This craft essay was first featured in the Writers.com Poets newsletter. Subscribe below!

Poem: “Everything All at Once” By Oliver Baez Bendorf

right now,

someone is having sex and someone

is dying and someone is trying to find

a lid so they can, before bed, put away

the soup and someone is dreaming

of that made meadow and someone

is gazing through a hospital window

to a faraway peak

and someone can’t decide what

to watch so they remain

on the menu screen for company

and someone wants to call but

can’t and someone wants to answer

but won’t and someone is studying

to become a moth scientist and someone

is dizzy and doesn’t know why

and someone is, after work, practicing

the vocal techniques of opera

and someone receives

a phone call saying listen it’s my

neighbor I told you about the singing one can you

hear it and someone

is clutching the heavy still warm hand

of a lover and someone is digging

a hole and someone is waxing

their back and someone

is remembering a poem permitting

bits and pieces to return

and someone

would do almost anything to forget

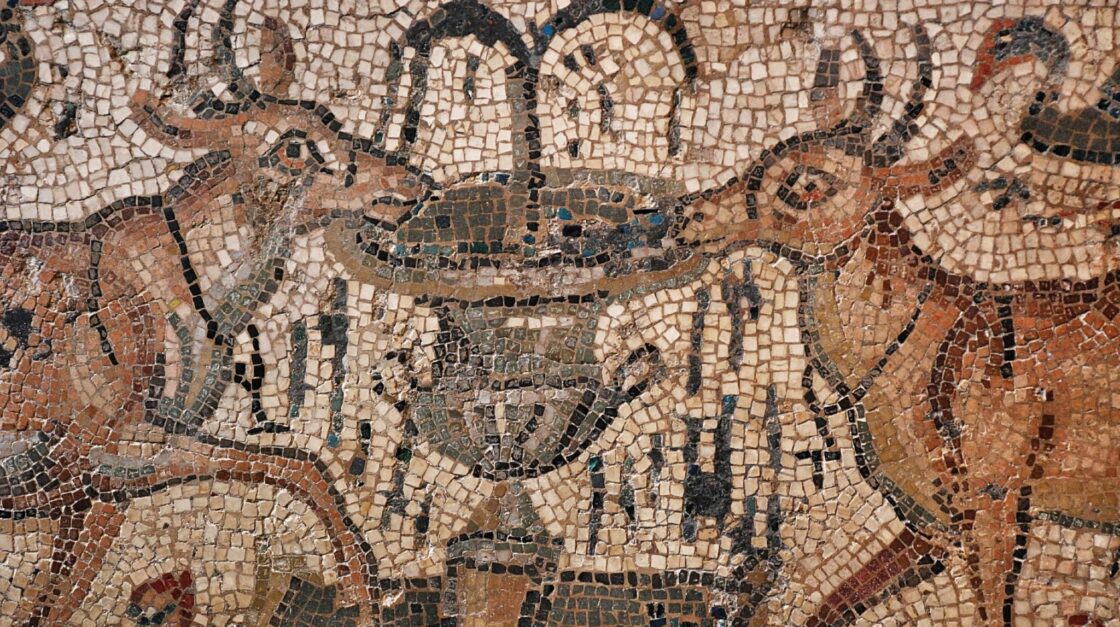

This lonely, dizzying poem manages to make me feel a lot of the world’s pain all at once—but, weirdly enough, not in a way that’s painful. I used this poem in a workshop I run where the theme was “poem as mosaic”: what would it mean for a poem to be composed of tiles or fragments that become a composite picture?

In the case of this poem, the picture is the world itself. There are a few craft elements I want to point your eye towards, including:

- The poem’s line and stanza breaks,

- Strategic placement of the word “someone”, and

- The lack of an easily identifiable speaker.

The poem’s lineation feel almost vertiginous. Line breaks happen almost randomly, often cleaving an action in two, but doing so haphazardly. Why, for example, is “someone” separated from “is dying”—while a different “someone is dreaming / of that made meadow”?

For most of these anonymous subjects, their selves and actions encounter some form of discontinuity. That discontinuity is heightened by the poem’s lack of punctuation: enjambed line after enjambed line lets disjointed experience flow.

And, that discontinuity feels even more amplified at the stanza breaks. Here’s that first break:

and someone can’t decide what

to watch so they remain

on the menu screen for company

That break creates a very real chasm between “someone” and the menu screen, which is already a rather lonely form of company. And then the second stanza break:

and someone receives

a phone call saying listen it’s my

neighbor I told you about the singing one can you

hear it

What is that break, here? A skip in the phone’s connection? The distance between two callers? These are such lonely leaps that we traverse on the poem’s journey. The lines and stanzas imbue the poem with its overall sense of fragmentation and discordance.

Which brings me to those fragmented and discordant subjects: the someones. The anonymity is, of course, intentional: the poem is interested in the totality of human experience at a single point of time. But there’s a tension in this poem’s craft. The form of it, its lineation, is lonesome, but “someone” is everywhere.

And I mean that quite literally. Notice how “someone” roams the page, the line. Sometimes at the line’s start, sometimes the middle, sometimes the end. “Someone” is everywhere—is “Everything All at Once.”

In other words, the poem’s form makes it so that “someone” fills the poem’s geography. The lineation is both lonesome and connective; it cleaves and it yokes.

If that weren’t enough presence and absence for you, the speaker itself is hard to identify. They’re an observant voice, they document, but where are they in this poem? Are they one of the “someones”? Are they the someone trying to forget?

I don’t have the answer there, but this gap between speaker and identity adds to the poem’s enduring tension, that of our innate loneliness, or innate connectedness. Really, there are thousands of someones at any given time gazing through hospital windows and waxing their backs. Our shared humanity is a strange one. And also beautiful.

I wouldn’t say this pieces breaks the “rules of poetry“, per se, but it certainly stands out. It’s rare that I see poems written from an anonymous vantage point, and rarer, still, that contemporary poetry tries to encapsulate everything into itself. That the poem is able to do this and convey the feeling of being human through it is no small feat.

Craft Perspective: “Richard Siken on the Most Fundamental Poetic Device There Is”

Richard Siken is the poet I credit most for getting me into poetry. Naturally, I’m a fan of his insights on craft. He recently published a collection of prose poems, I Do Know Some Things, which documents his grasp at memory and selfhood after a serious stroke.

I don’t have much to add to this interview, because Siken says things perfectly. A poem’s possibilities rest in its pursuit of better language; we need it to say what plain language so often can’t. Nonetheless, I’ll quote this response from him:

The line break is one of the most fundamental poetic devices there is. When you break a line, you make a friction between the line and the sentence. The line goes one way, the sentence goes another. The line break produces simultaneous meanings. You get a chord of meanings instead of a single note. After my stroke, I lost my sense of line. And things were so broken, I didn’t want the disjunction of a line break. I was striving to finish my sentences. I was going to measure my progress by my ability to make a paragraph, to convey a single thought completely.

This meant that every poem was going to be a block of text, a single paragraph. The poems were all going to look the same. I lost a lot when I lost the line, so I had to make use of other swerves and complications. I varied my modes—lyric, narrative, meditative, rhetorical—and I varied my tone. I varied the speed, the direction of address, the emotional distance. I tried to keep the language thick and interesting.

Every poet has their own relationship to language, so don’t try to borrow Siken’s mind as your own. But the possibilities he names here showcase so much of what draws me to poetry. In Baez’s poem, for example, I see what Siken is talking about: the friction between line and (ongoing) sentence; the chords of meaning, the disjunctions.

And, every poet will break the line in their own way. A line exists as an independent entity, a miniature collection of standalone words, placed in conversation with other lines that amplify and contradict and alchemize with each other. In your own work, especially in revision, ask yourself what your lines can do to serve your poem’s intent?

For more on the line break, read our article here: