What is Freytag’s Pyramid, and how can it help you write better stories? In simple terms, Freytag’s Pyramid is a five-part map of dramatic structure itself. Understanding the five steps of Freytag’s Pyramid will give you a clearer sense of what makes a strong, compelling story.

Most stories follow a simple pattern called Freytag’s Pyramid.

Storytelling is one of the oldest human traditions, and although the art of creative writing traverses dozens of genres and thousands of languages, the actual storytelling formula hasn’t changed all that much. Whether you’re writing short stories, screenplays, nonfiction, or even some narrative poetry, the majority of stories follow a fairly simple pattern called Freytag’s Pyramid.

Introduction to Freytag’s Pyramid

What is Freytag’s Pyramid? Novelist Gustav Freytag developed this narrative pyramid in the 19th century, as a description of a structure fiction writers had used for millennia. It’s quite famous, so you may have heard it mentioned in an old English class, or maybe more recently in one of our online fiction writing courses.

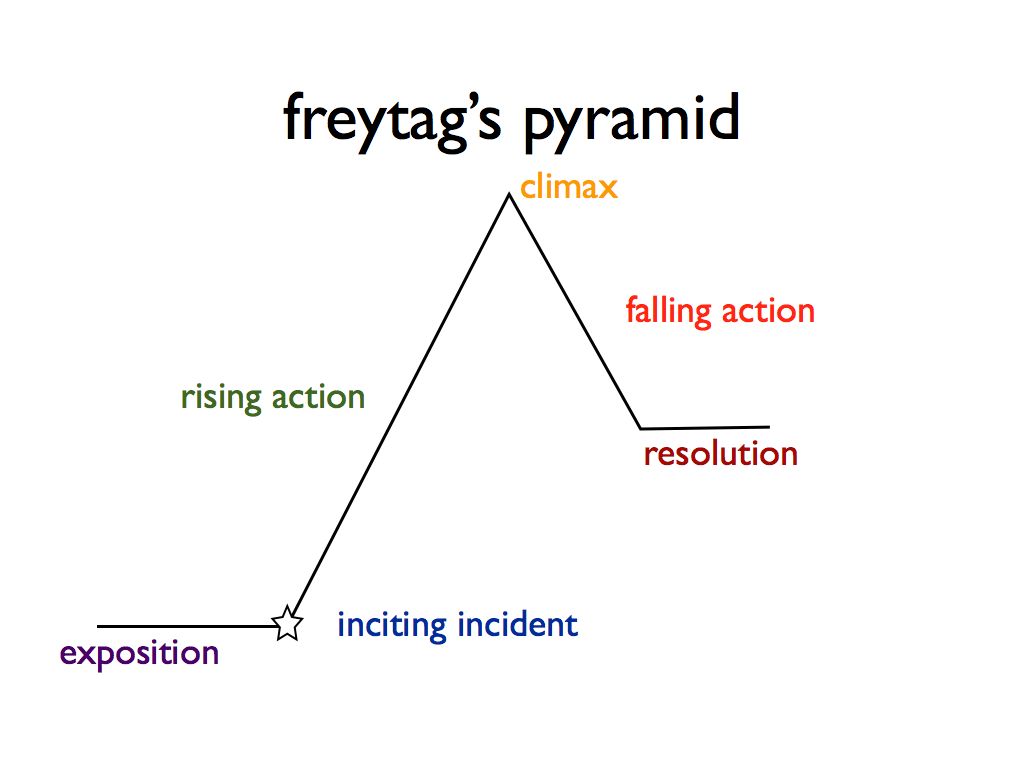

Freytag’s Pyramid describes the five key stages of a story, offering a conceptual framework for writing a story from start to finish. These stages are:

- Exposition

- Rising Action

- Climax

- Falling Action

- Resolution

Here is the five-part structure of Freytag’s Pyramid in diagram form.

Stages of a Story: Freytag’s Pyramid Diagram

If you’re looking to write your next story or polish one you just wrote, read more on Freytag’s Pyramid and what each element can do for your writing.

1. Freytag’s Pyramid: Exposition

Your story has to start somewhere, and in Freytag’s Pyramid, it starts with the exposition. This part of the story primarily introduces the major fictional elements – the setting, characters, style, etc. In the exposition, the writer’s sole focus is on building the world in which the story’s conflict happens.

The length of your exposition depends on the complexity of the story’s conflict, the extent of the world being written, and the writer’s own personal preference. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings is wrought with backstory and exposition, often spanning chapters of pure worldbuilding. By contrast, C. S. Lewis offers very little exposition in the Chronicles of Narnia series, choosing instead to entangle conflict with worldbuilding. Still, whether your exposition is fifty pages or a sentence, use this part of the story to draw readers in. Make your fictional world as real as this one.

Your exposition should end with the “inciting incident” – the event that starts the main conflict of the story.

2. Freytag’s Pyramid: Rising Action

The rising action explores the story’s conflict up until its climax. Often, things “get worse” in this part of the story: someone makes a wrong decision, the antagonist hurts the protagonist, new characters further complicate the plot, etc.

For many stories, rising action takes up the most amount of pages. However, while this part of the book explores the story’s conflict and complications, the rising action should investigate much more than just the story’s plot. In rising action, the reader often gains access to key pieces of backstory. As the conflict unfolds, the reader should learn more about the characters’ motives, the world of the story, the themes being explored, and you may want to foreshadow the climax as well.

Finally, when you look back at the story’s rising action, it should be clear how each plot point connects to the story’s climax and aftermath. But first, let’s write the climax.

3. Freytag’s Pyramid: Climax

Of course, every part of your story is important, but if there’s one part where you really want to stick the landing, it’s the climax. Here, the story’s conflict peaks and we learn the fate of the main characters. A lot of writers enter the climax of their story believing that it needs to be short, fast, and action-packed. While some stories might require this style of climax, there’s no strict formula when it comes to climax writing. Think of the climax as the “turning” point in the story – the central conflict is addressed in a way that cannot be undone.

Whether the climax is only one scene or several chapters is up to you, but remember that your climax isn’t just the turning point in the story’s plot structure, but also its themes and ideas. This is your opportunity to comment on whatever concept is driving your story’s narrative, giving the reader an emotional takeaway.

Note: for playwrights, the climax is usually the middle act, though of course not every theatrical production follows the rules.

4. Freytag’s Pyramid: Falling Action

In falling action, the writer explores the aftermath of the climax. Do other conflicts arise as a result? How does the climax comment on the story’s central themes? How do the characters react to the irreversible changes made by the climax?

The story’s falling action is often the trickiest part to write. The writer must start to tie up loose ends from the main conflict, explore broader concepts and themes, and push the story towards some form of a resolution while still keeping the focus on the climax and its aftermath. If the rising action pushes the story away from “normal,” the falling action is a return to a “new normal,” though rising and falling action look dramatically different.

At the same time, the story must still engage the reader. When writing the story’s falling action, be sure to expand on the world of the story, the mysteries that lie within that world, and whatever else makes your story compelling.

5. Freytag’s Pyramid: Resolution/Denouement

How do you end a story? One of the most frustrating parts of writing is figuring out where the narrative ends. Theoretically, the story can continue on forever, especially in the aftermath of a life-altering climax, or even if the story is set in an alternate world.

The resolution of the story involves tying up the loose ends of the climax and falling action. Sometimes, this means following the story’s aftermath to a chilling conclusion—the protagonist dies, the antagonist escapes, a fatal mistake has fatal consequences, etc. Other times, the resolution ends on a lighter note. Maybe the protagonist learns from their mistakes, starts a new life, or else forgives and rectifies whatever incited the story’s conflict. Either way, use the resolution to continue your thoughts on the story’s themes, and give the reader something to think about after the last word is read.

Some writers also use the term “denouement” when discussing the resolution. A denouement [day-new-mawn] refers to the last event that ties up the story’s loose ends, sometimes expressed in the story’s epilogue or closing scene.

Closing Thoughts on Dramatic Structure

Though some literary works break the traditional narrative structure of Freytag’s Pyramid or try to invert it, every story has a relationship to these five dramatic elements. Having a dramatic structure is the first step to a full story outline, which is especially important for longer works of fiction—especially writing the novel. Once you’ve fine-tuned these parts of the story, you’ll have written your next creative work from start to finish!

Hello. I am trying to be a playwright. I have written several plays and have a great Mentor, a professional playwright herself. However, she has confused me recently and I wonder if you can settle the issue. When I first started writing she recommended Michael Hauge’s Six Stage Plot Structure. I have been using this to structure my plays. She has recently suggested Freytag’s Pyramid. My confusion is where does the climax come in. Freytag has it in the middle. Hauge clearly has it at Stage V about 90% into the play.

How do I resolve this structure issue?

Hey Ed, great question! It comes down to a difference in philosophies about story structure. Freytag’s structure is heavily influenced by an admiration for Greek plays, which valued symmetry and thought that a climax ought to be in the middle. Some playwrights, like Henrik Ibsen, subscribed to this notion very intensely.

Hauge, as you mentioned, puts the climax way later, which is a more modern idea of the climax – the idea that climax and resolution go hand-in-hand, and also that climax should provide a certain level of entertainment and suspense.

I think your question is best answered by what you’re trying to accomplish. If you’re looking for symmetry, choose Freytag; if you’re looking for suspense or modernity, choose Hauge.

I thought this story structure originally came from Aristotle?

Hi Becky! You’re right in a way. Aristotle originally mapped a story triangle in his Poetics, based on his observations of Greek literature. However, his triangle only included (in translation) the Exposition, Climax, and Resolution. Freytag adapted this triangle and added two more sections–the Rising Action and the Denouement. These structures have existed far before even Aristotle’s time, we just credit Aristotle and Freytag for observing and mapping those structures. Thanks for your comment!

Thanks so much for clarifying so many issues.

I am writing a true story of which I am part, but with multiple characters. My struggle has been writing from first person point of view or third person. In the process of searching, I landed on this page and what a blessing. You have explained more and helped me understand writing a story using Freytag’s Pyramid. My online course explained it in fundamentals of fiction and memoir writing using; the set up, inciting incident, first slap, second slap ( I think), climax and then resolution, but herein, I get a better picture I believe. Thanks so much. If you have any suggestions on which point of view to use in a story I am involved in with other characters, please let me know. Thanks again.

Hi Victoria,

I’m so glad this article was helpful! We have another article related to point of view that may interest you, check it out here.

Best of luck writing your story!

[…] Why four? Well, originally it was because I figured that the Falling Action and Resolution from Freytag’s Pyramid could be combined; both are usually relatively short in novels (and just about anything that […]

[…] you can follow. There’s the synopsis outline, the snowflake method, the Hero’s Journey, Freytag model, or the three-act structure, among many others. My personal favorite is the three-act structure […]

[…] plot structure to use in narrative fiction: some people swear by a standard three-act, some find Freytag’s Pyramid useful, you’ve probably heard about “the hero’s journey” a million times. They all tend to […]

[…] if a story has a long resolution in terms of the Freytag plot triangle, it is a sign that the author is (1) signaling a sense of long-term stability, indicating the […]

[…] movies is nothing new, often citing the studios frequent use of the Hero’s Journey and Freytag’s Pyramid theories of narrative structure. Even veteran Hollywood director Martin Scorsese had something to […]

[…] of fiction: plot, character, setting, theme, and structure. “Night Train” fits into Freytag’s plot triangle although many of the segments are very […]

[…] (2020) The 5 Stages of Freytag’s Pyramid: Introduction to Dramatic Structure. Available at: https://writers.com/freytags-pyramid (Accessed: 15th April […]

“When he’s not writing, which is often, he thinks he should be writing.” Haha, that is totally me! I am teaching my students personal narratives and am using Freytag’s Pyramid to help them craft their stories. Additionally, I hope they connect the theory to a “growth mindset” too.

Thank you for giving us a contemporary take on the story shape.

[…] Stories are often lovable because of the troubles and trials you watch and overcome together with the protagonist. Why else would most stories would follow Freytag’s pyramid structure? […]