Joan Didion and New Journalism

Good writing doesn’t construct, deconstruct, or reconstruct life, it simply explores it.

Recently I’ve gotten more into creative nonfiction, and the transition has been a refreshing change of literary pace for me. One work I was long overdue on reading was Joan Didion’s The White Album (1979), an essay collection published in the era of what’s called New Journalism.

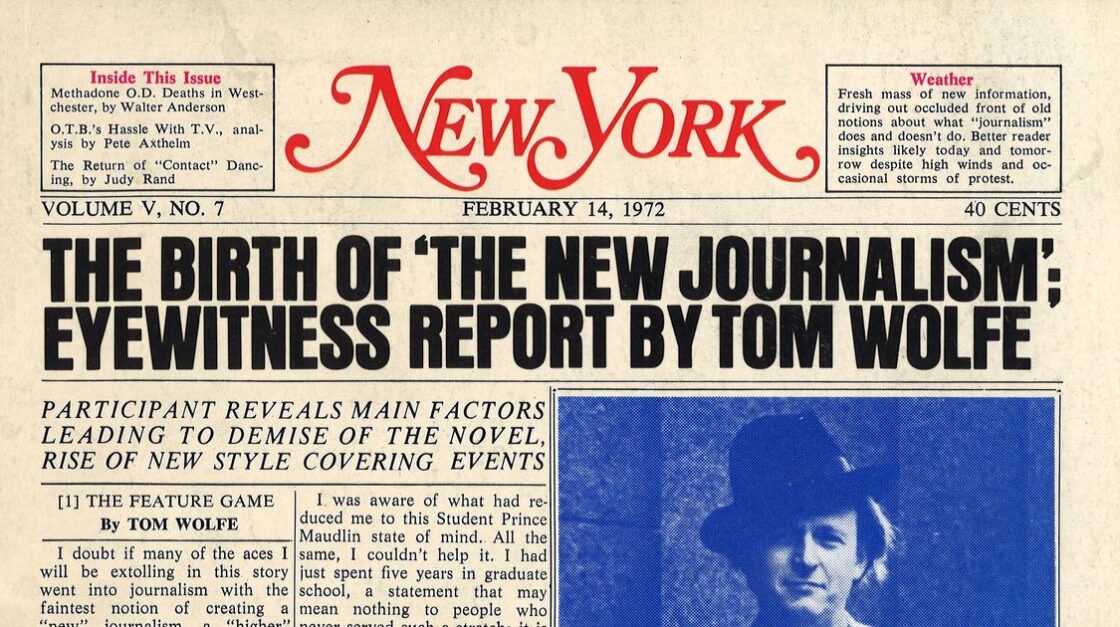

New Journalism was popular in the 1960s and 70s. It’s a style of literary reportage in which journalism is mixed with the techniques of fiction and nonfiction writing. Rather than describing the world from a remote, third person, apolitical perspective, the writer involves themselves in the narrative of the journalism they’re reporting, and the “I” becomes a crucial lens, an access point into new corners of the world.

Conceptually, I love New Journalism. There’s no such thing as an unbiased opinion, and rather than scrubbing out one’s sense of self to create a more balanced, neutral work of prose, New Journalism’s emphasis on the individual allows the reader to engage with the world through different, more pronounced perspectives. It opens the door to more disagreement, but also to more understanding. Besides, there’s nothing wrong with disagreement, and I find the presence of “I” in a work of journalism to be more engaging, both narratively and ideologically.

In practice, I think good journalism is difficult, and good New Journalism even harder. Some of Didion’s essays I deeply admired; others left me cold.

The White Album begins with its eponymous essay “The White Album.” This essay is spectacular. You can read it here. On the surface, Didion explores the overlap of the 1960s and 70s, including events in popular culture and the news. The Doors, The Ferguson Brothers, student protests, Janis Joplin, and The Black Panthers are just some of the prominent signifiers of this time. But the essay leads with its organizing principle, as well as one of Didion’s best quotes: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

Really, what Didion explores in this essay is her inability to apply narrative sense to the chaos of her time. As a writer, she went through the motions of narrative—of A led to B led to C—but could not convince herself of those stories. I understood this feeling instantly. A story can give anything that patina of fact, as though, just because something makes narrative sense, it’s true at a literal level. (Such is the power and danger of storytelling.)

To agree or disagree with Didion’s observation involves a certain engagement with Nihilism. After all, Didion is saying she could not find or apply meaning to the events of her time: things occurred without causality. She nonetheless provides her account of the culture in the years surrounding 1970, and with this Nihilism foregrounding her stories, I, as a reader, strived to make sense of The Doors or the Ferguson Brother murders. But, like Didion, I could not be convinced of the stories, important though they are. The essay culminates in Didion’s diagnosis with Multiple Sclerosis, an autoimmune disease that attacks the brain and spinal cord, disrupting the movement of nerve signals. It’s almost like Didion’s lack of narrative sense mirrors that interruption of nervous movement: it was, as Didion writes, “another story without a narrative.”

This essay might be too dark for some, but I loved it. Didion put into words certain feelings I’ve known but not named, an experience I always find refreshing. Even though the feeling here is Nihilism, I felt its opposite: a relief at having made sense of the senseless, even if senselessness is the subject. Here, I think New Journalism works its magic. My perspective of Didion’s reportage is aided and transformed by her own involvement in the text.

I felt this way about some other essays in her collection, particularly whenever Didion’s essays showcased her love of things American and Californian: water, distribution, highways, the shopping mall, the Hoover Dam, etc. And yet, in other essays I felt her presence actually disrupted the story, or else that she felt too detached from her subject material. The brief section of The White Album called “Women” had this feeling for me. One essay critiques the second wave feminist movement. No movement is perfect or above critique, and some of Didion’s observations felt true to me, but I also felt that she was infantilizing the women she claims are infantilizing themselves, and she was giving in too much to her own biases, rather than seeing life as it was. Her other essays about the women Doris Lessing and Georgia O’Keeffe have a strange detachment to them, as though she’s afraid to show too much interest in her subjects, or else incapable of generating whatever excitement led her to write the piece.

So, New Journalism is a double-edged sword. Involve yourself in your subject material, and you can both frame the reader’s perspective in new and intimate ways, or you can alienate the reader by indulging in your own biases. It’s a tricky tightrope to walk. My advice to first-person essayists, if I have any, is to speak to yourself (and thus, your reader) without artifice. Radical sincerity is essential for bringing an authentic self and story to the reader. While there’s always an element of performance involved when a writer writes towards the reader, honest intentionality is much more important than any art or artifice.

Reading Elif Batuman’s The Possessed

I also recently read Elif Batuman’s essay collection The Possessed (2010), which I can’t recommend enough. These essays are more literary criticism than reportage, so they don’t fall under the realm of New Journalism, but Batuman brings herself into her lit crit in such a way that the skills of New Journalism feel present in the work.

Batuman is, to put it simply, incredibly intelligent, and also incredibly funny. She’s one of the few intellects I admire, and one of the few writers that makes me laugh out loud. On the surface, these essays are about her experiences as a Comparative Literature student specializing in Russian novels. Really, these essays explore what reading Russian literature revealed to Batuman about society and the human experience.

If you’ve ever felt intimidated by literary criticism, Batuman makes complex ideas easy to digest, though her work never shies away from complexity. In some essays, she writes about her experiences as a literary researcher, attending Russian Literature conferences, and visiting Yasnaya Polyana (Leo Tolstoy’s Russian estate). These essays are brilliant on their own, and instantly recognizable, in that the characters Batuman depicts are just as quirky as the writers and readers I’ve met at conferences. Other essays are about her time studying the Uzbek language in Samarkand.

But I was most moved by the essays that begin and end the collection. The opening essay, simply titled “Introduction,” rang true for me in unexpected ways. Batuman describes her experiences in undergrad, in which she became disillusioned with linguistics but fell in love with language and literature; and in which she knew she wanted to write a novel, but was disappointed by her experience in writing workshops. Namely, she notes that writing workshops divorce themselves from matters of literary theory and history. Instead, workshops contain a certain hermeticism, in which contemporary writers only converse with other contemporary writers. Those writers are then tasked with reducing complexity, with stifling bad writing habits, and with creating movie-like textual experiences, rather than explorations into humanity. What did a writing workshop have to offer if it seemed to avoid real life?

I’m aware of the irony here—I’m writing this essay for Writers.com, the creative writing school I help run.

And I could argue that Batuman’s observations are overly-cynical or cherry picked, not indicative of the writing world as a whole. I’ve certainly had experiences running and participating in workshops where real life felt magnified. And yet, Batuman’s essay felt true to me, and the more I considered it, the more I revisited the lessons my craft courses taught me, and which of those lessons were wrong.

Batuman’s concluding essay is her eponymous one, “The Possessed.” Here, literary theory and real life reflect each other like miracles. Batuman writes about how a literary critic, René Girard, developed a theory called “mimetic desire.” Girard argues that people tend to mimic the people they desire to be, and that all human personality is constructed of different mimeses in an attempt to be the people we’re not. It’s a dark theory, certainly open to criticism, but it helped Batuman come to two truths. First, it helped unlock Dostoevsky’s novel Demons which, if you’ve read it, you’ll know its plot is rather random and seemingly senseless. Second, it helped Batuman understand a crush she had on a fellow student in her graduate school, how everyone’s obsession with this student was a product of mimetic desire, and how that student himself was made inaccessible because of his own tortured relationship with desire.

I do a poor job of summarizing the essay, because it simply can’t be reproduced: Batuman’s expansive understanding of literature and life are on full display in this work, and she marries beauty and truth in her attempts to marry theory and reality.

I realize, after writing this, that Batuman and Didion left me with different conclusions. In Didion, I felt a reassurance about my own Nihilistic tendencies. In Batuman, I found respite from Nihilism, seeing how literature—not narrative, but literature—can make sense of real life and ascribe meaning to it. I finished Batuman’s collection with a newfound sense of my love for literature, and I’ll return to her writing if that love ever falters.

Marrying Literature and Life

Indeed, writing can feel divorced from everyday life. Even the work of creative nonfiction can feel divorced from its subject material. Didion’s essays, for example, don’t always reveal real life to me; conversely, the adage “truth is stranger than fiction” has always rang true. And then, of course, there’s the matter of artistic license: writers are allowed, perhaps even supposed, to deviate from reality in an effort to understand the world.

And it’s true that there are works of genre fiction, for example, that sometimes feel truer to me than nonfiction. Haruki Murakami’s surrealist novels reveal the depths of the psyche and the spiritual world. Alternately, The Twilight Zone is unsettling precisely because of how real those stories seem, how they strike at the heart of human psychology.

What’s a writer to do? What I pulled from reading Didion and Batuman is this: good writing doesn’t construct, deconstruct, or reconstruct life, it simply explores it.

What I mean is, the best works of literature are never trying to convince you of a certain reality. At most, they provide the necessary context to understand a particular reality—but they never feel like they’re scaffolding a world just to build a story inside of it. This is true, again, even for genre fiction writers: a story set in a spaceship or a wizard’s tower can still be true if I recognize real life inside of it.

Didion’s essays about women didn’t ring true for me, because they were trying to construct their subjects, rather than represent them as they were. Yet those essays in which she gives in to her love of California, or in which she gives in to her anti-narrative Nihilism, required only the simple truth to reach such profound and complex conclusions. Similarly, Batuman indulges in her love of literature, and real life comes out at the other end.

To live and write without artifice is a whole philosophy, easier said than done, but all writers ought to be tasked with it if they seek to write—and change—the world.