what is known—and discover new truths as you write...

Find Out MoreOr click below to view all courses.

See CoursesArticle continues…

What is Speculation?

Speculation is any form of wonder or inquiry towards what cannot be truly known.

This isn’t to say the speculative writer makes something up and assumes it to be true. Rather, speculation is a means of generating insight or understanding through inference and intuition.

Speculation is a means of generating insight or understanding through inference and intuition.

The speculating writer might:

- Consider different possible outcomes than what actually happened.

- Generate insight from dreams, hallucinations, or other forms of non-shared reality.

- Wonder at events of the past that are not documented or possible to research.

- Draw upon other forms of storytelling, such as folklore or mythology, to represent different forms of truth or truth-seeking.

- Fill in the gaps of memories that only partially exist or are notably imperfect in the writer’s mind.

The key idea here is that speculation acknowledges its own limitations. It does not try to present ideas as facts, or argue that this definitely happened, but rather uses imagination as a means of storytelling and inquiry, allowing the writer to use their intuition as a means of discovery.

Does Speculative Nonfiction Give Me Permission to Lie?

Absolutely not. In fact, good speculation requires the writer to make their speculating clear.

It is always obvious in a work of speculative nonfiction when the writer is veering from the facts of shared reality.

It is always obvious in a work of speculative nonfiction when the writer is veering from the facts of shared reality. Some common words and phrases you might see when entering the realm of the speculative are:

- Perhaps

- What if

- Maybe

- I wonder

- I imagine

- It is likely that

- It would follow that

And any synonyms or similar ideas to the ones above. So the reader will always know when the writer is speculating. Otherwise, the writer might present their inquiries as truths, which would be both dishonest and dangerous, depending on what the writer speculates about.

Besides, there is a lot of power to wondering. Readers of speculative nonfiction appreciate the genre’s ability to reveal the writer’s own mind and relationship to the world.

What Speculative Nonfiction Isn’t

As writers explore new avenues of storytelling, the lines between fiction and nonfiction seem to get blurrier. But, to be clear, speculative nonfiction is not:

- Autobiographical fiction. In this genre, the author acknowledges both that the story is informed by their lived experiences, and that their experiences have been modified (without the use of speculative language) to present a different or richer story.

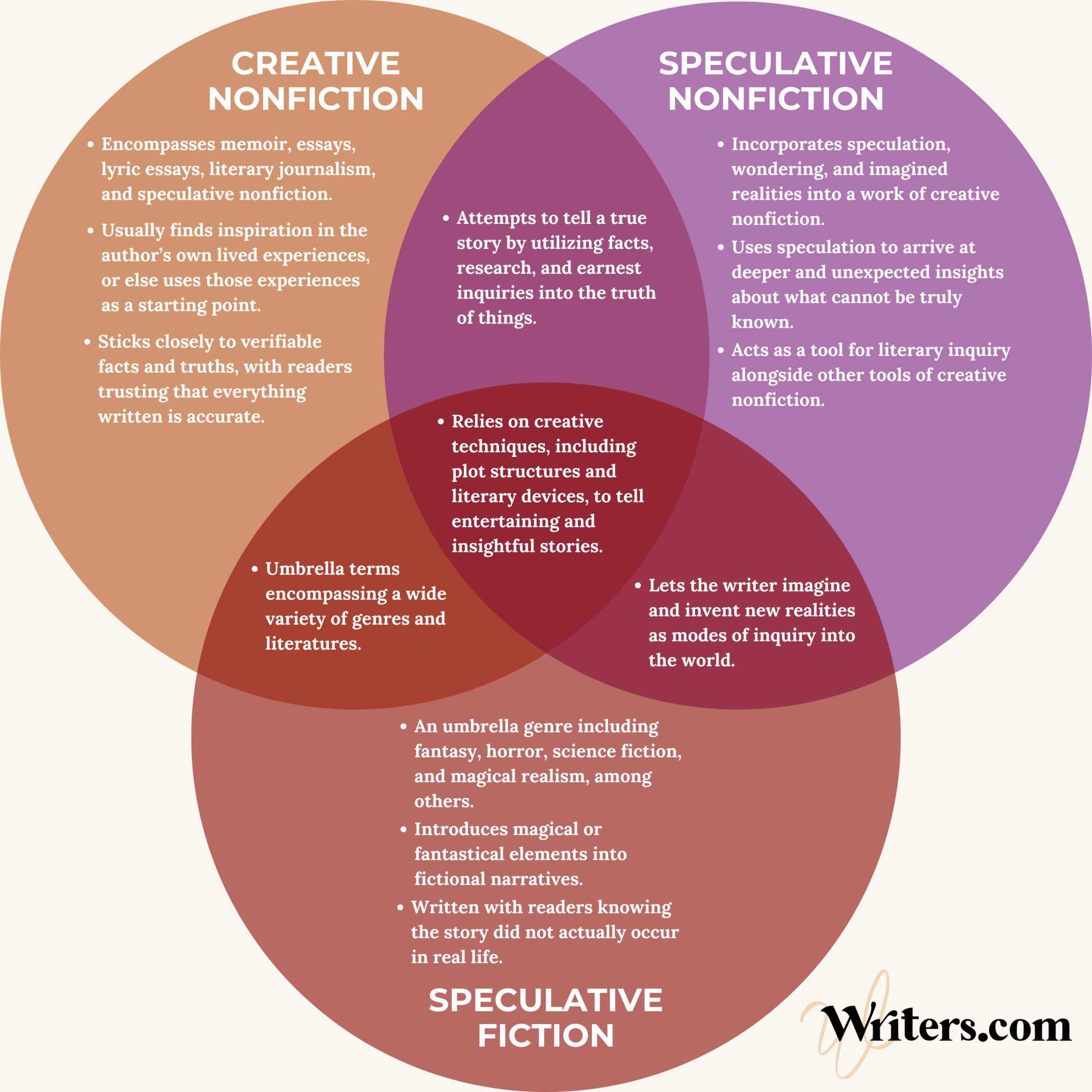

- The use of magical, futurist, or non-realistic elements in fictional narratives. That would be speculative fiction, a genre that encompasses fantasy, horror, science fiction, and magical realism.

- Historical fiction. Historical fiction might also use speculation to tell aspects of the story that cannot be researched, but historical fiction is preoccupied with the broader aspects of history, including the politics, culture, and experiences of a certain time period. Speculative nonfiction, by contrast, is still very much rooted in the writer’s own lived experiences and personal histories.

- Any genre of fiction, really. Fiction requires the reader to suspend their disbelief and treat the story as something that did or could have happened, even though the reader and writer both know the story is invented. Speculative nonfiction is still nonfiction, so it explores things as they truly occurred.

Learn more about the contours of fiction vs nonfiction here:

https://writers.com/fiction-vs-nonfiction

Speculative Nonfiction Examples

The concept of “speculative nonfiction” is a very 21st century invention. It’s not that writers before now haven’t been speculating, because they have—but the idea that speculation deserves its own genre is new and promises a lot of literary innovation.

As such, the following examples are contemporary and showcase a lot of the new exciting work being done in this burgeoning style of creative nonfiction.

“‘Time’ is the Most Common Noun in the English Language” by Daniel Olivieri

Read it here, in Speculative Nonfiction.

“Just as fitting as the inventor of the watch being a locksmith is that the mythological Fates were weavers. The shortest threads sewing shops sell are 1800 feet long, the length of five football fields. Can you imagine how unwieldy it would be to handle all that thread if we didn’t have spools to wrap it around? The months, weeks, and years are the spools we wrap our time around. Without them, time would be as unmanageable as a tangled clump of thread.”

This quirky essay was published in Speculative Nonfiction, a literary journal dedicated to this genre. I encourage you to read their archives for more inspiration—and maybe even submit to them yourself!

One benefit of speculation is its ability to suspend time: we freeze from the narrative to explore the past, the future, or even present-moment possibilities. Which is why Olivieri’s essay is all the more enjoyable: it’s about time, our relationship to it, and how societies and civilizations have grappled with this fluid and nebulous concept.

Olivieri invites the reader into his speculations and suspends time for us in the process. What does it mean that the Egyptians had a 5-day month, or the French tried to implement a 10-day week? How would our relationship to time change if we measured it differently? These questions both demand answers and refuse them, which make them all the more exciting.

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado

Read this review of the memoir at Ploughshares.

I love Carmen Maria Machado’s fiction, but her nonfiction is just as daring and vibrant. In the Dream House is a speculative memoir about Machado’s experiences of domestic violence with a former partner, who is only named “the woman in the dream house.” The memoir is written in the second-person point of view, and often incorporates different narrative and stylistic experiments.

Machado is a speculative fiction writer, so it only makes sense that she would borrow tools from the genre to write speculative nonfiction. In the memoir, metaphor acts as a liminal realm between tangible reality and Machado’s own experiences—they are more than just elegant comparisons, they are feelings so raw and intense as to actually have happened. Here’s a brief excerpt:

Dream House as Double Cross

This, maybe, was the worst part: the whole world was out to kill you both. Your bodies have always been abject. You were dropped from the boat of the world, climbed onto a piece of driftwood together, and after a perfunctory period of pleasure and safety, she tried to drown you. And so you aren’t just mad, or heartbroken: you grieve from the betrayal.

The result is a memoir that does more than just communicate a tangible lived experience—it’s a searing inquiry into the nature and history of domestic abuse in lesbian communities, aided all the more by the incorporation of speculated, yet true, realities.

“Mary Ruefle Drives Me to the Dentist” by Kelly Luce

Read it here, in Craft Literary.

“Mary, what do you think? Mary thinks words are stones. Mary likes when things intersect. One time, Mary and a friend were here and the day was so nice, too perfect to stay in and work, so they got in the car and got lost.”

This funny, charming, imaginative flash essay showcases the blurred lines and liminal spaces of speculative nonfiction. In it, Luce ends up writing an ode to the poet Mary Ruefle (and her quirkiness) while navigating her own life’s struggles—and the route to the dentist.

Whether or not Mary Ruefle ever drove Kelly Luce to the dentist is less important than what is generated in this essay. The wisdom of Ruefle’s poetry interrupts each paragraph like an epiphany. The essay almost becomes a lesson in how to live your life, but without the preaching qualities of didacticism.

Through this conversation, Luce speculates through her own problems and decisions. “Mary, should we go back? Mary, should I leave my husband? Mary, give me answers.” While poets and poetry often resist direct, uncomplicated answers, Ruefle shows Luce a different way of living, one in which we scream when it snows during dinner, in which we are constantly surprised by beauty.

Bruja by Wendy C. Ortiz

Here’s an interview Ortiz did about Bruja with The Rumpus.

Bruja is what Ortiz calls a “dreamoir”—a memoir told entirely through dreams. It is such an interesting project. The writing operates through vivid, detached descriptions of Ortiz’s dreams, with no intervention to explain who the characters of these dreams are or how they relate to Ortiz in real life.

Nonetheless, the reader, over time, picks up on who in these dreams are friends, family, lovers, or strangers based on how they operate in Ortiz’s mind. This is, fundamentally, a project of selfhood through a charting of the unconscious mind, and Ortiz asks us to construct her through the ways her dreams showcase her psyche.

Here’s an excerpt, rich in the symbolism and strangeness of dreams:

AUGUST

I drove a black truck to visit Olympia. I had cats with me. I parked outside the garage of the first place I ever mud-wrestled and when I opened the door of the truck, the cats kind of spilled out. The cats weren’t mine and I panicked. After unloading some containers of spoiled food (pasta, fruit, lentils), a bunch of cats caroused all around my feet. I was overwhelmed trying to figure out which one was the one I was missing. Some had little tiny slips of paper on the napes of their necks, where you hold them when you want them to submit to the power of the mother cat. I saw numbers and some lettering on them, but none of it told me which cat was which. They all looked exactly alike.

When I found the right one, I got him into the truck cab while all the others continued brushing against my feet and calves.

While not “speculative” in the sense of perhaps and what if, Bruja accomplishes the project of speculation by inviting the reader into the singular consciousness that is a person’s dreamworld, further complicating what is fact and what is fiction, as a very real writer constructs herself through stories that (technically) never occurred.

Are Invented Truths Still True?

Speculative nonfiction remains nonfiction for its ability to ponder into truth. That said, the speculating writer is drawing upon hypotheticals, musings, and altered states of consciousness to inform their work, and those things are inherently singular to the individual, and thus only accessible through the writing itself.

This begs the question: are invented truths still true? In other words, can we trust that the writer is telling the truth? Can we trust the truths accessed through speculation?

First, it’s important to break down the difference between absolute truth versus relative truth.

- Relative truth: The idea that there is truth to be found in our singular experiences, and that our perceptions, though flawed, still contain truths about our feelings and lived realities. Relative truths are not universal, and can contradict one another. The lines, of course, get blurry, because someone can present a lie as being a relative truth.

- Absolute truth: The idea that there exists a truth that is universal and incontrovertible, yet inaccessible to us. Absolute truth is asymptotic, something to strive for though it can never be achieved, as the workings of human biases and our own perceptual limitations prevent us from fully accessing the truth of things.

If I say the sky is blue, for example, that might seem like an absolute truth—until we deconstruct it. The sky appears blue because of the refraction of light against nitrogen; it appears blue because of how that refracted light interacts with the cones in my eye, miles and miles below; it appears blue only because the sky is also cloudless and the sun is shining. The sky is not blue for everyone who can perceive it, and so this truth is only relative to my own point of view.

I go a little more in-depth in these concepts at this essay on the search for truth.

All types of creative writing, speculative nonfiction included, rely on the mechanisms of relative truth to search for something more absolute.

All types of creative writing, speculative nonfiction included, rely on the mechanisms of relative truth to search for something more absolute. So it is less about fabrication for the sake of fabrication, and more about having a set of inquiries that allow us to access truth in different ways.

In Bruja, for example, I have no way of knowing whether Ortiz is accurately reporting the events of her dreams. And, although she kept a rigorous dream journal, it’s very possible that the dreams as they occurred were still distorted simply in the act of transcribing them: the author made sense of what was inherently nonsensical, and thus assigned order to a disordered narrative.

But Bruja is a project of understanding selfhood through dreams, and that understanding occurs both through the symbolism of the dreamworld and through the act of transcribing those dreams to the real world. Neither method of inquiry contains the self-asserting truth of the scientific process, yet the reader comes to trust these dreams as intuitions into Ortiz’s life.

Another good example is the essay “What He Took” by Kelly Grey Carlisle, published in The Rumpus. Here’s an excerpt riddled with speculation:

Sometimes I imagine my mother in the months before her death. I imagine, for instance, that it was raining when she finally went to the clinic. This is implausible, of course, because she probably went in May or June, months when it doesn’t rain in L.A. But I like the rain, and I like to think she did too, and so I make it rain as she waited at the bus stop. It was 1976 and so I imagine Chevettes and Galaxies driving by on the busy street in front of her, their tires kicking up a fine mist. Her jeans were probably too long for her, as mine are. Their hems were frayed and wet. Perhaps she leaned back against the smoky translucent plastic of the shelter, then touched her stomach. Just a faint, quick touch, as if she were checking to make sure her top button was fastened, but it wasn’t that. She hadn’t fastened that button for weeks.

What do we gain from this paragraph? It stays strictly in the realm of the perhaps, imagining a truth that cannot be known. What could possibly be true about these sentences that rely on invention to exist?

What we gain is understanding the writer’s own relationship to her mother, her desire to be similar to her in taste and fashion, and the resonance of imagining a person’s life soon before their unwitting death—how more alive it makes them seem. So the truth accessed here isn’t one of narrative, but of understanding the author’s own self, and of imagining a world whose likelihood is less relevant than its emotional honesty.

The point is that speculation serves a purpose in revealing—first to ourselves, and then to our readers—what we know, feel, and think.

The point is that speculation serves a purpose in revealing—first to ourselves, and then to our readers—what we know, feel, and think. This mode of inquiry offers writers freer access to their own intuitions. So long as we frame our speculation as just that—a set of perhapses, imaginings, and wonderings—we allow our invented truths to announce themselves as inventions, and our intuitions to discover something in the process.

Prompts for Writing Speculative Nonfiction

Want to try your hand at writing speculative nonfiction? Here are some doorways into writing this exciting genre.

- Write an essay about a dream that you have had but do not understand. What was your subconscious trying to tell you? What images, symbols, or words stand out to you? Explore the dream world and let yourself be open to unexpected insight.

- What is a memory you have where the details are fragmented or incomplete? Write an essay that speculates about those absences and tries to intuit its way into a more complete story.

- What is an aspect of your personal or family history you have questions about, but cannot find any answers on? Orbit those answers by speculating through what you know about the people and places that populate this story, then let the essay’s centripetal force draw you into insight.

- Write an essay in which your feelings are made tangible through metaphor.

- What is an event, either in your own life or in history, that you wish had a different outcome? Write an essay that hews closely to the facts of that event, but speculates about how the present moment would be different had that event had a different outcome.

- Write an essay in the form of a conversation between you and an important figure in your life—a conversation that has never actually occurred.

Check out Writing Beyond the Known with Joanna Penn Cooper

Want to learn more about how to write speculative nonfiction? Check out our on-demand self-guided course, which you can enroll in at any time:

More Creative Nonfiction Resources

If you’re looking to further hone your creative nonfiction writing, here are some additional resources.

- How to write a personal narrative essay

- Writing about real people

- How to write a memoir

- Writing the lyric essay

- Types of nonfiction

Explore Speculative Nonfiction at Writers.com

Want to hone your skills in speculative nonfiction? The courses at Writers.com can help! Check out our upcoming creative nonfiction courses, where you will receive expert feedback on every piece of writing you submit.

Very interesting article. I will definitely take your upcoming course on speculative fiction. I expect this genre will be most beneficial to my memoir writings.